Remembering Bill of Rights Day

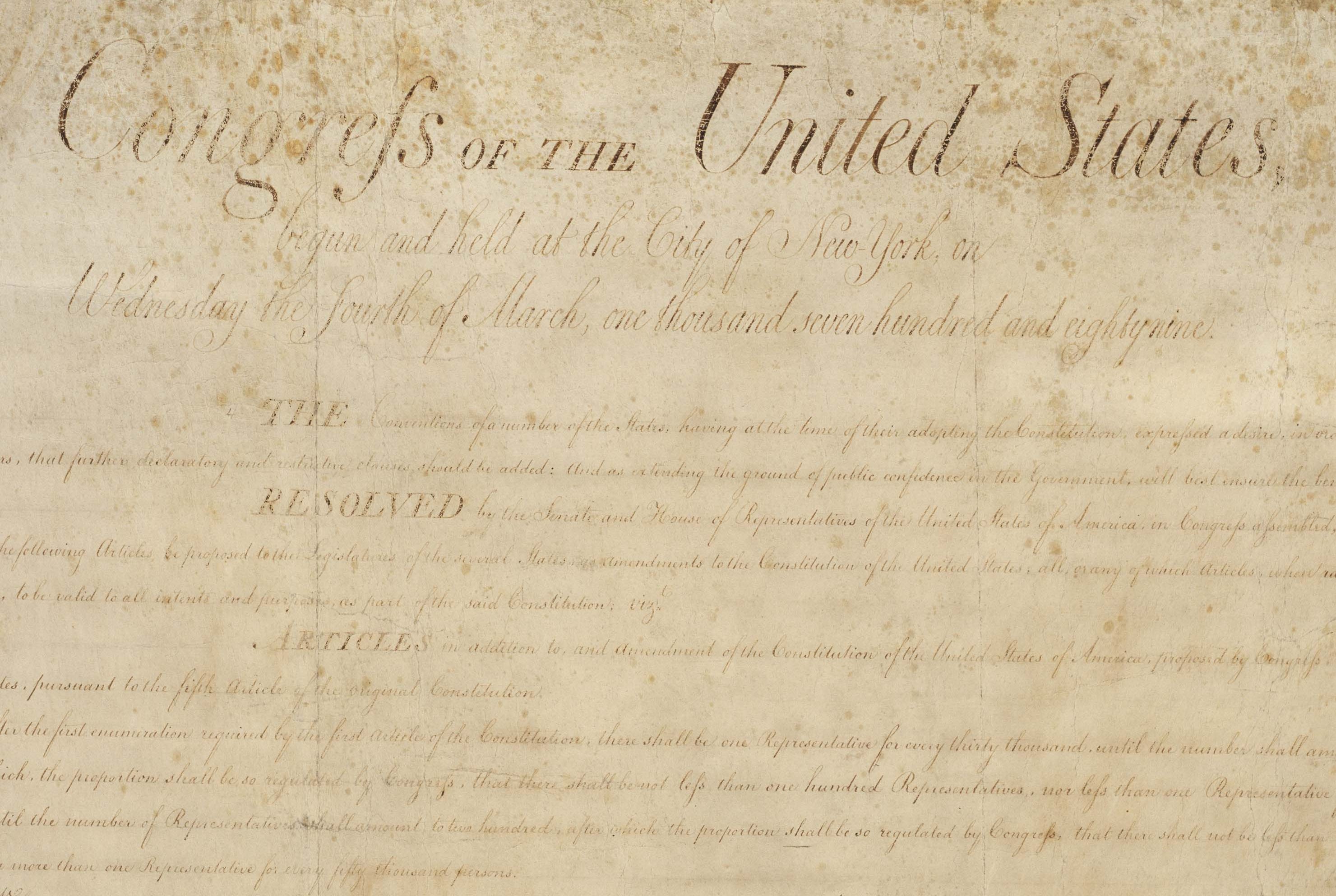

December 15 marks the 228th anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1791. When the U.S. Constitution was initially proposed and ratified, several members of Congress, especially within the antifederalist faction, took issue with its lack of a bill of rights.

Antifederalists argued that a bill of rights would explicitly define the rights of the people, in effect preventing them from being violated. Several state constitutions contained a bill of rights – if the federal government took precedent to state government, it followed that the federal constitution should have one as well. In contrast, federalists such as Alexander Hamilton, did not believe a bill of rights was necessary. Since the government was limited to its delegated powers, it seemed unnecessary to define the rights of the people. In fact, some federalists thought a bill of rights was a dangerous concept – rights omitted may be considered unretained.

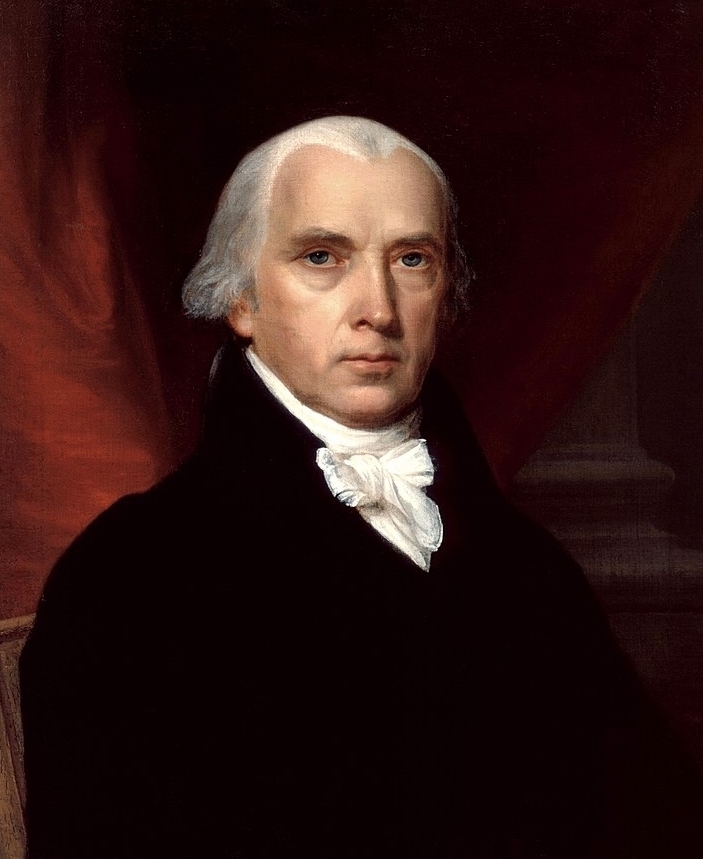

In the end, the antifederalist concerns were heeded as several states ratified the Constitution on the condition that a bill of rights would be added. After the Constitution’s ratification in 1788, James Madison drafted the Bill of Rights, drawing inspiration from the Virginia Declaration of Rights and amendments proposed by the states during ratification. He initially recorded 19 amendments; the House and Senate pared these down to 12 before they were sent to the states for ratification. The first 2 amendments, which pertained to apportionment in the House and pay for Congress, were rejected by the states, leaving the first 10 amendments as we know them today.

Recognition of Bill of Rights Day did not come until its 150th anniversary in 1941. Franklin D. Roosevelt was responsible for proclaiming the first Bill of Rights Day and held a radio address for the occasion. Occurring a mere week after the United States’s entry into World War II, the address praised countries that protected those basic rights enumerated in the Bill of Rights. President Truman sporadically proclaimed a Bill of Rights Day during his presidency, but an annual presidential proclamation did not begin until 1962. Fitting the original international tone of 1941, the proclamation has often been paired with a proclamation for Human Rights Day as well.

In honor of the Bill of Rights and its central role in American law, we present a collection of primary resources, fellows’ articles, and resources on the Bill of Rights. It includes the original arguments for and against a bill of rights, as well as pieces on the founders’ philosophy of rights.

Primary Sources Deliberating a Bill of Rights:

The Push for a Bill of Rights

George Mason, reported from Madison’s Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, September 12, 1787

Col: MASON perceived the difficulty mentioned by Mr. Gorham. The jury cases can not be specified. A general principle laid down on this and some other points would be sufficient. He wished the plan had been prefaced with a Bill of Rights, & would second a Motion if made for the purpose. It would give great quiet to the people; and with the aid of the State declarations, a bill might be prepared in a few hours.

Mr. GERRY concurred in the idea & moved for a Committee to prepare a Bill of Rights.

Col: MASON 2ded. the motion.

Mr. SHERMAN, was for securing the rights of the people where requisite. The State Declarations of Rights are not repealed by this Constitution; and being in force are sufficient. There are many cases where juries are proper which can not be discriminated. The Legislature may be safely trusted.

Col: MASON. The Laws of the U. S. are to be paramount to State Bills of Rights.

On the question for a Come. to prepare a Bill of Rights

N. H. no. Mas. abst. Ct. no. N. J. no. Pa. no. Del no. Md. no. Va. no. N. C. no. S. C. no. Geo. no.

Read more of the debates at Yale’s Avalon Project >>

The Federal Farmer, Letter II, October 9, 1787

…There are certain unalienable and fundamental rights, which in forming the social compact, ought to be explicitly ascertained and fixed—a free and enlightened people, in forming this compact, will not resign all their rights to those who govern, and they will fix limits to their legislators and rulers, which will soon be plainly seen by those who are governed, as well as by those who govern: and the latter will know they cannot be passed unperceived by the former, and without giving a general alarm. These rights should be made the basis of every constitution: and if a people be so situated, or have such different opinions that they cannot agree in ascertaining and fixing them, it is a very strong argument against their attempting to form one entire society, to live under one system of laws only. I confess, I never thought the people of these states differed essentially in these respects; they having derived all these rights from one common source, the British systems; and having in the formation of their state constitutions, discovered that their ideas relative to these rights are very similar. However, it is now said that the states differ so essentially in these respects, and even in the important article of the trial by jury, that when assembled in convention, they can agree to no words by which to establish that trial, or by which to ascertain and establish many other of these rights, as fundamental articles in the social compact. If so, we proceed to consolidate the states on no solid basis whatever…

…There are certain unalienable and fundamental rights, which in forming the social compact, ought to be explicitly ascertained and fixed—a free and enlightened people, in forming this compact, will not resign all their rights to those who govern, and they will fix limits to their legislators and rulers, which will soon be plainly seen by those who are governed, as well as by those who govern: and the latter will know they cannot be passed unperceived by the former, and without giving a general alarm. These rights should be made the basis of every constitution: and if a people be so situated, or have such different opinions that they cannot agree in ascertaining and fixing them, it is a very strong argument against their attempting to form one entire society, to live under one system of laws only. I confess, I never thought the people of these states differed essentially in these respects; they having derived all these rights from one common source, the British systems; and having in the formation of their state constitutions, discovered that their ideas relative to these rights are very similar. However, it is now said that the states differ so essentially in these respects, and even in the important article of the trial by jury, that when assembled in convention, they can agree to no words by which to establish that trial, or by which to ascertain and establish many other of these rights, as fundamental articles in the social compact. If so, we proceed to consolidate the states on no solid basis whatever…

Read the entire letter at TeachingAmericanHistory.org >>

James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, October 24, 1787

…Col. Mason left Philada. in an exceeding ill humour indeed. A number of little circumstances arising in part from the impatience which prevailed towards the close of the business, conspired to whet his acrimony. He returned to Virginia with a fixed disposition to prevent the adoption of the plan if possible. He considers the want of a Bill of Rights as a fatal objection…

…Col. Mason left Philada. in an exceeding ill humour indeed. A number of little circumstances arising in part from the impatience which prevailed towards the close of the business, conspired to whet his acrimony. He returned to Virginia with a fixed disposition to prevent the adoption of the plan if possible. He considers the want of a Bill of Rights as a fatal objection…

Access the rest of the letter at the National Archives >>

Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, December 20, 1787

…I like much the general idea of framing a government which should go on of itself peaceably, without needing continual recurrence to the state legislatures. I like the organization of the government into Legislative, Judiciary & Executive. I like the power given the Legislature to levy taxes…I will now add what I do not like. First the omission of a bill of rights providing clearly & without the aid of sophisms for freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies, restriction against monopolies, the eternal & unremitting force of the habeas corpus laws, and trials by jury in all matters of fact triable by the laws of the land & not by the law of Nations. To say, as mr. Wilson does, that a bill of rights was not necessary because all is reserved in the case of the general government which is not given, while in the particular ones all is given which is not reserved, might do for the Audience to whom it was addressed, but is surely a gratis dictum, opposed by strong inferences from the body of the instrument, as well as from the omission of the clause of our present confederation which had declared that in express terms. It was a hard conclusion to say because there has been no uniformity among the states as to the cases triable by jury, because some have been so incautious as to abandon this mode of trial, therefore the more prudent states shall be reduced to the same level of calamity. It would have been much more just & wise to have concluded the other way that as most of the states had judiciously preserved this palladium, those who had wandered should be brought back to it, and to have established general right instead of general wrong. Let me add that a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, & what no just government should refuse or rest on inference…

…I like much the general idea of framing a government which should go on of itself peaceably, without needing continual recurrence to the state legislatures. I like the organization of the government into Legislative, Judiciary & Executive. I like the power given the Legislature to levy taxes…I will now add what I do not like. First the omission of a bill of rights providing clearly & without the aid of sophisms for freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies, restriction against monopolies, the eternal & unremitting force of the habeas corpus laws, and trials by jury in all matters of fact triable by the laws of the land & not by the law of Nations. To say, as mr. Wilson does, that a bill of rights was not necessary because all is reserved in the case of the general government which is not given, while in the particular ones all is given which is not reserved, might do for the Audience to whom it was addressed, but is surely a gratis dictum, opposed by strong inferences from the body of the instrument, as well as from the omission of the clause of our present confederation which had declared that in express terms. It was a hard conclusion to say because there has been no uniformity among the states as to the cases triable by jury, because some have been so incautious as to abandon this mode of trial, therefore the more prudent states shall be reduced to the same level of calamity. It would have been much more just & wise to have concluded the other way that as most of the states had judiciously preserved this palladium, those who had wandered should be brought back to it, and to have established general right instead of general wrong. Let me add that a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, & what no just government should refuse or rest on inference…

Access the rest of the letter at the National Archives >>

The Case Against a Bill of Rights

Giles Hickory (Noah Webster), “On the Absurdity of a Bill of Rights,” December 1787

One of the principal objections to the new Federal Constitution is, that it contains no Bill of Rights. This objection, I presume to assert, is founded on ideas of government that are totally false. Men seem determined to adhere to old prejudices, and reason wrong, because our ancestors reasoned right. A Bill of Rights against the encroachments of Kings and Barons, or against any power independent of the people, is perfectly intelligible; but a Bill of Rights against the encroachments of an elective Legislature, that is, against our own encroachments on ourselves, is a curiosity in government…

One of the principal objections to the new Federal Constitution is, that it contains no Bill of Rights. This objection, I presume to assert, is founded on ideas of government that are totally false. Men seem determined to adhere to old prejudices, and reason wrong, because our ancestors reasoned right. A Bill of Rights against the encroachments of Kings and Barons, or against any power independent of the people, is perfectly intelligible; but a Bill of Rights against the encroachments of an elective Legislature, that is, against our own encroachments on ourselves, is a curiosity in government…

…I undertake to prove that a standing Bill of Rights is absurd, because no constitutions, in

a free government, can be unalterable. The present generation have indeed a right to declare what they deem a privilege; but they have no right to say what the next generation shall deem a privilege…

Read the rest of Webster’s argument at the Library of America >>

Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 84 (July 16-August 9, 1788):

…I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and to the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed Constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and, on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why, for instance, should it be said that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretense for claiming that power. They might urge with a semblance of reason, that the Constitution ought not to be charged with the absurdity of providing against the abuse of an authority which was not given, and that the provision against restraining the liberty of the press afforded a clear implication, that a power to prescribe proper regulations concerning it was intended to be vested in the national government. This may serve as a specimen of the numerous handles which would be given to the doctrine of constructive powers, by the indulgence of an injudicious zeal for bills of rights…

…I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and to the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed Constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and, on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why, for instance, should it be said that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretense for claiming that power. They might urge with a semblance of reason, that the Constitution ought not to be charged with the absurdity of providing against the abuse of an authority which was not given, and that the provision against restraining the liberty of the press afforded a clear implication, that a power to prescribe proper regulations concerning it was intended to be vested in the national government. This may serve as a specimen of the numerous handles which would be given to the doctrine of constructive powers, by the indulgence of an injudicious zeal for bills of rights…

Read more of Federalist 84 at Yale’s Avalon Project >>

Click here for an excellent listing of Federalist and Antifederalist arguments both for and against a bill of rights at UW-Madison’s Center for the Study of the American Constitution >>

JMC’s First Amendment Library:

The Jack Miller Center’s website has a treasure trove of resources on the freedom of speech and religious liberty. The JMC First Amendment Library includes sections on the history, law, and theory behind these First Amendment rights. Learn about the most fundamental origins of freedom of speech and religious liberty, the American view of them, and controversies that have arisen in the past 232 years.

The Jack Miller Center’s website has a treasure trove of resources on the freedom of speech and religious liberty. The JMC First Amendment Library includes sections on the history, law, and theory behind these First Amendment rights. Learn about the most fundamental origins of freedom of speech and religious liberty, the American view of them, and controversies that have arisen in the past 232 years.

Explore the entire First Amendment Library >>

Passage of the Bill of Rights

Passage of the Bill of Rights

Only a month after the Constitution was printed and distributed, the first ratifying convention took place in Pennsylvania. The ratification process went relatively smoothly for a couple months after that, with five state conventions approving ratification with little difficulty. In January of 1788, however, the ratifying convention in Massachusetts devolved into a bitter and even violent deadlock, largely over the question of a bill of rights. Only by promising to introduce a Bill of Rights as amendments were the Federalist supporters of the Constitution able to break the deadlock and secure ratification in Massachusetts. Without this strategy, which was subsequently adopted in other states with Federalist minorities, the Constitution could not have been ratified. Despite the reservations of many of the Federalists, who had a commanding majority in the first Congress, James Madison recognized the necessity of keeping their promise and adding a Bill of Rights quickly in order to secure the legitimacy of the new government. He submitted a proposal for seventeen amendments based on the Virginia Declaration of rights early in 1789. This proposal went through four stages of rigorous debate and revision in the House and the Senate before being approved by Congress in September of 1789. Of the twelve articles in the approved amendments, ten were ratified as by the states over the course of the next two years, becoming what is now known as our Bill of Rights. The first of these ten included the provision that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

Read more about the Bill of Rights in our First Amendment Library >>

A Few Supreme Court Cases Pertinent to the Bill of Rights

Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940)

Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940)

In Cantwell v. Connecticut, the Court applied the Free Exercise Clause to state and local government for the first time. Prior to the Fourteenth Amendment, constitutional rights, such as those enumerated in the Bill of Rights, applied only to the federal government. In the Cantwell decision, the Free Exercise clause from the First Amendment was “incorporated” into the Court’s understanding of the protections guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment against both federal and state authority.

Read more in the First Amendment library >>

Everson v. Board of Education (1947)

Everson v. Board of Education (1947)

Griswold v. Connecticut (1965)

Griswold v. Connecticut (1965)

Commentary and articles from JMC fellows:

The Bill of Rights

Jeremy Bailey, “Was James Madison ever for the bill of rights?“ (Perspectives on Political Science 41.2, 2012)

Michael Douma, “How the First Ten Amendments became the Bill of Rights.” (Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy 15.2, 2017)

Michael Douma, “How the First Ten Amendments became the Bill of Rights.” (Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy 15.2, 2017)

Justin Dyer (co-author), American Constitutional Law, Vol. 2: Liberty, Community, and the Bill of Rights. (West Academic Publishing, 2018)

Michael Faber, Our Federalist Constitution: The Founders’ Expectations and Contemporary Government. (LFB Scholarly Publishing, 2010)

Arthur Milikh, “Franklin and the Free Press.” (National Affairs, March 1, 2017)

Arthur Milikh, “Rethinking the Bill of Rights.” (National Review, December 15, 2016)

Thomas Pangle, “The Philosophical Roots of the Bill of Rights: The Federalists’ and Anti-Federalists’ Conceptions of Rights.” (The Political Science Teacher 3.2, Spring 1990)

Thomas Pangle, “The Philosophical Roots of the Bill of Rights: The Federalists’ and Anti-Federalists’ Conceptions of Rights.” (The Political Science Teacher 3.2, Spring 1990)

Thomas West, “The Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.” (The Declaration of Independence: Origins and Impact, CQ Press, 2002)

Keith Whittington (co-author), American Constitutionalism: Powers, Rights, and Liberties. (Oxford University Press, 2014)

Keith Whittington (co-author), American Constitutionalism, Volume 2: Rights and Liberties. (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Specific Amendments in the Bill of Rights

Sotirios Barber, “National League of Cities v. Usery: New Meaning for the Tenth Amendment?“ (The Supreme Court Review, 1976)

Sotirios Barber, “National League of Cities v. Usery: New Meaning for the Tenth Amendment?“ (The Supreme Court Review, 1976)

Sotirios Barber, “The Ninth Amendment: Inkblot or Another Hard Nut to Crack?“ (Chicago-Kent Law Review 64.1, April 1988)

Kevin Burns, “The Fourth Amendment: Searches, Seizures, and Privacy.” (Constitutional Government: The American Experience, Kendall Hunt Publishing Co., 2016)

Luke Sheahan, “The First Amendment Dyad and Christian Legal Society v. Martinez: Getting Past ‘State’ and ‘Individual’ to Help the Court ‘See’ Associations.” (Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy, XXVII.2, May 30, 2018)

Natural Rights: Political Philosophy and Its Influence on the Founders

Mark Blitz, “The Character of Executive and Legislative Power in a Regime Based on Natural Rights.” (The Revival of Constitutionalism, University of Nebraska Press, 1988)

Mark Blitz, “The Character of Executive and Legislative Power in a Regime Based on Natural Rights.” (The Revival of Constitutionalism, University of Nebraska Press, 1988)

Mark Blitz, “Radical Historicism and the Meaning of Natural Right.” (Modern Age 28.2, Spring/Summer 1984)

Paul Carrese, “Montesquieu’s Complex Natural Right and Moderate Liberalism: The Roots of American Moderation.” (Polity 36.2, 2004)

Justin Dyer, “Natural Rights.” (American Governance, Macmillan, 2016)

Justin Dyer (co-author), “Thomas Jefferson, Nature’s God, and the Theological Foundations of Natural-Rights Republicanism.” (Politics & Religion 10.3, 2007)

Justin Dyer, “Unenumerated Rights.” (American Governance, Macmillan, 2016)

Robert Faulkner, “Natural Law: Richard Hooker (1554-1600).” (Natural Law, Natural Rights, and American Constitutionalism, 2014)

Robert Faulkner, “Natural Law: Richard Hooker (1554-1600).” (Natural Law, Natural Rights, and American Constitutionalism, 2014)

Lauren Hall, “Rights and the Heart: Emotions and Rights Claims in the Political Theory of Edmund Burke.” (Review of Politics 73.4, 2011)

Charles Kesler, “Natural Right in the American Revolution.” (Three Beginnings: Revolution, Rights and the Liberal State, Peter Lang Publishing, 1994)

Charles Kesler, “Natural Law and a Limited Constitution.” (University of Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Review 4.3, 1995)

David Lieberman, “Adam Smith on Justice, Rights, Law.” (Cambridge Companion to Adam Smith, Cambridge University Press, 2006)

Thomas Merrill, “The Later Jefferson and the Problem of Natural Rights.” (Perspectives on Political Science 44.2, April 2015)

Svetozar Minkov (editor), Toward “Natural Right and History”: Lectures and Essays by Leo Strauss, 1937-1946. (University of Chicago Press, 2018)

Svetozar Minkov (editor), Toward “Natural Right and History”: Lectures and Essays by Leo Strauss, 1937-1946. (University of Chicago Press, 2018)

James Russell Muirhead, “The Prudential Path of Natural Rights.” (Law and Liberty Forum, October 15, 2015)

Vincent Philip Muñoz, “If Religious Liberty Does Not Mean Exemptions, What Might It Mean? The Founders’ Constitutionalism of the Inalienable Rights of Religious Liberty.” (Notre Dame Law Review 91.4, 2016)

Vincent Philip Muñoz, “Natural Rights, God, and Marriage in the American Founding.” (Public Discourse, May 23, 2018)

Laura Beth Nielsen (editor), Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives on Rights. (Ashgate, 2007)

Thomas Pangle, “The Liberal Critique of Rights in Montesquieu and Hume.” (La Revue Tocqueville/The Tocqueville Review 13.2, 1992)

Thomas Pangle, “The Philosophic Conception of Rights Informing the Constitution.” (The Public Interest Law Review 1, 1991)

Thomas Pangle (co-author), “The Philosophic Foundation of Human Rights.” (Human Rights in Our Time, Westview, 1984)

Thomas Pangle (co-author), “The Philosophic Foundation of Human Rights.” (Human Rights in Our Time, Westview, 1984)

Thomas Pangle, “Republicanism and Rights.” (The Framers and Fundamental Rights, AEI, 1991)

Stephen Presser, “Natural Rights.” (The Dictionary of American History, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2003)

Michelle Schwarze (co-author), “Reconciling Natural Rights and the Moral Sense: Francis Hutcheson and American Political Thought.” (Promise and Peril: Republics and Republicanism in the History of Political Philosophy, Mercer University Press, 2017)

S. Adam Seagrave, The Foundations of Natural Morality: On the Compatibility of Natural Rights and the Natural Law. (University of Chicago Press, 2014)

S. Adam Seagrave, “How Old Are Modern Rights? On the Lockean Roots of Contemporary Human Rights Discourse.” (Journal of the History of Ideas 72.2, April 2011)

S. Adam Seagrave, “Locke on the Laws of Nature and Natural Rights.” (A Companion to Locke, Wiley-Blackwell, 2015)

S. Adam Seagrave, “Locke on the Laws of Nature and Natural Rights.” (A Companion to Locke, Wiley-Blackwell, 2015)

S. Adam Seagrave, “Why Is America Important? Michael Zuckert’s Lockean Natural Rights Theory.” (American Political Thought 8.2, May 30, 2019)

James Stoner (co-author), “Natural Law and Property Rights.” (Natural Law, Economics, and the Common Good: Perspectives from Natural Law, Imprint Academic, 2012)

Thomas West, “The Ground of Locke’s Law of Nature.” (Social Philosophy and Policy 29.2, Summer 2012)

Thomas West, The Political Theory of the American Founding: Natural Rights, Public Policy, and the Moral Conditions of Freedom. (Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Jean Yarbrough, “Federalism and Rights at the Founding.” (Federalism and Rights, Rowman & Littlefield, 1996)

Jean Yarbrough, “Jefferson and Property Rights.” (Liberty, Property and the Foundations of the American Constitution, State University of New York Press, 1989)

Michael Zuckert, “‘Bringing Philosophy Down from the Heavens’: Natural Right in the Roman Law.” (Review of Politics 51.1, Winter 1989)

Michael Zuckert, “‘Bringing Philosophy Down from the Heavens’: Natural Right in the Roman Law.” (Review of Politics 51.1, Winter 1989)

Michael Zuckert, “Do Natural Rights Derive from Natural Law?” (Harvard Journal of Policy and Legislation, 1998)

Michael Zuckert, “English Radical Whigs and Natural Law.” (Witherspoon Institute’s Natural Law, Natural Rights and American Constitutionalism, Online Resource Center, 2009)

Michael Zuckert, “Natural Law, Natural Rights and Classical Liberalism: Montesquieu’s Critique of Hobbes.” (Natural Law and Modern Moral Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, 2000)

Michael Zuckert, “Natural Rights and Imperial Constitutionalism: the American Revolution and the Development of the American Amalgam.” (Social Philosophy and Policy 22.1, Winter 2005)

Michael Zuckert, Natural Rights and the New Republicanism. (Princeton University Press, 1994)

Michael Zuckert, “Natural Rights and the Post Civil War Amendments.” (Witherspoon Institute’s Natural Law, Natural Rights and American Constitutionalism, Online Resource Center, 2009)

Michael Zuckert, “Natural Rights and the Post Civil War Amendments.” (Witherspoon Institute’s Natural Law, Natural Rights and American Constitutionalism, Online Resource Center, 2009)

Michael Zuckert, The Natural Rights Republic. (University of Notre Dame Press, 1996)

Michael Zuckert, “Reconsidering Lockean Rights Theory.” (Interpretation 32.3, Fall 2005)

Michael Zuckert, “Thomas Jefferson and Natural Morality: Classical Moral Theory, Moral Sense, and Rights.” (Thomas Jefferson, the Classical World, and Early America, University of Virginia Press, 2011)

Michael Zuckert, “Thomas Jefferson on Nature and Natural Rights.” (The Framers and Fundamental Rights, AEI Press, 1992)

Thomas Jefferson and the Politics of Nature (essays in response to Michael Zuckert’s Natural Rights Republic). (University of Notre Dame Press, 2000)

Rights in American Political Development

Paul Carrese, “Montesquieu, the Founders, and Woodrow Wilson: The Evolution of Rights and the Eclipse of Constitutionalism.” (The Progressive Revolution in Politics and Political Science, Rowman & Littlefield, 2005)

Paul Carrese, “Montesquieu, the Founders, and Woodrow Wilson: The Evolution of Rights and the Eclipse of Constitutionalism.” (The Progressive Revolution in Politics and Political Science, Rowman & Littlefield, 2005)

James Ceaser, “Progressivism and the Doctrine of Natural Rights.” (Progressive Challenges to the American Constitution, Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Justin Dyer, “Lincolnian Natural Right, Dred Scott, and the Jurisprudence of John McLean.” (Polity 41.1, 2009)

Gianna Englert, “‘The Idea of Rights’: Tocqueville on the Social Question.” (The Review of Politics 79.4, 2017)

Michael Faber, “Democratic Anti-Federalism: Rights, Democracy, and the Minority in the Pennsylvania Ratifying Convention.” (Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 138.2, 2014)

Charles Kesler, “The Nature of Rights in American Politics: A Comparison of Three Revolutions.” (Heritage Foundation’s First Principles Series, September 30, 2008)

Michael Zuckert, “Fundamental Rights, the Supreme Court and American Constitutionalism: The Lessons of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.” (The Supreme Court and American Constitutionalism, Rowman & Littlefield, 1997)

Understanding Rights Today

Madeline Ahmed Cronin (co-author), “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman within the Women’s Human Rights Tradition, 1739-2015.” (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Yale University Press, 2014)

Madeline Ahmed Cronin (co-author), “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman within the Women’s Human Rights Tradition, 1739-2015.” (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Yale University Press, 2014)

James Ceaser (co-author), “Liberty and Rights in American and British Conservatism.” (Reflections on Conservative Politics in the United Kingdom and the United States: Still Soul Mates?, Lexington Books, 2012)

Nancy Hirschmann, “Difference as an Occasion for Rights: A Feminist Rethinking of Rights, Liberalism, and Difference.” (Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 2.1, Summer 1999)

Nancy Hirschmann, “Disability Rights, Social Rights, and Freedom.” (Journal of International Political Theory 12.1, 2016)

Andrew Lewis, “Divided over Rights: Competing Evangelical Visions for Twenty-First Century America.” (The Evangelical Crackup: The Future of the Evangelical-Republican Coalition, Temple University Press, 2018)

Andrew Lewis (co-author), “Freedom of Religion and Freedom of Speech: The Effects of Alternative Rights Frames on Mass Support for Public Exemptions.” (Journal of Church and State 60.1, Winter 2018)

Andrew Lewis (co-author), “Freedom of Religion and Freedom of Speech: The Effects of Alternative Rights Frames on Mass Support for Public Exemptions.” (Journal of Church and State 60.1, Winter 2018)

Andrew Lewis (co-author), “Rights Talk: The Opinion Dynamics of Rights Framing.” (Social Science Quarterly 95.3, 2014)

Emma Mackinnon, “Declaration as Disavowal: The Politics of Race and Empire in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” (Political Theory, June 20, 2018)

Laura Beth Nielsen (co-author), “Dignity and Discrimination: Employment Civil Rights in the Workplace and in Courts.” (Chicago-Kent Law Review 92.3, 2017)

Laura Beth Nielsen, “Good Moms with Guns: Individual and Relational Rights in the Home, Family, and Society.” (Guns in Law, University of Massachusetts Press, 2019)

Laura Beth Nielsen, “The Power of Place in the Construction of Rights.” (New Civil Rights Research: A Constitutive Approach, Dartmouth/Ashgate Press, 2006)

Laura Beth Nielsen, “Understanding Rights.” (Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives on Rights, Ashgate, 2006)

Laura Beth Nielsen, “Understanding Rights.” (Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives on Rights, Ashgate, 2006)

Laura Beth Nielsen, “The Work of Rights and the Work That Rights Do.” (Blackwell Companion to Law and Society, Blackwell, 2004)

Stephen Presser, “Commercial Speech and the First Amendment: Cigarette Companies and the Playboy Channel Have Rights Too–Or Do They?” (Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture, October 2000)

Stephen Presser, “The Rights of Aliens: ‘ We The People’ versus Human Rights.” (Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture, May 2003)

Robert Saldin, “Wartime: Foreign Conflict and Domestic Rights.” (World Affairs, July/August 2012)

Rogers Smith, “Alien Rights, Citizen Rights, and the Politics of Restriction.” (Debating Immigration, Cambridge University Press, 2007)

Rogers Smith, “Alien Rights, Citizen Rights, and the Politics of Restriction.” (Debating Immigration, Cambridge University Press, 2007)

Rogers Smith, “National Obligations and Non-Citizens: Special Rights, Human Rights, and Immigration.” (Politics & Society 42.3, 2014)

Rogers Smith, “The Politics of Rights, Then and Now.” (The Nature of Rights at the American Founding and Beyond, University of Virginia Press, 2007)

Rogers Smith, “Understanding the Symbiosis of American Rights and American Racism.” (The American Liberal Tradition Reconsidered: The Contested Legacy of Louis Hartz, University of Kansas Press, 2010)

Emily Zackin, Looking for Rights in All the Wrong Places: Why State Constitutions Contain America’s Positive Rights. (Princeton University Press, 2013)

*If you are a JMC fellow who’s published on the Bill of Rights or its history, development, or controversies, and would like your work included here, send it to us at academics@gojmc.org.

More resources for Bill of Rights Day:

Bill of Rights Day at the National Constitution Center

Bill of Rights Day at the National Constitution Center

The National Constitution Center offers educational videos on the Bill of Rights, as well as an interactive Constitution, which features essays on each of the Bill of Rights amendments, written by top experts on the Constitution from across the political spectrum. Visitors to the Center can participate in special constitutional trivia games and tours on Bill of Rights Day.

Visit the National Constitution Center website >>

A Library of Congress Guide to the Bill of Rights

A Library of Congress Guide to the Bill of Rights

The Library of Congress website features both an online exhibit and web guide for the Bill of Rights. The online exhibit, “Creating the United States,” tracks the origins of the Bill of Rights using primary documents, including a speech that describes the it as “little better than whipsyllabub, frothy and full of wind.” The web guide also offers an extensive collection of resources on the Bill of Rights and the thought process behind it.

Visit “Creating the United States” here and the Bill of Rights web guide here >>

The National Archives

The National Archives

The National Archives, home of the Bill of Rights, has videos, teaching and learning resources, and articles on its website. This year, the National Archives held a program on December 12 in which a panel of scholars and authors explored the unique history of the first 10 amendments and the ways in which they have influenced national constitutions around the world from 1791 to today.

Visit the National Archives >>

The Anti-Federalist Papers

The Anti-Federalist Papers

FederalistPapers.org has gathered together some of the most-widely read arguments made against the ratification of the Constitution, including the concern that it lacked a bill of rights. Collectively, these writings have come to be known as the Anti-Federalist Papers and contain warnings that the proposed Constitution did not adequately provide against the danger of tyranny.

Read the Anti-Federalist Papers at the FederalistPapers.org >>

*If you are a JMC fellow who’s published on the Bill of Rights or its history, development, or controversies, and would like your work included here, send it to us at academics@gojmc.org.

![]()

![]() Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.