An Interview with Professor Keith Dougherty

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC partner program director Keith Dougherty. Dr. Dougherty is professor of Political Science at the University of Georgia’s School of Public & International Affairs.

In addition, Dr. Dougherty is director of the American Founding Group, which is a group of students and a couple faculty and staff which meet monthly to discuss works related to the American Founding. The following interview focuses on his article, “The Effects of the Great Compromise on the Constitutional Convention of 1787,” co-authored with Aaron Hitefield, forthcoming in American Political Research.

ED: What inspired you to become a political scientist?

KD: Throughout my career, I have always fallen sideways into something better than I had previously planned. Originally, I planned to take a job as supervisor in an assembly plant that made ice machines. Then I thought that lifestyle did not fit my personality so well, so I took a job as an admissions counselor for my alma mater instead. In that position I saw the other side of being a professor. I saw how interesting professors truly were and how flexible their lifestyles could be.

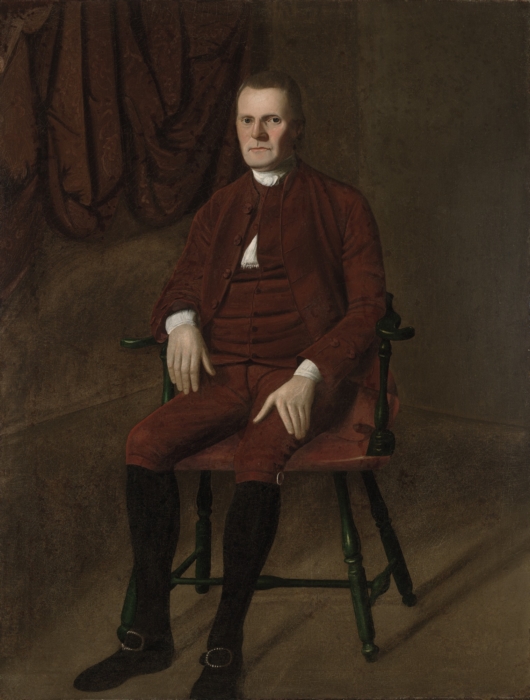

Adam Smith

John Stuart Mill

David Hume

I had a strong interest in philosophy of science and was trained in the classics of political economy – big thinkers like Adam Smith, David Hume, Karl Marx, and John Stuart Mill. Following the advice of a couple faculty, I applied to doctoral programs in philosophy, economics, and political science. I think I chose political science because I wanted to study empirical phenomena, which ruled out philosophy, and I thought political science had better cases to study than economics. For example, I thought it was more interesting to study the tactics and motivations of individuals trying to behave collectively than to study the elasticity of some product.

When I entered my doctoral program, I found that the statistical methods and formal theorizing from economics were still the best way to find answers to the big questions. At the same time, I began developing my interest in history, reading a lot on the early American period. I then found a way to combine the two. Namely, I wanted to study government under the Articles of Confederation using theories of collective action as a guide and simple tests of the theory. My goal was to use the tools of economics to study political history. It was never to replace historical narrative with something quantitative and oversimplified. Data analytics complements the work of the historian. It should never displace it.

ED: What sparked your interest in the Great Compromise?

KD: I find early American political history fascinating because early Americans achieved a lot in such a short period of time. In the late eighteenth century, Americans initiated an intellectual break from the world’s greatest superpower, Great Britain, engaged in what appeared to be a hopeless war against their mother country, and established some of the most important political institutions in the United States, such as the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. As a political scientist, I naturally studied how and why those political institutions came into being. A deep dive into the Constitutional Convention of 1787, which created our original, unamended constitution, seemed like a must.

When I was a child, someone told me that the nation had problems in the late 1780s, the states sent their best thinkers to solve the problems, and those thinkers worked together to achieve their common goals. But if you study the Constitutional Convention, you’ll realize that the delegates had very different opinions about how to address the nation’s problems, and they even had disagreements over whether there was a problem at all.

James Madison of Virginia

For example, Virginians like James Madison believed that allowing each state an equal voice in the legislature was a major flaw of the Articles of Confederation. They argued that larger states with greater populations should be given a greater voice instead. On the other hand, those representing small states, such as Roger Sherman of Connecticut or William Paterson of New Jersey, did not think equal treatment of the states was a problem. They found the large state solution objectionable.

So what became truly interesting was discovering how delegates from the small states and delegates from the large states resolved their differences and what the solution meant for the rest of their proceedings.

ED: What made the “Great Compromise,” great?

KD: James Madison thought that proportional representation would address one of the nation’s greatest problems. He also believed it was the necessary ingredient for the large states to relinquish power to the national government. States would not want to grant significant power to a new national government if other states governed its decisions. The delegates from the smaller states felt the same way, but in the opposite direction. If both chambers of the legislature were proportional, why should the small states concede power to the national government and subject themselves to control by the large states?

William Paterson of New Jersey

The question about legislative apportionment divided the convention and occupied it for roughly the first third of its proceedings. At one point, the small state delegates threatened to leave the convention if the large state delegates continued to insist on proportional representation in both chambers. Tempers flared, and it seemed like the experiment of a new national government would fail.

Roger Sherman of Connecticut, author of the Great Compromise

What made the Great Compromise, also known as the Connecticut Compromise, so great was it gave both sides a means to protect their states’ interests, even if neither side obtained everything they wanted. It offered a solution to an insurmountable problem and helped keep both sides at the convention, focused on creating their new national government. The House would be apportioned according to each state’s population, in the interest of the large states, and the Senate would be apportioned equally among the states, in the interest of the small states. This monumental agreement was passed on July 16, a little less than halfway through the convention.

ED: You write about how scholars have made three major claims about the effects of the Great Compromise. What are these claims?

Scholars have made three broad claims about the Great Compromise.

First, they claim that most of the delegates wanted a stronger national government, and they were more likely to support strengthening it after the compromise than before. The delegates just needed assurances that their state’s voice wouldn’t be lost before they openly supported it.

John Rutledge of South Carolina

Second, scholars claim that Southern delegates were more likely to support measures to weaken the national government after the compromise than before. This was because popular-based apportionment largely protected Southern interests, while equal state apportionment largely protected Northern interests. When the convention temporarily agreed that both chambers of the legislature might be proportional during the first third of the convention, Southerners supported a stronger national government. But when the Great Compromise passed, the upper chamber would be controlled by the small-Northern states, and Southern delegates found reasons to weaken the national government.

Alexander Hamilton of New York

Third, scholars claim that after the Great Compromise the large-state coalition supported strengthening the House of Representatives relative to the Senate, while the small state coalition supported strengthening the Senate relative to the House. The reason was that both coalitions wanted the most important decisions to be made in the chamber their side controlled. For example, ten days prior to the Great Compromise, all members of the small state coalition (with the exception of New York, which was divided) voted in favor of originating revenue bills in the House. After the compromise, those same states voted against a proposal with the same wording.

ED: How does your research complicate these claims about the Great Compromise?

KD: The data support some of these claims but not others. For example, two small states, Connecticut and New Jersey, were indeed more likely to support proposals to strengthen the national government after the compromise than before. But this was not true for all states, not even the small states of Delaware and Maryland. Scholars may have thought that they observed more support for a stronger national government because the convention passed more motions per day after the compromise, creating the appearance of swelling support for a strong national government, when in reality, it remained fairly constant.

The Report of the Grand Committee’s text outlining the Great Compromise of July 16, 1787

Regarding the second claim, Southern states were more likely to support weakening the national government after the compromise than before. However, the tendency may result from the small-state, large-state divide being redefined. Four of the six states in the large coalition were also from the South (Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia), and all of the Southern states, except for Maryland, were in the large state coalition. Therefore, there is considerable overlap between the Southern states and the large states. Unsurprisingly, members of the large state coalition were also more likely to support measures to weaken the national government after the compromise than before.

Finally, even though the large state coalition strengthened the House relative to the Senate after the compromise, as scholars have claimed, the small state coalition did not do the same for the Senate. The latter does seem like a natural extension of the former, but the small states were actually less likely to support strengthening the Senate after the compromise. Thus, it appears that the large states aimed to shift power in their direction after the compromise, whereas the small states were not as self-serving.

ED: You frequently cite Max Farrand’s records on the Constitutional Convention. Why is Farrand’s work such a valuable source for scholars?

KD: In order to promote candid discussions, the convention agreed not to record the votes of individual delegates. Delegates were further sworn to secrecy about the proceedings. Consequently, the official recordings of the Constitutional Convention were limited.

Historian Max Farrand

In the early twentieth century, Max Farrand went to great lengths to overcome that deficiency. He gathered all the records from the federal convention, including notes from the debates recorded by Madison, Yates, McHenry, and others. He also gathered the convention journal, letters and diaries related to the convention, along with any official documents exchanged with the states. These documents were subsequently published under the title “The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787.” James Hutson later published a supplement. Farrand’s records, along with Hutson’s supplement, constitute the most comprehensive documentation of the creation of the Constitution. They offer remarkable insights into the proceedings of the convention and have been utilized by nearly every scholar who has studied the event.

ED: Explain some of the major implications that the Great Compromise had on enslaved people.

Although the Great Compromise played a pivotal role in the Constitutional Convention, potentially contributing to the Constitution’s success in Philadelphia and its ratification by the states, equal representation in the Senate came at a price. The Constitution’s provision for equal apportionment in the Senate and the Missouri Compromise’s promise of maintaining the same number of slave and free states gave the South a veto over national laws that it maintained only because the Senate was apportioned equally. If both chambers were apportioned by free population, the North would have controlled both chambers of Congress by large margins in the 1820s, and the South would not have its veto.

A coffle of enslaved people being driven on foot from Staunton, Virginia, to Tennessee in 1850.

This change might have led to the prohibition of slavery in any new state joining the union, tests of the fugitive slave laws, and national attempts to end slavery through federal statutes before the Civil War. In other words, the bargain between the small and large states may have inadvertently perpetuated slavery and exacerbated its conditions.

ED: What has your research on the Great Compromise taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

KD: The Great Compromise underscores the importance of compromise and pragmatism in the American political tradition. Several compromises at the Constitutional Convention helped the Constitution gain enough support to be ratified by the states. The convention needed to address issues about the balance of power between large and small states, the question of slavery, and the distribution of authority between federal and state government. The Great Compromise exemplified the art of compromise. It balanced the interests of large and small states by providing proportional representation in the House and equal representation in the Senate.

The framers’ willingness to find practical solutions to complex issues such as these illustrates their pragmatism. They may have entered debates filled with philosophical ideals, but they soon recognized the need to create a workable system of government that could address the diverse interests of the states and the people within them.

The framers’ willingness to find practical solutions to complex issues such as these illustrates their pragmatism. They may have entered debates filled with philosophical ideals, but they soon recognized the need to create a workable system of government that could address the diverse interests of the states and the people within them.

Equal representation of states in the Senate fit awkwardly with a government grounded in popular sovereignty, but it was a pragmatic solution to a problem that affected both sides. It allowed the small state nationalists to support the creation of a new, stronger national government, rather than to walk out of the meetings and abandon the endeavor of creating a new government.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about the American political tradition?

KD: Every student should know that compromise played a critical role in shaping some of the most important political institutions in American history. The House and Senate owe their existence to a compromise struck between delegates representing large and small states. Similarly, the method of electing the president emerged from a compromise between delegates advocating popular election and those favoring state electors. Even the Bill of Rights stands as a testament to compromise, with Federalists consenting to its inclusion in exchange for Antifederalists’ ratification of the Constitution without amendments.

In today’s political landscape, some people believe that politicians should never compromise and should refuse to collaborate with members of the other party. However, this approach differs from the approach of the framers.

The framers of the Constitution would have sought common ground by actively engaging with the opposing side and pursuing their shared objectives. While compromise may be hard to find and can invite criticism from various quarters, it remains an integral part of the American political process. This process stands as a tribute to the framers’ unwavering commitment to the greater good of the nation over their own ideologies and personal concerns.

ED: Inspiring words, thank you for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).

Enjoyed this piece? Sign up for our newsletter to read more stories from American history!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.

![]()

![]() Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for updates about lectures, publications, podcasts, and events related to American political thought, United States history, and the Western tradition!

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.