Women Holding Self-Evident Truths

This week marks the 174th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention, a landmark event in our historical journey to realize the promises of the Declaration of Independence.

What were the origins of this convention, and what made the convention such a pivotal moment in American history?

Two humiliated women walked arm-in-arm through London on a warm summer night in 1840. Mere hours earlier, these women – Lucretia Mott (left) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (right) – faced the wrath of many of their male abolitionist counterparts who denied them from participating at all at London’s World Anti-Slavery Convention.

“The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840,” by Benjamin R. Haydon (1841) depicts members of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. Mott and Stanton are featured on the right.

While some abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison believed that female abolitionists deserved an equal chance to participate, many viewed women like Mott and Stanton as agitators. And although many women served as zealous abolitionists throughout the United States, these men believed that giving women a voice at the convention might weaken the abolitionist cause.

After all, these men argued, women like Mott and Stanton might have more ambitious aims for equality, such as being granted the right to vote!

Mott and Stanton’s embarrassment led to a convention of their own eight-years later at Seneca Falls, New York.

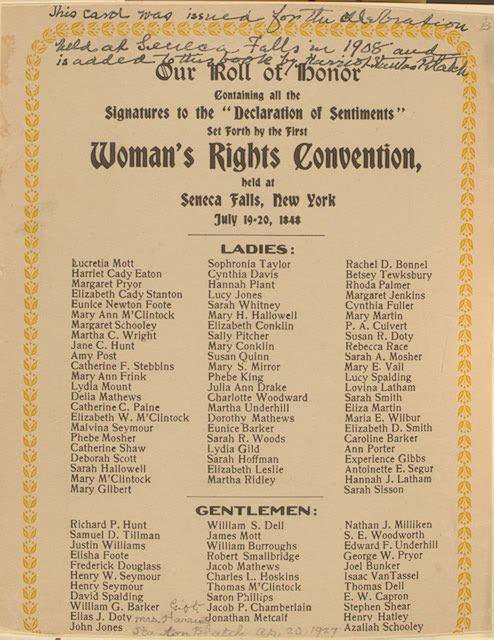

On July 19th, 1848, Mott, Stanton, and over 200 women met and read a treatise drafted by Stanton. Entitled “The Declaration of Rights and Sentiments,” this document borrowed and even modified the language of equality from the Declaration of Independence. Stating “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal,” the Declaration demanded the equality of the sexes and encouraged women to become active forces in the campaign for equal rights.

The document then listed the injustices suffered by women across the United States, the most important of which the denial of “her inalienable right to the elective franchise.”

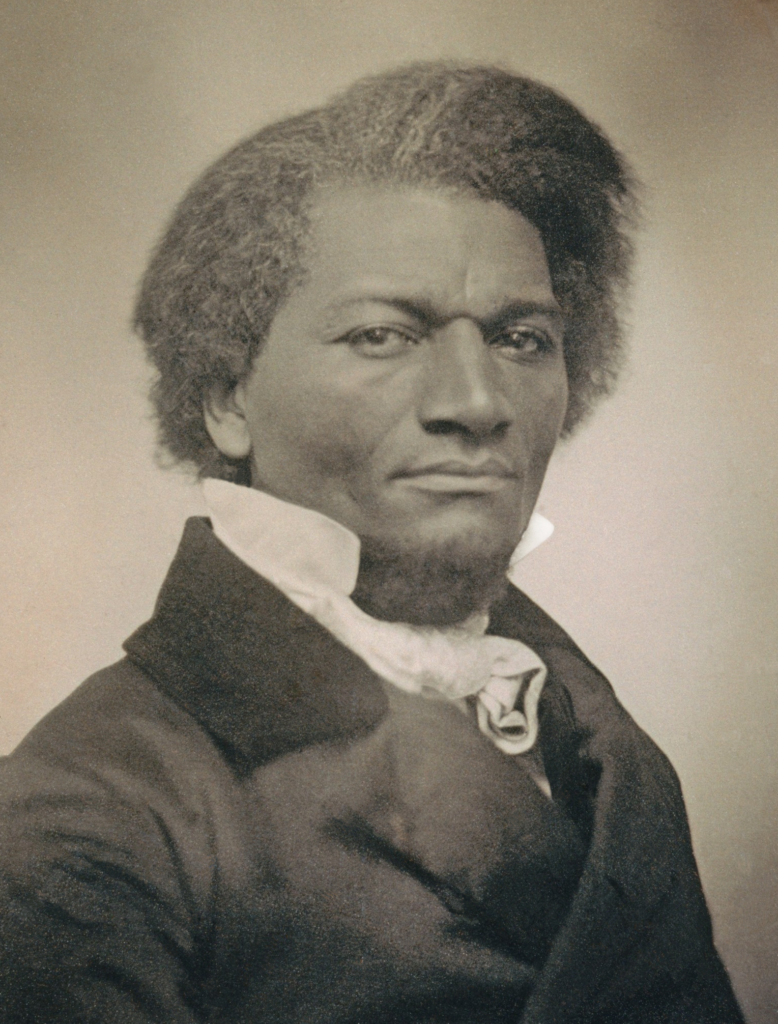

The ninth resolution, “that it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise,” met with controversy from some of the attendees, who viewed such a demand as unreasonable at best, quixotic at worst. The debate over this resolution reached its climax when none other than the African American leader Frederick Douglass sided with Stanton.

We have a sense of Douglass’ eloquent words he used in support women’s equality and suffrage in an article he wrote in his newspaper The North Star two weeks later:

Standing as we do upon the watch-tower of human freedom, we cannot be deterred from an expression of our appropriation of any movement, however humble, to improve and elevate the character and condition of any members of the human family […] and if that government is only just which governs by the free consent of the governed, there can be no reason in the world for denying to woman the exercise of the elective franchise…

The resolution for securing the right to vote soon became the foundation of the women’s rights movement in the United States.

While some western states, including Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and Idaho, allowed women’s suffrage in the decades following the convention, most of the United States restricted women from voting prior to the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. However, women at the Seneca Falls Convention helped make voting rights “self-evident” by showing all Americans how governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

Our mission at the Jack Miller Center is to educate young Americans about the freedoms given to us through our founding principles. The actions of women like Mott and Stanton represent moments in American history when the pursuit of those founding principles brought all Americans closer to realizing the vision from the Declaration of Independence, that all men and women are created equal.

This post was also featured on RealClear History.

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.

Relevant readings from JMC fellows & faculty partners

![]()

![]() Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.