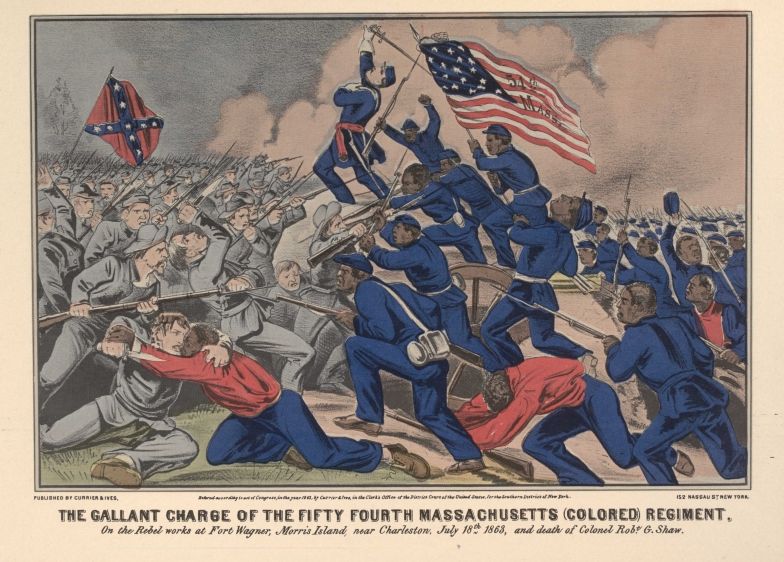

The hero of Fort Wagner

Uncovering the valor of one of America’s greatest heroes, Sgt. William H. Carney of the 54th Massachusetts. William Carney heard a familiar voice roar, “Forward 54th!”

You shall reap a great reward

Dashing up the steep slope with sand chafing his arms, legs, and neck, he saw a bullet-ridden flag flutter, beginning an agonizing plummet to the ground.

He must save the colors; he must save the colors. Throwing his rifle aside, he grabbed the Stars and Stripes before they landed on the gritty crest. Time stopped as he raised the flag. As a monstrous rifle volley “melted away” the soldiers around him, he felt the heat of a lead ball careen through his thigh. Carney braced himself against the flag, ready to die while rallying his friends to take the fort.

Despite the danger around him, Sergeant William H. Carney of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment survived, holding the flag aloft for one whole half-hour on Fort Wagner’s parapet.

William Harvey Carney was born enslaved in Norfolk, Virginia on February 29th, 1840. While his mother Ann was freed by her owner upon his death, his father William Sr. remained enslaved to Sarah Twine of Old Point Comfort, Virginia. Twine promised to free her slaves in her will, but when she died in 1857, the High Sheriff took them all to the auction block.

William Sr. escaped, making his way north via the Underground Railroad. He met with the indefatigable “conductor” William Still(left) in Philadelphia but still did not feel “secure on the soil where the Declaration of Independence was written.” Slavecatchers prowled the Philadelphia region, forcing the elder Carney to move to New York, though that city also had ruthless kidnapping gangs. Like Frederick Douglass, William Sr. finally found safety in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he worked as a skilled laborer and coastal sailor, and earned enough to emancipate the rest of his enslaved family.

Though not much is known of the younger Carney’s childhood, he later told a reporter that he attended a “private and secret school” led by a Norfolk minister who taught him how to read and write. Carney embraced the Gospel, and when he arrived in New Bedford as a young man, joined a church led by Reverend William Jackson, an Underground Railroad Agent who would not only become the chaplain of the 54th Massachusetts, but also the first Black man to be commissioned as an officer in the United States Army! Despite Carney’s “strong inclination” to join the ministry, the tug of the war inspired him to “serve my God by serving my country and my oppressed brothers” and so he enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts in February 1863.

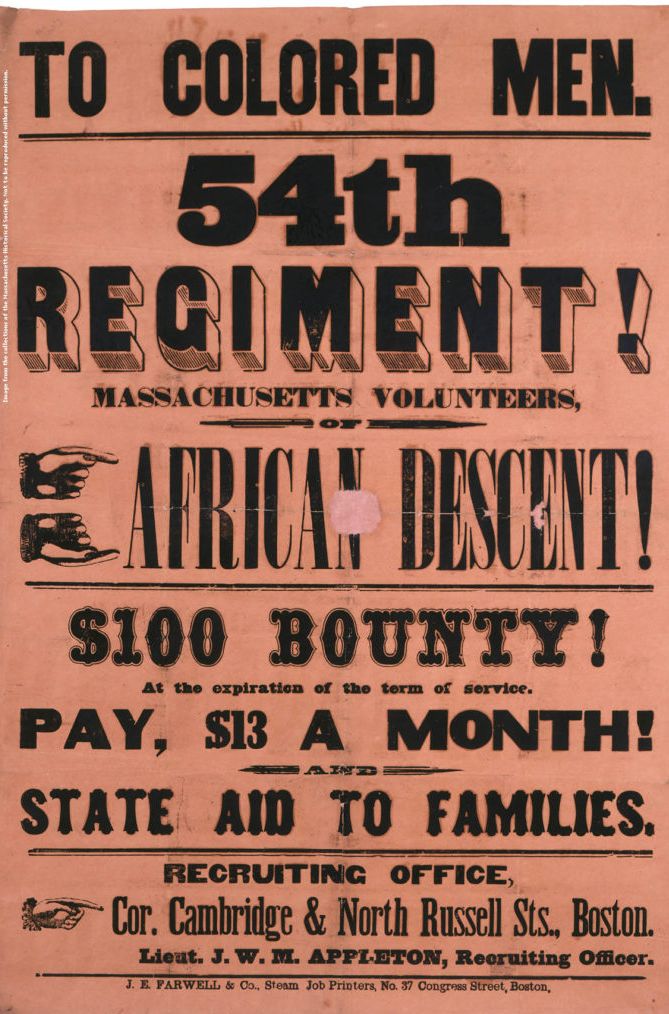

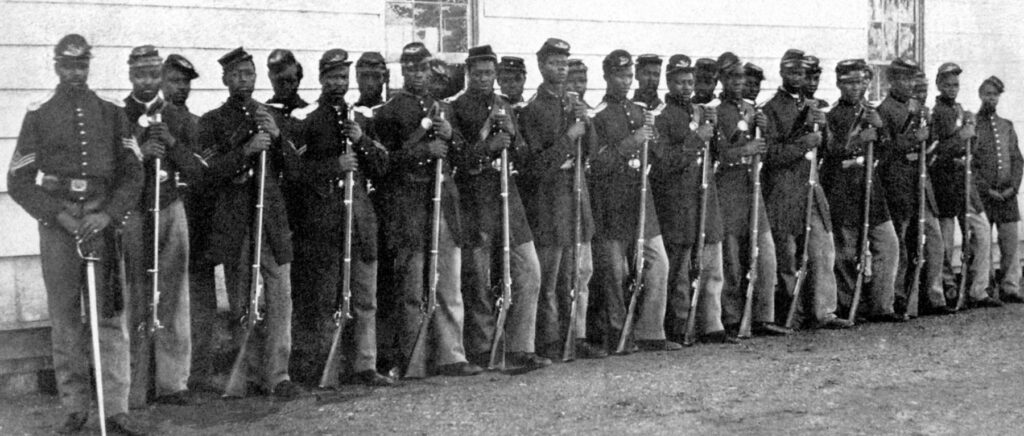

President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, had already announced that Black men could and would enlist in the United States Army and Navy. Many white Americans doubted their ability to fight, though by war’s end, over 180,000 Black soldiers and sailors had joined the Union cause. Their statistics were mindboggling: approximately three-quarters of military-age Northern Black men served. About half of them were former enslaved people from the Confederate States. 40,000 Black men lost their lives during the war. When Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew called for recruits, over 1,000 Black men responded, including two of Frederick Douglass’ sons, with many of these volunteers coming from the South and locales as distant as the Caribbean.

Though Andrew hoped to commission Black officers for this new regiment, the 54th Massachusetts, many viewed such a move as controversial, and therefore white officers led the Black recruits. The governor selected the 25-year-old Colonel Robert Gould Shaw to command the 54th. Born to a well-heeled Boston abolitionist family, Shaw was deeply moved by family friend Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and though initially reluctant to take command of the 54th, he soon greatly respected the eager Black recruits. Later, Shaw refused wages until his soldiers earned equal pay.

He drilled his regiment outside of Boston, and on May 28th, 1863, they paraded through the city to bid the residents farewell. The parade passed the home of the famous abolitionist Wendell Phillip, where William Lloyd Garrison watched them, crying with pride. Spectators thronged the streets of Boston, cheering the men on. At night, they left for the coast of South Carolina.

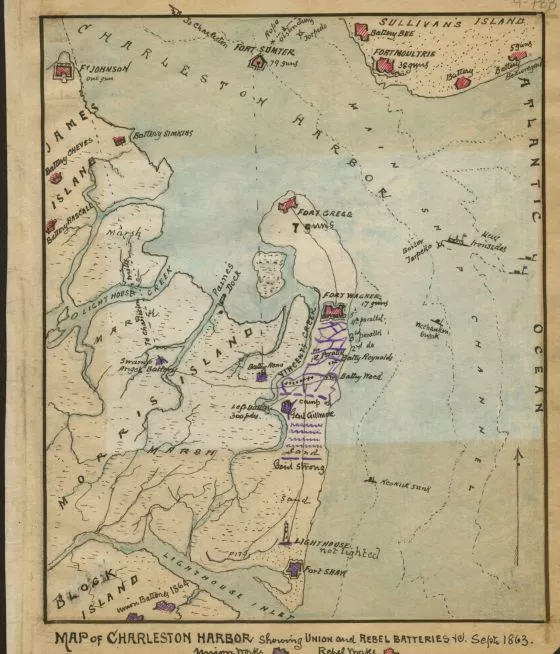

A strategic necessity

Fast-forward to early July 1863, when Union forces began the siege of Charleston, the city that many Northerners blamed for starting the Civil War. The (in)famous Fort Sumter loomed at the mouth of the city’s harbor and Fort Wagner, situated on Morris Island, guarded the southern part of the harbor. Understanding the strategic necessity and morale boost of capturing Charleston, Union commanders soon concocted a plan: Union forces would attack Morris Island from the south, take Fort Wagner, and then seize a battery on the northern tip of the island known as Cumming’s Point. The capture of Cumming’s Point would give the Union Navy the opportunity to level Fort Sumter and enter the port unmolested.

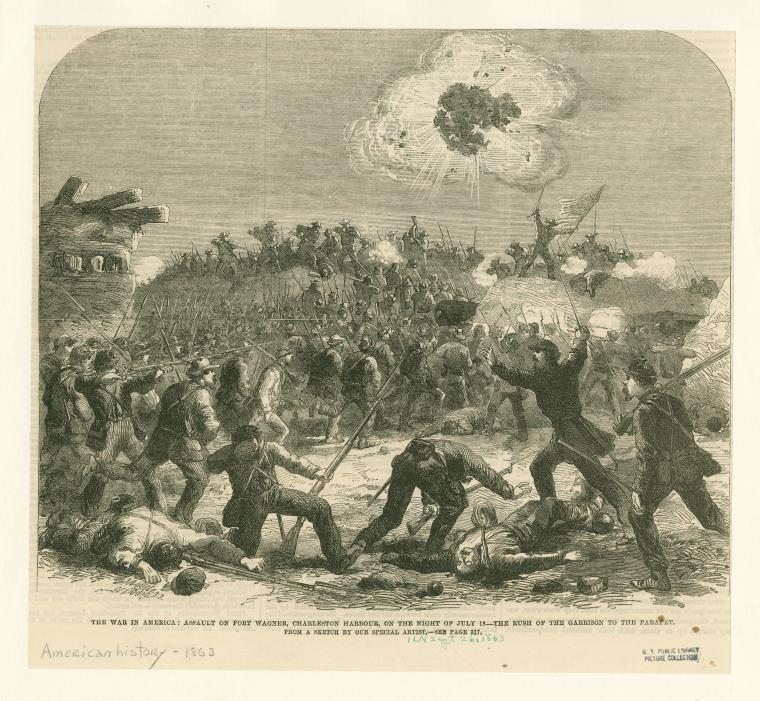

On July 10th, Union forces captured the southern tip of Morris Island but the next day, Confederate forces prevented the taking of Fort Wagner. The fort itself boasted 14 cannons, a massive bomb shelter for 1,000 of the fort’s 1,700 defenders, and a moat 10 feet wide and 5 feet deep. The Confederate forces stationed there prepared themselves for the next Union attack, which began with an 11-hour artillery barrage on July 18th. This bombardment was ineffectual, and the Confederates suffered few casualties. When the call was made for Union ground forces to take the fort at dusk on July 18th, the 54th Massachusetts led the way.

One veteran of the battle described the beach in front of Fort Wagner as “the fiery vortex of hell.”

The regiment surged through one of the narrowest points on the beach, effectively becoming a spear-shaped mass of men with Colonel Shaw and the flagbearer at the tip. Running over the dunes, wading through the moat, and now scaling the sandy ramparts, they watched as Shaw raised his sword atop the fort’s parapet crying “Forward 54th!” and met his death in a hail of gunfire.

Carney did not wait to act after Shaw fell. He recovered the flag, held a futile rallying point on the sandy crest of the fort, and two hours later, limped back to the field hospital. He refused to let anyone take the flag from him, and before he fainted from blood loss, told the men around him, “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground!”

The Union forces failed to take Fort Wagner that day. The 54th Massachusetts suffered heavy losses during the battle, and many of the survivors captured by the Confederates were given no quarter or sold into slavery. Shaw’s body was tossed into a mass grave alongside the brave Black Americans who fought and died with him. Those wounded in the battle evacuated to Beaufort, South Carolina the next day. According to The Free South, a Beaufort newspaper:

The wounded of the 54th Massachusetts came off the boat first, and as these sad evidences of the bravery and patriotism of the colored man passed through the lines of spectators every heart seemed to be touched, and we will vouch for it that no word of scorn or contempt for [Black] soldiers will ever be heard from any who witnessed the sight. In that moment our volunteers saw suffering comrades in the black men, and the tender hand and strong shoulder was extended as readily to them as to their fairer compatriots.

Nobody embodied “bravery and patriotism” more than Sergeant William H. Carney, an American whose wartime efforts epitomized the lengths to which one might strive to fulfill America’s founding ideals of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. As a former enslaved man, Carney fought and bled for his nation in the hopes of securing freedom for all. For his valorous service to the United States, he became the first Black American to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor. Later in life, Carney humbly said:

“Boys, I only did my duty. The old flag never touched the ground.”

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).