Our moral lights

The right to eat the bread – thinking about why Lincoln was “most pleased” with his debate with Douglas at Ottawa.

“I was better pleased with myself at Ottawa than at any other place.“

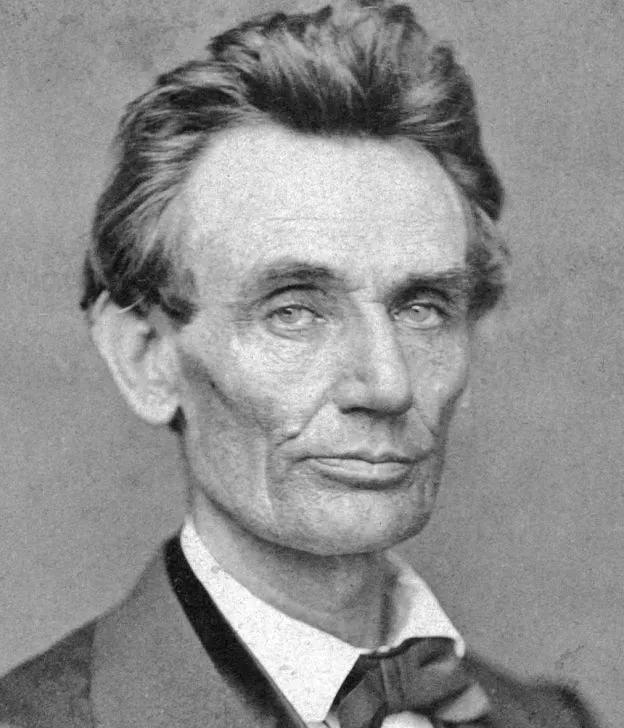

This week we celebrate the 164th anniversary of the first Lincoln-Douglas debate. It marked the beginning of a series of seven prominent debates between Republican Abraham Lincoln and Democrat Stephen Douglas.

Meeting across Illinois, the two men sparred over a seat in the United States Senate. In the process, they examined some of the most important issues in American history: the institution of slavery, the founding, and the Declaration of Independence.

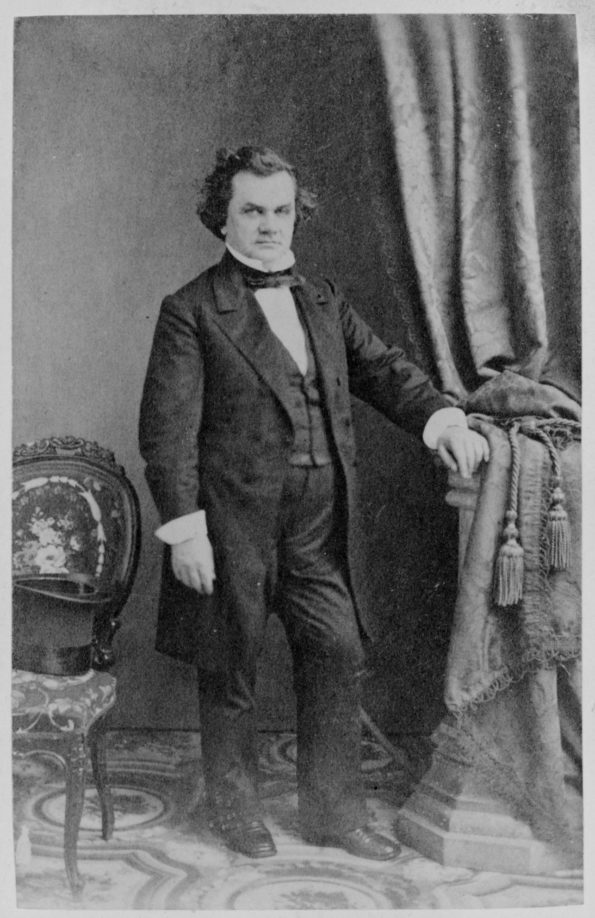

The debates keyed in on the public’s growing concerns over the expansion of slavery. A staunch Democrat who enjoyed national fame, the incumbent Senator Douglas espoused the doctrine of “popular sovereignty.” In other words, Douglas believed that the sovereignty of the people ought to decide whether slavery could exist in new lands acquired by the United States. The doctrine had already been put to the test with the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act. As a result, pro and anti-slavery setters mobbed the territory with the intent of voting to make the state open or closed to slavery.

Lincoln saw popular sovereignty as a recipe for disaster. In fact, the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and subsequent violence of “Bleeding Kansas” roused Lincoln from political slumber. He railed against the Act because it repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which forbid the spread of slavery north of the 36º 30’ parallel. Three years after the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed, in the infamous Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court ruled the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional: in essence, Congress could not ban slavery from the territories. The polarizing nature of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Dred Scott decision, and the wayward course of the country moved Lincoln to make his “House Divided” speech shortly before meeting Douglas for their first debate in Ottawa, Illinois on August 21, 1858.

Ottawa, a small canal town and the seat of LaSalle County, exploded as a wave of perhaps 20,000 spectators gathered for the debate. Although the town leaned Democratic, enough Republican stalwarts flooded the town, making the crowd pretty evenly divided by political party. This “vast concourse of people” went to Ottawa for two primary reasons. Firstly, debates were nothing short of entertainment: debaters were celebrities, and, the debates featured food, liquor, vendors, and music. Add in the scorching summer heat, raucous partisan fistfights, obnoxious hecklers, and rambunctious young men crowding (and even climbing) the debate stage, and one begins to understand the minor chaos and thrilling pageantry of 19th century politics. All these things (and more) were happening prior to the debaters even uttering a word!

Secondly, and more importantly, people went to the Lincoln-Douglas debate for a more practical reason: civil war loomed, and ordinary Americans knew that the meaning and fate of the Union were at stake.

Douglas’ strategy in this first debate was to put Lincoln on the defensive. He opened with a barrage of questions and issued several charges, each one intended to mischaracterize Lincoln and the founders. Douglas claimed that Lincoln was a “Black Republican” abolitionist who wanted to “abolitionize” the political system. According to Douglas, the founders “intended that our institutions should differ” and thought they might not use the precise term, supported popular sovereignty. Unlike the founders, Lincoln wanted “uniformity” across the country on the question of slavery. Douglas cast Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech as a subversive plot to make the entire country free, irrespective of local “peculiar” institutions like Southern slavery. Finally, Douglas charged Lincoln with believing that all men, including Black men, were created equal:

[Lincoln and abolitionists] maintain that negro equality is guaranteed by the laws of God, and that it is asserted in the Declaration of Independence.

In short, Douglas argued that Lincoln sought to undermine slavery and the founder’s intentions to promote healthy differences in the nation by creating a uniform equality between all Americans, regardless of race.

Lincoln spent much of his response answering Douglas’ questions and defending himself. His initial reactions provided grist for Democratic journalists in attendance, who later claimed that Lincoln dodged questions and appeared embarrassed by Douglas’ electrifying performance. Even modern historians admit that some of Lincoln’s replies feel as though “he had thought out nothing of his own to say.”

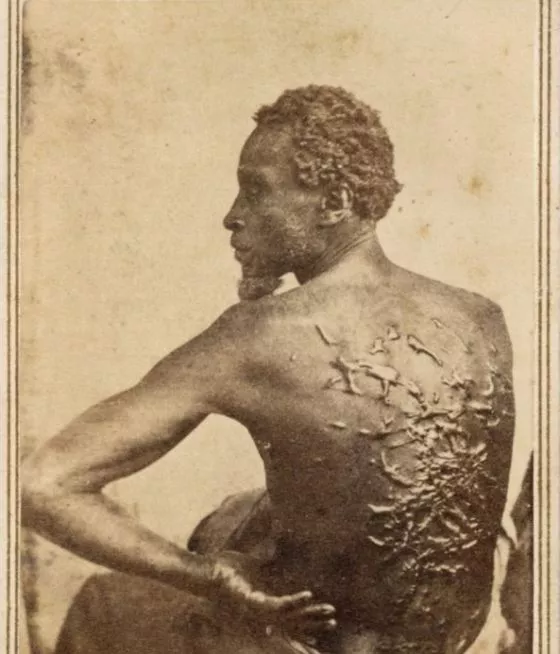

The monstrous injustice of slavery

Under close inspection, Lincoln’s defensive rhetoric hints at why this debate made him so “pleased with himself.”

Lincoln showed empathy in confessing that though he hated the “monstrous injustice of slavery,” white Southerners were “just what we would be in their situation.”

He then expanded this deep sense of empathy to another group of Southerners: enslaved Blacks.

While considering the end of slavery, Lincoln traced a remarkable argument premised upon both pragmatism and freedom.

His first impulse was to free all enslaved people and send them to Liberia. But this was impracticable because many freed people would die within the first week, Lincoln averred.

What then? Free all enslaved people, but retain their “underling” status? No, that would not make their condition any better, Lincoln asserted.

What next? Free all enslaved people, and make them politically and socially, our equals? Even if his own feelings would prescribe this solution, Lincoln said, “the great mass of white people will not.”

Systems of gradual emancipation to free all enslaved people may be too little, too late, and ultimately too unpalatable to the South, he explained.

Note how each one of his solutions would free all enslaved people in some way.

Lincoln gave these options to introduce what he believed was the crux of the founding and the Union itself: “all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Despite the diversity of institutions in the nation, the founders did not intend for popular sovereignty to invalidate natural rights guaranteed by the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln appealed to the greatest fundament of liberty: human equality. Black Americans, like all Americans, possessed “the right to eat the bread, without leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, [and] he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man.”

Douglas’ doctrine of popular sovereignty meant indifference to slavery and equality because it disavowed the founders, ignored the Declaration of Independence, and blew out the “moral lights” of liberty.

Lincoln and Douglas would spar another six times before the election, an election that Douglas would win. They would face each other again in the 1860 Presidential election, an election that Lincoln would win.

Lincoln’s “oft-expressed personal wish” for human freedom carried him through the debates with Douglas and found their fullest expression in his actions as President. He effectively “abolitionized” the country by laying the groundwork for freedom in the Emancipation Proclamation and ending slavery through the 13th Amendment. His future actions may be glimpsed in his words in the debate with Douglas in Ottawa. He was “better pleased” with himself there not because of political gamesmanship, but perhaps because his words expressed deep-seated truths about equality and liberty that only the founding ideals of the United States of America could make manifest.

This post was also featured on RealClear History.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).