John Agresto: Civic Education and Patriotism

On October 3, 2019 JMC board member John Agresto delivered the keynote address at the Jack Miller Center’s 2019 Summit on Higher Education. Focusing on the theme of the summit, “Should America’s Colleges Teach Patriotism?” Dr. Agresto spoke on true patriotism and its relationship to civic knowledge.

Teaching Patriotism

Below, a transcript of Dr. Agresto’s keynote address, delivered October 3, 2019 at the Jack Miller Center Summit for Higher Education in Chicago, IL:

Thank you, Jack [Miller], Mike [Andrews]…

My father was born in 1920, and, when the war broke out, he went and joined the navy. He fought all of World War II in the Pacific on a light cruiser called the Wichita. When the war was over, he came back to New York and worked unloading trucks at the Fulton Street Vegetable Market. Then he tried owning a bar in Brooklyn. When that failed, he became a day laborer in construction. A hod-carrier, he poured cement at different construction sites for the rest of his life.

My father was born in 1920, and, when the war broke out, he went and joined the navy. He fought all of World War II in the Pacific on a light cruiser called the Wichita. When the war was over, he came back to New York and worked unloading trucks at the Fulton Street Vegetable Market. Then he tried owning a bar in Brooklyn. When that failed, he became a day laborer in construction. A hod-carrier, he poured cement at different construction sites for the rest of his life.

He was an ordinary person, not fancy at all. You might say he was far more prosaic than poetic. But there was one poem he liked and would say to us kids now and then. He must have learned it in seventh or eighth grade since he never made it to high school. It was an old poem by Sir Walter Scott. It goes like this:

Breathes there the man, with soul so dead,

Who never to himself hath said,

This is my own, my native land!

Whose heart hath ne’er within him burn’d,

As home his footsteps he hath turn’d,

From wandering on a foreign strand?

If such there breathe, go, mark him well;

For him no Minstrel raptures swell;

…

The wretch, concentred all in self,

[Shall quickly] forfeit fair renown,

And, doubly dying, shall go down

To the vile dust, from whence he sprung,

Unwept, unhonour’d, and unsung.

Teach patriotism? Seems unnecessary–it’s seemingly natural. Only those with dead souls don’t love their country.

We sometimes hear countries called “our fatherland,” or maybe “our motherland.” We often love it as we love our own, as part of ourselves, because, for some inbred, natural reason, all humans love their own. We know that.

For example, no matter how wonderful, how lovely, other parents’ children are, and no matter how disappointing your own kids might be, it still takes an immense effort of the will to love other people’s kids more than your own.

The same seems to be true with love of country. If love of one’s own is as natural to being human as love of ourselves, why would we ever even think it necessary to teach people to love their native land?

Why? Because, natural or not, I think we all understand that patriotism can be undermined and twisted. And, in America today, it is being twisted.

I spent much of my adult life as a president of or professor in some very fine colleges and universities. And I am not one who is comfortable painting schools and colleges with so broad a brush as to say that they are, each and all, corrupting our kids and turning children against their country. But we all know that some, perhaps many are. So, the question we have to get to is: What can we do about it?

I spent much of my adult life as a president of or professor in some very fine colleges and universities. And I am not one who is comfortable painting schools and colleges with so broad a brush as to say that they are, each and all, corrupting our kids and turning children against their country. But we all know that some, perhaps many are. So, the question we have to get to is: What can we do about it?

But to know how to remedy this problem, we first have to ask what’s causing so many teachers and their students to actively dislike their country.

Now, from what I can see, this undermining is done in a few ways – for example, these days we all have to be “critical thinkers.” This rarely means careful thinking, or systematic thinking, or analytic thinking, or, heaven forbid, just plain Thinking. To be critical often means exactly that – being critical: we have to criticize everyone and everything that went before. Now, our students are hardly critical of themselves, since so many of them are led to believe, perhaps even encouraged to believe, that their generation knows more and better about all the important things. All too often, critical thinking has taken the place once occupied by plain, old Thinking, or what we often just used to call Understanding.

Second, in some schools and colleges our students often read only those things that support their positions or their identity. Things contrary to, or ideas and books that might work to undermine their ideas and notions, trigger unhappy feelings. And neither students nor their professors and teachers want to be made uncomfortable. So, do I think these institutions of great learning should teach patriotism? Can you imagine what a mess they would make of it? Why would you trust them?

Third, you know the sad content of much of contemporary history and civic education: the American Founders were racist, sexist, homophobic rich white guys. From that, it follows that the country they established must be the same – racist, sexist, unequal, unjust, and pretty much evil.

But maybe the worst part of education today is not the misuse of the idea of “critical thinking,” perhaps not even the thought that all knowledge is progressive and we, living today, know better than those who lived before. Perhaps the worst is not even the propaganda that our Fathers were evil, racist, old and white. Perhaps the worst thing is summed up in the word I used a few seconds ago – “identity.” We are taught in schools, in popular culture, in movies, in you name it, that the thing that defines us, the thing that we should be most attached to, devoted to, and love is our “identity.” This thing that is most important to us always seems to be something narrow, not something grand. Perhaps it’s our race, our sexual orientation or preference, our particular religion or sect, our color or ethnicity – everything but our identification, our identity, as simply “Americans.”

But maybe the worst part of education today is not the misuse of the idea of “critical thinking,” perhaps not even the thought that all knowledge is progressive and we, living today, know better than those who lived before. Perhaps the worst is not even the propaganda that our Fathers were evil, racist, old and white. Perhaps the worst thing is summed up in the word I used a few seconds ago – “identity.” We are taught in schools, in popular culture, in movies, in you name it, that the thing that defines us, the thing that we should be most attached to, devoted to, and love is our “identity.” This thing that is most important to us always seems to be something narrow, not something grand. Perhaps it’s our race, our sexual orientation or preference, our particular religion or sect, our color or ethnicity – everything but our identification, our identity, as simply “Americans.”

Now, the few paragraphs I just spoke are true, but not completely true. I said I didn’t want to paint with too broad a brush for one simple reason: there are a number, a very good number, of schools and colleges that aren’t as I just said. Many of them are small and private, many are religious, and some – I have to tell you – are major private and public universities. Why some places have been able to resist the four trends I just mentioned, I hope we can get to in a bit.

But first let’s ask a question, a serious question – if being patriotic is natural for most human beings, if the poem is right that those who do not love their country have seriously dead souls, why is it that we have a problem? Have we always had this problem? Do all countries have this problem?

Let me take you back to the time of our American Founding – to the time when we declared our independence and wrote our constitution. We must have been one country then, no? A place full of patriotic men and women, people willing to sacrifice (as the Declaration of Independence says) their fortunes, their honor, and even their lives? Well, maybe not. If we look back to those days, it looks like we weren’t all that unified in our devotion to this new country of ours. Probably a third of the colonists were still loyal to Great Britain, a third were patriots and fought for us to be free, and roughly another third, from what I’ve heard, just tried to sit it out.

Even the Declaration of Independence itself hints at this lack of devotion to our new country – it declares that we were “United Colonies,” but it also notes that we were thirteen “free and independent states.” So, given that bifurcation, which should we say was “our own, our native land?” The united states, or the individual state in which we might reside? This problem was at the heart of so much of the turmoil in our early history. Think of poor Robert E. Lee. To which community did he owe his allegiance, his devotion? To the people of Virginia or to the people of the United States?

You probably know that in the years before the Civil War we already understood that we had this problem – the opponents of the Constitution, the Anti-Federalists as they came to be called, said that there had never been a republic or a democracy in all of human history that was big and diverse. Only little countries could be real democracies – countries more like cities than whole nations. And, if they were larger, they had to be unified and homogeneous. They had to have an “identity” that every citizen could identify with – perhaps all Catholics, or all Jews, or all Spaniards or Japanese. And even there, fractures and factions could easily split the country into civil war.

You probably know that in the years before the Civil War we already understood that we had this problem – the opponents of the Constitution, the Anti-Federalists as they came to be called, said that there had never been a republic or a democracy in all of human history that was big and diverse. Only little countries could be real democracies – countries more like cities than whole nations. And, if they were larger, they had to be unified and homogeneous. They had to have an “identity” that every citizen could identify with – perhaps all Catholics, or all Jews, or all Spaniards or Japanese. And even there, fractures and factions could easily split the country into civil war.

But our Founders knew that we couldn’t be unified in terms of, let’s say, religion or ethnicity. In the original 13 states we were Anglicans, Lutherans, Congregationalists, Baptists, Catholics; we were English and Scottish, German and Scandinavian and Dutch. We were split among farmers and merchants and those who worked the seas and the rivers. We were, from the beginning, as diverse and pluralistic – you might even say multi-cultural – as the political mind could imagine. We couldn’t be unified by blood; we couldn’t – as other places might – give our devotion to one sect, or one extended family, or one tribe, or one common way of life.

If patriotism is built on love of one’s own, what exactly is our own, what do we, as diverse Americans, have in common, hold in common, that could claim our loyalty and to which we might be devoted? In other words, what is our singular American identity?

From the Declaration of Independence to the Federalist Papers to the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, what our Fathers hoped we would grow in devotion to – what we would make our own – was something hardly tangible. It was the idea of the equality of all men in their possession of equal rights and equal liberty. It would be this devotion to an idea that would lead us to attach ourselves to this country. It would be a country that, with great difficulty and with many missteps and failures, would protect our rights and provide us with equal justice under law. It would be that country and those principles which would hold us together and even help us respect, perhaps even love, our neighbors, our fellow Americans, with whom we share no common blood, no creed, no family relation. It was devotion to the country built on the idea of equality, rights, and freedom that led my father – an Italian-American who quoted Scottish poets – to fight in a war alongside Jews and Irishmen, Hispanics from New Mexico (who died by the hundreds fighting for America in the Bataan Death March), plus everyone else, from West Virginia mountain men to Navajo code talkers. They understood something about the promise of America which, even if it wasn’t perfect or perfectly applied, commanded their love and devotion and transcended their different backgrounds and, dare I say, their different “identities.”

I want to read something that has always moved me. It’s a talk Abraham Lincoln gave here in Chicago just after the Fourth of July in 1858. It goes like this:

We are now a mighty nation, we are thirty — or about thirty — million people, and we own and inhabit about one-fifteenth part of the dry land of the whole earth. We run our memory back over the pages of history for about eighty-two years. There we discover that we were, then, a very small people, vastly inferior to what we are now, with a considerably smaller extent of territory and, indeed, less of everything we deem desirable among men.

We are now a mighty nation, we are thirty — or about thirty — million people, and we own and inhabit about one-fifteenth part of the dry land of the whole earth. We run our memory back over the pages of history for about eighty-two years. There we discover that we were, then, a very small people, vastly inferior to what we are now, with a considerably smaller extent of territory and, indeed, less of everything we deem desirable among men.

We look upon these changes as exceedingly advantageous to us, and we fix upon something that happened away back, as in some way or other being connected with this rise of our prosperity. We find a race of men living in that day whom we claim as our fathers and grandfathers; they were iron men, men who fought and died for the principle they were contending for. And we understood, because of what they did, that the degree of prosperity that we now enjoy has come to us. We hold these annual Independence Day celebrations to remind ourselves of all the good that was done in this process of time, of how it was done and who did it, and how we are historically connected with it. We go from these meetings [feeling] more attached to one other and more firmly bound to the country we inhabit. In every way, we are better for these celebrations.

But after we have done all this we have not yet reached the whole. There is something else connected with it. We have besides these men—descended by blood from our ancestors—among us perhaps half our people who are not descendants at all of these men. They are men who have come from Europe—German, Irish, French and Scandinavian—men that have come from Europe themselves, or whose ancestors have come hither and settled here, finding themselves our equals in all things. If they look back through this history to trace their connection with those days by blood, they find they have none, they cannot carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us. But when they look through that old Declaration of Independence they find that those old men say that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then they feel that that moral sentiment, taught in that day, evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, and so they are.

That is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.

So how should we go about teaching patriotism in our schools? I believe that the way to counter those who feel called to demean the achievements of this country and undermine the natural affection we all should feel for it, is not by moralizing demands or preachy lectures, but by the clarity and strength of our understanding. I firmly believe that understanding buttresses affection — that even if patriotism is natural, it is surely refined and reinforced by understanding; that trying to encourage patriotism not grounded in knowledge will be shallow, or perhaps worse.

But if we wish to inculcate this kind of intelligent patriotism — if we wish students and our fellow citizens to respect this country and what it stands for — where do we turn?

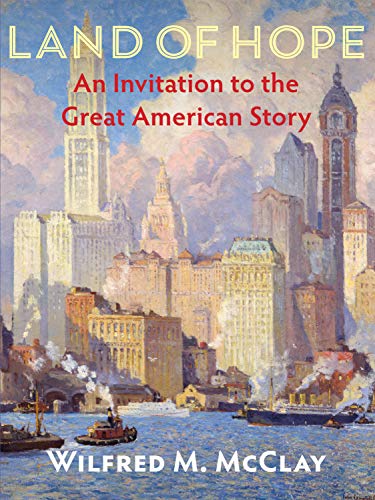

We could start, of course, with educating parents. Most of them know in their hearts that the founding principles of this nation are just, rare, and worthy of transmission from their generation to the next. Many parents I know are desperate to find articles and books to help them understand what they love. Here I have to commend the Miller Center. Professors connected to the JMC work hard at publishing good books, articles, and op-eds accessible to regular citizens, writings that help everyone understand better the meaning of America. In fact, one professor on the Miller board, Bill McClay, just published this year perhaps the best (and best-selling) book on American History in decades – it’s called Land of Hope, An Invitation to the Great American Story.

We could start, of course, with educating parents. Most of them know in their hearts that the founding principles of this nation are just, rare, and worthy of transmission from their generation to the next. Many parents I know are desperate to find articles and books to help them understand what they love. Here I have to commend the Miller Center. Professors connected to the JMC work hard at publishing good books, articles, and op-eds accessible to regular citizens, writings that help everyone understand better the meaning of America. In fact, one professor on the Miller board, Bill McClay, just published this year perhaps the best (and best-selling) book on American History in decades – it’s called Land of Hope, An Invitation to the Great American Story.

There are others involved in this project – literally hundreds of teachers and university professors who work in their classes to transmit our Founding and Constitutional principles. It has been the hope of all of us that rediscovering the meaning of the Founders’ principles and the reasons behind them might help set us back right. This means finding those extraordinary professors and teachers who are not afraid to be old fashioned and teach their students about the American Founding. Not afraid to help students understand what the Founders were trying to accomplish and why. Not deterred from understanding what they did, respecting what they did, and then transmitting all that they did to their students.

Tearing down is easy. The tendency to promote our own more contemporary notions while rejecting or even belittling ideas that went before helps us view ourselves as truly “critical” thinkers, and makes us feel better about ourselves. But maybe, just maybe, if we can help teachers take the Founding seriously and try to understand what today seems so easy to dismiss, we all might learn something — something truly valuable not only for ourselves, but also for our students and for our country. Want to teach kids to love their country? Have them understand all that America has accomplished in this chaotic and tearful world, and the reasons, the ideas, the principles behind those amazing accomplishments. In other words, teach them the fullness of what the American Founding achieved and the reasons and ideas that allowed those accomplishments to unfold.

Thank you.

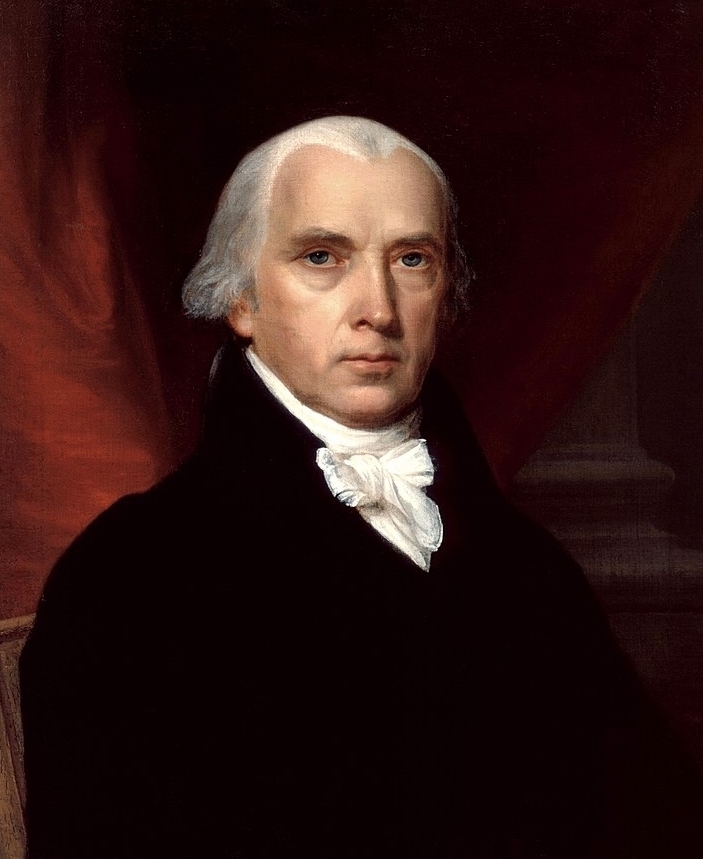

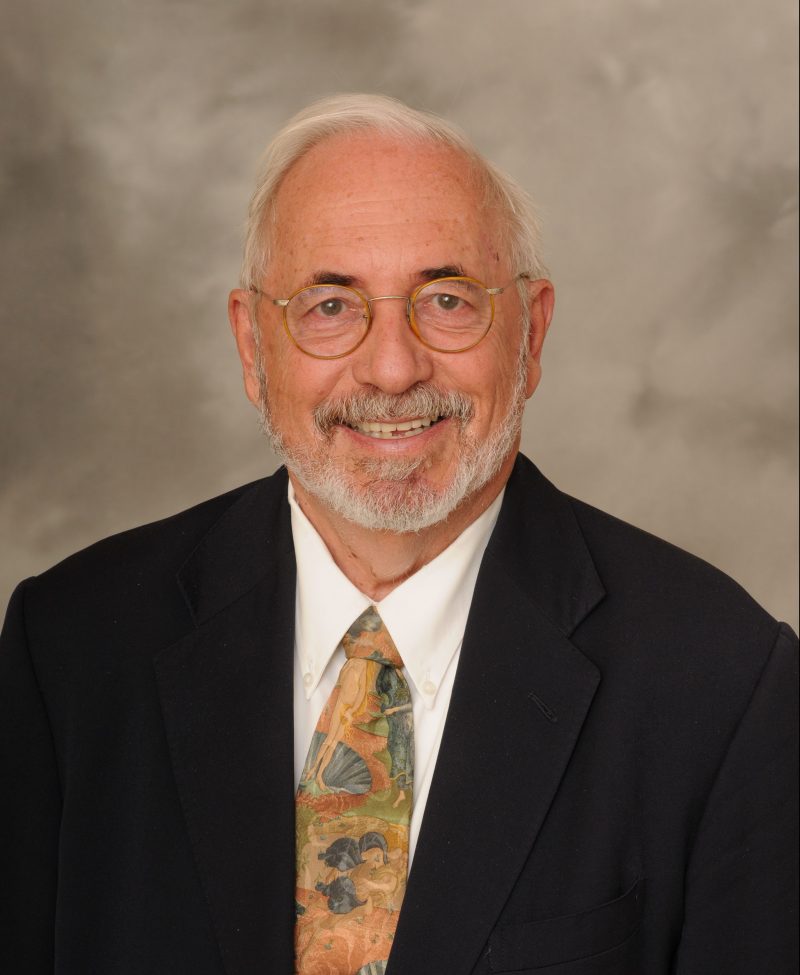

John Agresto is the former President of St. John’s College and former Chancellor and Provost of the American University of Iraq. While acting President of St. John’s, which has been praised as one of the best liberal arts colleges in the country, Professor Agresto actively worked in designing and supporting its Great Books Program. He has been a leading proponent of the value of a liberal arts education, lecturing and writing on its nature and benefits for many years. Before assuming his position at St. John’s College, Professor Agresto served as President at the Madison Center in Washington, D.C. and as Assistant Chairman, Deputy Chairman, and Acting Chairman to the National Endowment for the Humanities for seven years. Widely published in the areas of politics, law, and education, he is the author or editor of several books, including Rediscovering America: Liberty, Equality, and the Crisis of Democracy (Asahina & Wallace, 2015), Mugged by Reality: The Liberation of Iraq and the Failure of Good Intentions (Encounter, 2007), The Supreme Court and Constitutional Democracy (Cornell, 1984), and The Humanist as Citizen: Essays on the Uses of the Humanities (National Humanities Center, 1981).

John Agresto is the former President of St. John’s College and former Chancellor and Provost of the American University of Iraq. While acting President of St. John’s, which has been praised as one of the best liberal arts colleges in the country, Professor Agresto actively worked in designing and supporting its Great Books Program. He has been a leading proponent of the value of a liberal arts education, lecturing and writing on its nature and benefits for many years. Before assuming his position at St. John’s College, Professor Agresto served as President at the Madison Center in Washington, D.C. and as Assistant Chairman, Deputy Chairman, and Acting Chairman to the National Endowment for the Humanities for seven years. Widely published in the areas of politics, law, and education, he is the author or editor of several books, including Rediscovering America: Liberty, Equality, and the Crisis of Democracy (Asahina & Wallace, 2015), Mugged by Reality: The Liberation of Iraq and the Failure of Good Intentions (Encounter, 2007), The Supreme Court and Constitutional Democracy (Cornell, 1984), and The Humanist as Citizen: Essays on the Uses of the Humanities (National Humanities Center, 1981).

Professor Agresto is a JMC board member.

Learn more about John Agresto >>

![]()

![]() Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western political tradition!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western political tradition!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.