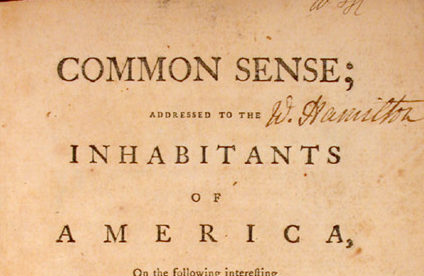

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

January 10 marks the anniversary of the publication of Thomas Paine’s influential Common Sense in 1776.

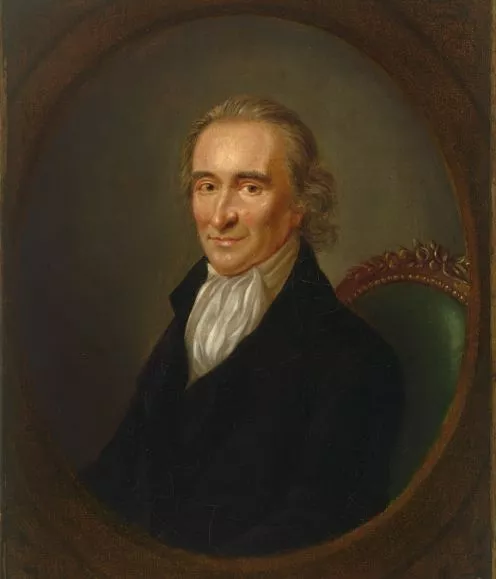

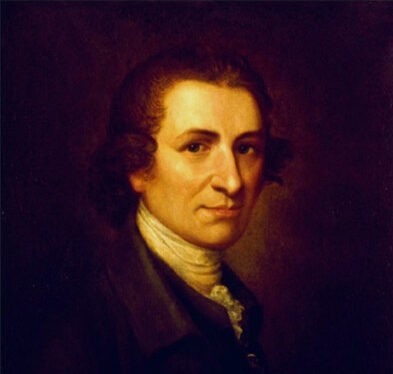

On January 10, 1776, an obscure immigrant published a small pamphlet that ignited independence in America and shifted the political landscape of the patriot movement from reform within the British imperial system to independence from it.

One hundred twenty thousand copies sold in the first three months in a nation of three million people, making Common Sense the best-selling printed work by a single author in American history up to that time.

Never before had a personally written work appealed to all classes of colonists. Never before had a pamphlet been written in an inspiring style so accessible to the “common” folk of America.

A government of our own is our natural right…Ye that oppose independence now, ye know not what ye do; ye are opening a door to eternal tyranny, by keeping vacant the seat of government.

Common Sense made a clear case for independence and directly attacked the political, economic, and ideological obstacles to achieving it. Paine relentlessly insisted that British rule was responsible for nearly every problem in colonial society and that the 1770s crisis could only be resolved by colonial independence. That goal, he maintained, could only be achieved through unified action.

Hard-nosed political logic demanded the creation of an American nation. Implicitly acknowledging the hold that tradition and deference had on the colonial mind, Paine also launched an assault on both the premises behind the British government and on the legitimacy of monarchy and hereditary power in general. Challenging the King’s paternal authority in the harshest terms, he mocked royal actions in America and declared that “even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their own families.”

Finally, Paine detailed in the most graphic, compelling and recognizable terms the suffering that the colonies had endured, reminding his readers of the torment and trauma that British policy had inflicted upon them.

Yuval Levin on the Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Right and Left

but from the errors of other nations, let us learn wisdom, and lay hold of the present opportunity—To begin government at the right end…

Resources on Thomas Paine and Common Sense

In addition to the audacity and timeliness of its ideas, Common Sense compelled the American people because it resonated with their firm belief in liberty and determined opposition to injustice. The message was powerful because it was written in relatively blunt language that colonists of different backgrounds could understand.

Paine, despite his immigrant status, was on familiar terms with the popular classes in America and the taverns, workshops, and street corners they frequented. His writing was replete with the kind of popular and religious references they readily grasped and appreciated. His strident indignation reflected the anger that was rising in the American body politic. His words united elite and popular strands of revolt, welding the Congress and the street into a common purpose.

As historian Scott Liell argues in Thomas Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to Independence: “[B]y including all of the colonists in the discussion that would determine their future, Common Sense became not just a critical step in the journey toward American independence but also an important artifact in the foundation of American democracy” (20).

Commentary and articles from JMC Scholars

Common Sense and the political thought of Thomas Paine

Seth Cotlar, “Thomas Paine in the Atlantic Historical Imagination.” (Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions, University of Virginia Press, 2013)

Seth Cotlar, Tom Paine’s America: The Rise and Fall of Trans-Atlantic Radicalism in the Early Republic. (University of Virginia Press, 2011)

Seth Cotlar, “Tom Paine’s Readers and the Making of Democratic Citizens in the Age of Revolutions.” (Thomas Paine: Common Sense for the Modern Era, San Diego State University Press, 2007)

Armin Mattes, “Paine, Jefferson, and the Modern Ideas of Democracy and the Nation.”(Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions, University of Virginia Press, 2013)

Eric Nelson, “Hebraism and the Republican Turn of 1776: A Contemporary Account of the Debate over Common Sense.” (The William and Mary Quarterly 70.4, October 2013)

Peter Onuf (editor), Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions. (University of Virginia Press, 2014)

William Parsons, “Of Monarchs and Majorities: Thomas Paine’s Problematic and Prescient Critique of the U.S. Constitution.” (Perspectives on Political Science 43.2, 2014)

Gordon Wood, “The Radicalism of Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine Considered.”(Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions, University of Virginia Press, 2013)

Michael Zuckert, “Two paths from Revolution: Jefferson, Paine and the Radicalization of Enlightenment Thought.”(Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions, University of Virginia Press, 2013)

…But where says some is the King of America? I’ll tell you Friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Britain. Yet that we may not appear to be defective even in earthly honors, let a day be solemnly set apart for proclaiming the charter; let it be brought forth placed on the divine law, the word of God; let a crown be placed thereon, by which the world may know, that so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.