Animated by an Independent Spirit

The error is here, not here…

We may be the last generation of Americans to whom the words “coonskin cap” immediately conjure up the image of a leather clad man wildly swinging his musket in a desperate last stand. That man, Davy Crockett, “king of the wild frontier,” may soon be forgotten.

To previous generations, and any good student of American history, however, the name Davy Crockett remains alive and well. His Disney-fied persona that awed an entire generation in the 1950s was derived from myths and folklore surrounding his life a century before. The man who fought bears, told his own constituents to “go to hell,” and met his fate at the Alamo defined much of the “rugged individualism” that Americans still crave.

Like it or not, Crockett’s legendary life helped shape both the nobler and the darker sides of the American conscience. And similar to many historical giants, Crockett is a complex, sometimes contradictory figure. Yet in peeling away the myths and folklore about him, we must remember that he lived in a time marred by the spread of slavery. It will not surprise Americans today that as a Tennessean and Southerner, Crockett owned enslaved people; at least two, according to the 1830 census.

Many today also may not realize that thousands of slaveholding Americans fought in the Texas Revolution. After telling his constituents to “go to hell,” Crockett made for Texas, where he joined other slaveholders like the commanders of the Alamo, William B. Travis and James Bowie in the war for Texan Independence. They and 200 “Texians” died defending the Alamo against the forces of Mexican Emperor Antonio López de Santa Anna, whose government banned slavery. Therefore, while the Battle of the Alamo is remembered as a symbol of Texan independence, story of self-sacrifice, and frequently depicted in a series of Hollywood epics, the fort’s commanders and many of its defenders fought for the right to enslave people.

| William B. Travis, James Bowie, Antonio López de Santa Anna |

Despite his imperfections Davy Crockett still deserves a place in the American pantheon. He embodies an indomitable American spirit and fierce commitment to conscience while pursuing American ideals. The struggle for equality began through American independence and ushered in a new way of being, one contingent upon what individuals could make of themselves and how individuals could rise above their limitations. Crockett’s life as well as his conscience exemplify the progress toward realizing America’s ideals.

Replica of Crockett’s cabin at David Crockett Birthplace State Park Limestone, Tennessee

Born in the state of Franklin, now eastern Tennessee on August 17th, 1786, Crockett endured a hardscrabble childhood. Never attending school for more than “six months” by his estimate, Crockett hunted, trapped, and worked as a wagoner and day-laborer throughout his teenage years. He left home at 20, married, and after living in the mountains of eastern Tennessee for five years, finally settled with his family in western Tennessee in 1811.

Two-years later Crockett began his military career in 1813, serving under General Andrew Jackson in the Creek War, which pit the Lower Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, and their US allies against the Red Stick Creek, backed by Great Britain and Spain. The conflict began in Florida, then a Spanish possession, and soon expanded, drawing the US into war to support their Indigenous allies, many of whom participated in the fledgling American economy and had adopted the cultural practices of American settlers.

In August 1813, Red Stick warriors attacked and massacred over 400 men, women, and children, both white and mixed-blood Creek, at Fort Mims in present-day Alabama, stoking American outrage. In November 1813, Crockett witnessed and took part in a “retributive” attack on the Red Stick town of Tallushatchee.

A sketch of a Chickasaw warrior by Bernard Romans, ca. 1775

Chief Kutteeotubbee of the Choctaw, a noted warrior, ca. 1834

Crockett held complicated views of Indigenous people that spoke to his lived experience of the frontier. Put simply, Crockett divided them into two groups: “troublesome” and “friendly.” Examples of the first group included the Creek and Cherokee warriors who murdered his grandfather and grandmother, wounded one uncle, and kidnapped another uncle. At Talluschatchee, Crockett later wrote, he and his fellow soldiers shot Red Sticks “like dogs” before setting ablaze a house in which 46 braves and their families were hiding. To Crockett, “friendly” meant helpful, but certainly not harmless. After all, the same Indigenous people who hunted with him, scouted with him, and even saved his life were the same people, in this case, the Chickasaw and Choctaw, who fought alongside him during the Creek War.

David Crockett by John Neagle, 1834

The next two decades cemented Crockett’s place in American history and folklore. He continued his military career, eventually being elected colonel of the 57th Tennessee militia. Though a failure in business, he found great success as a hunter, claiming to have shot over 100 bears in a single winter. In 1821, Crockett ran for and won a seat in the Tennessee state legislature, which enabled him to develop his folksy wit and memorable anecdotes. Slowly becoming a larger-than-life figure, Crockett ran for Congress and won in 1827, representing west Tennessee’s rural 9th district in the House of Representatives.

Crockett considered public land policy, especially squatters’ rights, as the backbone of his political work. Composed from land ceded by the Chickasaw, the 9th district experienced a population explosion in the 1820s due to an influx of squatters, planters, speculators, and enslaved people. Although Crockett would not live to see it, his district would soon become part of the largest cotton kingdom in the state, with enslaved people representing 40% of the population by 1860.

Like Andrew Jackson, whom he initially supported, Crockett’s political success flourished because he was a frontiersman and slaveholder who spoke for the common man. Yet unlike Jackson’s admirers, Crockett would not be seduced by plans that forced squatters out of Tennessee. He railed against banks and speculators who poured into western Tennessee to “speculate upon the labor of the poor,” and drive these “sons of the soil” from their homes. Instead, Crockett proposed giving squatters 100-acres if they had lived on the land the previous year.

Jackson supporters labelled him a troublemaker, and Crockett realigned himself with the anti-Jacksonites that would become the Whig Party.

And it was Crockett’s support of another group that sealed his political fate: the Indigenous people living in his district, all of whom Jackson and his allies marked for removal in 1830. The Indian Removal Act considered five major tribal nations, the Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole as “troublesome,” grouping them together as a singular threat to settlement and the expansion of slavery’s cotton kingdom.

Map of the route of the Trails of Tears — depicting the route taken to relocate Native Americans from the Southeastern United States between 1836 and 1839

Crockett’s ability to view Indigenous people as human beings set him apart from most of his contemporaries. He delivered a speech to the House of Representatives on May 19, 1830, in which he explained that his conscience demanded his honesty, respect, and honor toward Indigenous nations. Crockett feared that the Act, combined with a lack of Congressional oversight, would lead to a miserable fate for the five tribes. Crockett knew many Chickasaws, and “nothing should ever induce him to vote to drive them west of the Mississippi.” And while he might suffer the abuse of Democrats and his Tennessee constituents, he would vote against removal with a “clear conscience.” Expulsion would be as “oppression with a vengeance.”

In closing,

He had been charged with not representing his constituents. If the fact was so, the error is here (touching his head) not here (laying his hand upon his heart). He never had possessed wealth or education, but he had ever been animated by an independent spirit; and he trusted to prove it on the present occasion.

This “wicked, unjust measure” to forcibly evict human beings ran counter to the fundamental qualities of “honesty and right” that drove his character, whether political, mythical, or otherwise. Crockett’s independent spirit and conscience reinforced each other, for in his words, “I would rather be honestly and politically damned, than hypocritically immortalized.” His words challenge Americans to do the right thing when confronted by injustice and oppression.

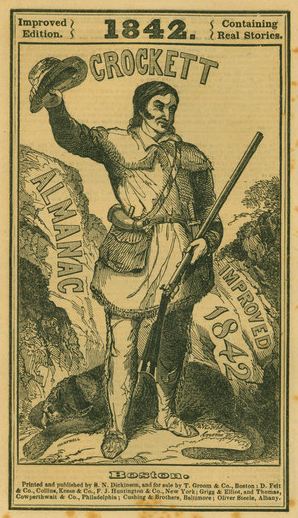

In the short term, Crockett’s constituents “damned” him by promptly voting him out of office in 1831. From there, his political successes waned while his mythology grew. A national folk hero even prior to the famous Battle of the Alamo, he inspired the imagination and consciences of countless Americans through tales, books, almanacs, comics, and even stage productions about his fascinating life.

His wish would become a reality, for whether we realize it or not, Americans have immortalized Davy Crockett in a way through their persistent ability to follow their consciences to do what is right and honest. Despite his shortcomings and trappings of his time, Americans can still appreciate the “blunt integrity and frank independence” of Davy Crockett, “an unlettered son of the forest.”

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).

Enjoyed this piece? Sign up for our newsletter to read more stories from American history!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.

![]()

![]() Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.