Socratic political philosophy

Political philosophy

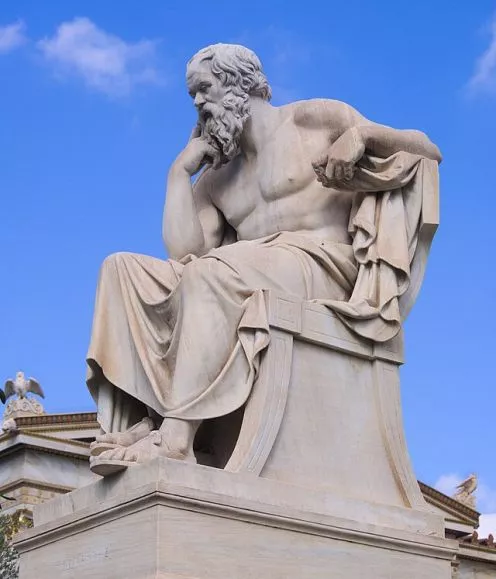

The proper place of speech, or reason, in the political community became for the first time a pressing theoretical question and political issue with the life and death of Socrates. Socrates departed from the tradition of philosophy that preceded him by, among other things, his decision to investigate moral and political questions by questioning publicly and privately the opinions of his unphilosophic contemporaries.

His public questioning of received opinion about virtue and citizenship led to his prosecution by his home city of Athens on charges of impiety and ultimately to his execution. The defense he gave in the face of these charges, memorialized in the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, may not have saved his life, but it helped to secure the privileged place of science or philosophy in the ancient regime and thereafter in the Western world.

Socrates’ defense speech, as recounted by Plato, makes arguments that would later become elements of standard defenses of freedom of speech. In Plato’s telling, Socrates argues that people cannot help believing what they believe and therefore ought to be corrected rather than punished. Accordingly, the only appropriate remedy for false or wicked teachings is a true and sound argument.

The people of Athens, however, had never given rigorous thought to how to teach citizens how to be good, or why they should be loyal to the city and its traditions. Only by permitting citizens to question these traditions is it possible for anyone to arrive at the knowledge of politics that alone can place such loyalty on solid foundations.

Socrates on philosophy and politics resources

Socrates’ approval of censorship

Since these arguments seem to point toward the principle of freedom of speech, it is striking that in other dialogues Socrates not only stops short of defending freedom of speech but even advocates against it. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates notoriously argues that the social stability necessary for his famous “city in speech” requires telling citizens a “noble lie” about their origins and their political and economic station in the city.

The education of the guardian class, moreover, involves a radical censorship program under the strict control of the philosophers who both design the regime and lead it. In Plato’s Laws, heterodox views about the city and its gods are not corrected through an open discussion of them, but through private meetings with the ominously-titled “nocturnal council.” Why does Socrates, who is so keenly aware that the pursuit of knowledge requires openness to opposing views, think it necessary not only to suppress heterodoxy but even to knowingly promote falsehoods?

Here we must confront a fundamental difference between Socratic political philosophy and the political philosophy of the Enlightenment that informs modern, rights-based government and that led to the adoption of the political principle of free speech. Enlightenment political philosophers entertained far greater hopes than Socrates and his students of making rationality widespread. Socrates’ doubts about his ability to educate citizens en masse is made somewhat more clear in Xenophon’s account of Socrates’ trial than in Plato’s. Xenophon argues that Socrates not only did not think that an honest account of his merit would save him from execution, but even hoped that it would ensure his execution and save him from the decline of old age.

In other words, Socrates did not think that most people could be brought to see things philosophically by public argument; the most philosophers can hope to accomplish is to educate a very few outstanding students to philosophy and perhaps instill some measure of respect for philosophy among the rest. This view is also suggested by the Republic, which depicts the rational city as being governed by one or only a few philosopher-kings—not as being filled with rational citizens. Even in the rational city, reason belongs only to a privileged few.

Socrates and freedom of speech resources

Deeper doubts about reason and politics

As serious as these doubts about the possibility of enlightenment may be, Plato’s Apology may indicate even graver doubts about the possibility of rational politics. While Socrates does argue there that correction through free inquiry is the only way one could hope to arrive at a true civic education, he does not say that such an education is possible. In fact, Socrates famously argues that what his investigations have established firmly is only that no one, himself included, possesses the knowledge of virtue that could be the foundation of such an education.

There are many ways to interpret Socrates’ bold statement of his own ignorance, but what is clear is that while Socrates understood it to be possible to rationally defend the pursuit of moral and political wisdom, he did not think that such wisdom was available at his time. Nor did he seem to think that progress toward that kind of wisdom was possible, except in the limited sense that an awareness of one’s ignorance is a kind of progress.

It would seem, then, that Socrates perceived a problem with the opinions or judgments that inform every political community and that this perception led him eventually to conclude that the only sound political principle, or principle of action, is to whole-heartedly pursue wisdom. In other words, one should live a life of philosophy instead of devoting oneself to the improvement of the city. For Socrates, therefore, the judgments of citizens—even elite citizens—cannot possibly rise to the level of knowledge without losing their distinctly political character. This conclusion implies that political disputes about these judgments, insofar as they are political, will never be truly free and open—that is to say, they will never be philosophic or scientific. Any law or edict establishing the freedom of speech and unrestricted inquiry will only ever be an artificial and confused image of the true or natural principle of philosophic inquiry.