Abraham Lincoln and the Preservation of the Union

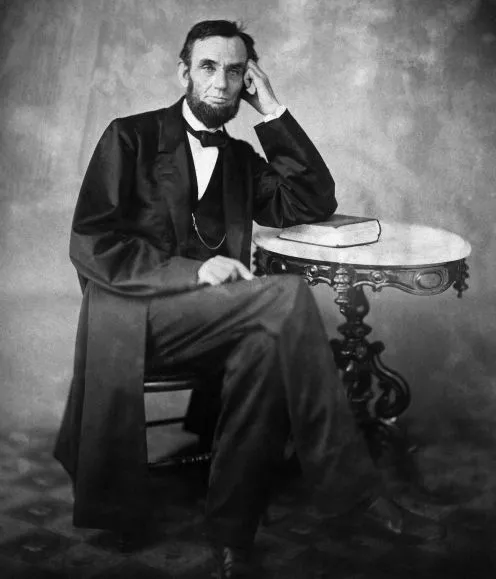

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809 near Hodgenville, Kentucky. He is best known for his immense impact in leading our nation through a civil war and for ultimately abolishing slavery.

Abraham Lincoln was born near Hodgenville, Kentucky, on February 12, 1809 to a farmer, Thomas Lincoln, and his wife, Nancy (née. Hanks) Lincoln. Though he had limited access to education, young Lincoln read extensively when not working on the family farm. In early adulthood, he worked on a flatboat transporting produce on the Mississippi River, as a store clerk, postmaster, and surveyor. Ambitious and likeable, he was elected to the Illinois legislature in 1834, studied for and passed the bar exam in 1836, and began practicing law in 1837.

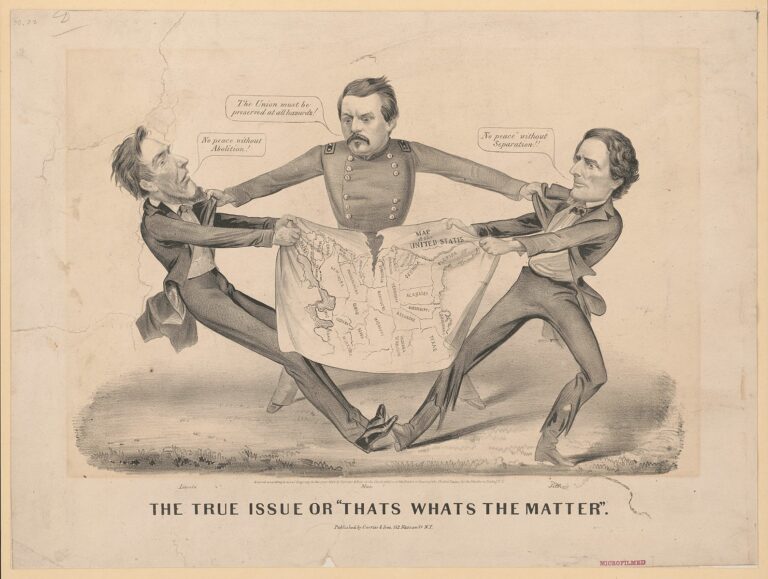

Lincoln ran for and won a seat in Congress as a Whig in 1846, but did not enter the national stage until 1858, when he ran against Stephen Douglas for a Senate seat. Although Lincoln lost this election, he gained fame for his articulate positions on slavery and states’ rights in the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and subsequently won the Republican presidential nomination. Without the support of even one southern state, he won the presidency in the election of 1860. Southern secession began soon after, leaving Lincoln with one of the greatest challenges faced by the United States: reunification.

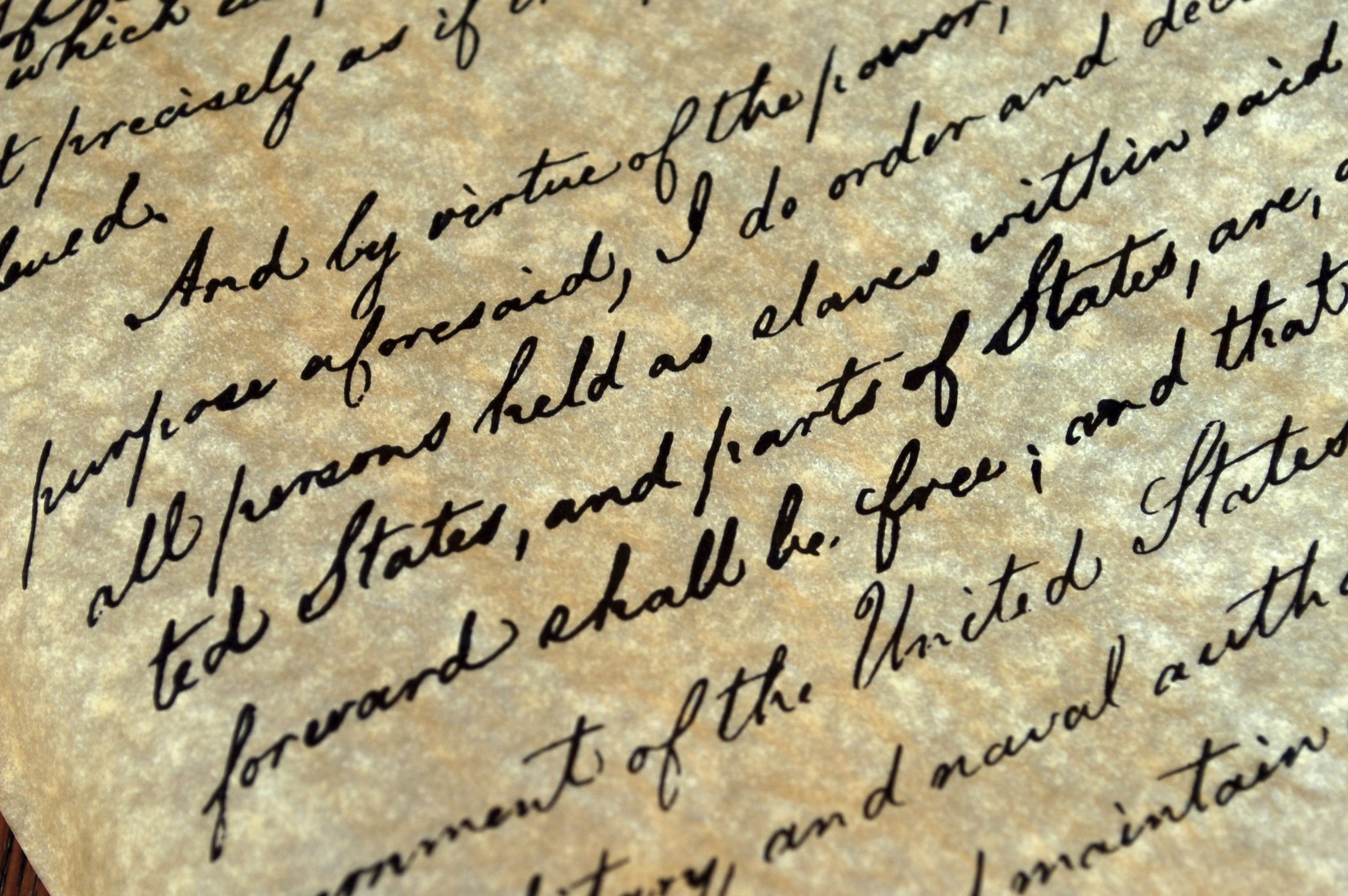

In his first term as president, Lincoln made the difficult decision to declare war on the seceded southern states. On January 1, 1863, he released his famous Emancipation Proclamation, which abolished slavery in the United States. Although the Proclamation didn’t take effect in the South until after the war, it was a significant step towards liberty and pinpointed the meaning of the war: not just reunification of the states, but the end of American slavery.

The Civil War did not start off well – Lincoln struggled to find competent generals, and public support fluctuated. The turning point of the war is still debated among scholars today, but an increase in Union military victories and Lincoln’s reelection are often credited to the appointment of Ulysses S. Grant and the success of Sherman’s March. The war ended in April 1865. Sadly, Lincoln did not have time to enjoy peace or work towards Reconstruction. He was assassinated on April 14, 1865 in Ford’s Theatre, less than a week after Lee’s surrender.

“…Passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy. Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defence.–Let those materials be moulded into general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws: and, that we improved to the last; that we remained free to the last; that we revered his name to the last; that, during his long sleep, we permitted no hostile foot to pass over or desecrate his resting place; shall be that which to learn the last trump shall awaken our WASHINGTON.

Upon these let the proud fabric of freedom rest, as the rock of its basis; and as truly as has been said of the only greater institution, ‘the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.’”

Jack Miller Center’s historical series on Abraham Lincoln

As part of of JMC’s weekly newsletters (packed full of historical stories, news on campus programming, and Center updates), we ran a series on Abraham Lincoln and his lasting legacy. Access Parts I, II, and III below

Part I: Lincoln’s Leadership in the Face of Defiance, Secession, and His Constitutional Oath

“A couple weeks ago, we examined the infamous legacy of Lincoln’s predecessor, President James Buchanan.

Often remembered for his weak attempts to pacify the nation and avoid war, his inaction only strengthened slavery’s foothold and inflamed divisions further.

But what was Lincoln’s role? Did Lincoln push the nation to war, as some at the time suggested? Or was it an unavoidable consequence of persistent southern defiance and the deepening threat of the Union dissolving?…”

Part II: Fighting to Realize Our Founding Principles: The Emancipation Proclamation and the Start of Slavery’s End

“We often associate the Civil War with the end of slavery — and for good reason.

But Lincoln’s primary goal in going to war was to save the Union, slavery or not. The Emancipation Proclamation changed the equation.

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861. Though Lincoln morally opposed slavery, he avoided any public comments connecting the war and the rights of slaves. He was concerned more with acting constitutionally and a swift victory to prevent the Union from dissolving…”

Part III: The Gettysburg Address, Lincoln’s Legacy, and the Pursuit of Liberty and Equality

“In the small battle-torn town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on November 19, 1863, Lincoln uttered 266 words that would be remembered as one of the greatest American speeches of all time. In a time of mourning for the many who died, his Gettysburg Address proclaimed our national purpose and served as a rallying cry to defend it—the carnage of the war should not be in vain.

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth…”

Selected online resources on Abraham Lincoln

If you are a JMC Scholar who’s published on the Abraham Lincoln or his political thought and would like your work included here

Contact UsCommentary and articles from JMC Scholars

Abraham Lincoln: Statesmanship and a Country Divided

Matthew Brogdon, “Young Mr. Lincoln in Ford’s Theater.” (Perspectives on Politics47.2, April 1, 2018)

Nicholas Buccola (editor), Abraham Lincoln and Liberal Democracy. (University of Kansas Press, 2016)

Michael Douma (co-author), “The Danish St. Croix Project: Revisiting the Lincoln Colonization Program with Foreign-Language Sources.” (American Nineteenth Century History 15.3, 2014)

Michael Douma, “The Lincoln Administration’s Negotiations to Colonize African Americans in Dutch Suriname.” (Civil War History 61.2, June 2015)

Justin Dyer, “Lincolnian Natural Right, Dred Scott, and the Jurisprudence of John McLean.” (Polity 41.1, January 2009)

Justin Dyer, “Lincoln’s House Divided and Ours.” (Starting Points Journal, December 4, 2020)

Robert Faulkner, “Lincoln and the Constitution.” (The Revival of Constitutionalism, University of Nebraska Press, 1988)

Robert Faulkner, “Lincoln and the Rebirth of Liberal Democracy.” (Journal of Supreme Court History 35.3, November 2010)

Allen Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln as a Man of Ideas. (Southern Illinois University Press, 2009)

Allen Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President. (Wm.B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1999)

Allen Guelzo, Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America. (Simon & Schuster, 2008)

Allen Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. (Simon & Shuster, 2004)

Allen Guelzo (editor), Lincoln: An Intimate Portrait. (TimeLife Books, 2014)

Allen Guelzo (editor), Lincoln Speeches. (Penguin USA, 2012)

Allen Guelzo, Lincoln: A Very Short Introduction. (Oxford University Press, 2009)

Allen Guelzo, “On Abraham Lincoln.” (National Review, July 9, 2020)

Allen Guelzo, Redeeming the Great Emancipator. (Harvard University Press, 2016)

Benjamin Kleinerman, The Discretionary President. (University Press of Kansas, 2009)

Benjamin Kleinerman, “Lincoln’s Example: Executive Power and the Survival of Constitutionalism.” (Perspectives on Politics 3.4, December 2005)

Benjamin Kleinerman, “The Show Must Go On: Why didn’t Lincoln try to postpone the 1864 election?” (The Bulwark, August 1, 2020)

Andrew F. Lang, A Contest of Civilizations: Exposing the Crisis of American Exceptionalism in the Civil War Era. (University of North Carolina Press, 2021)

Rafael Major, “Those that Have the Power to Hurt and Will Do None: Shakespearean Dimensions of Lincoln’s Statesmanship.” (Perspectives on Political Science 41.2, 2012)

John Sexton, “On Lincoln’s ‘Pragmatism.’“ (American Political Thought, 2.1, Spring 2013)

David Siemers, “Principled Pragmatism: Abraham Lincoln’s Method of Political Analysis.” (Presidential Studies Quarterly 34.4, December 2004)

Rogers Smith, “Lincoln and Obama: Two Visions of American Civic Union.”(Representation and Citizenship, Wayne State University Press, 2016)

Rogers Smith (co-author), Still a House Divided: Race and Politics in Obama’s America. (Princeton University Press, 2011)

Steven Smith, “Abraham Lincoln’s Kantian Republic.” Abraham Lincoln and Liberal Democracy, (University of Kansas Press, 2016)

Steven Smith, “Lincoln and the Politics of the ‘Towering Genius.’” (American Political Thought 7.3, Summer 2018)

Steven Smith, “Lincoln’s Constitutional Leadership.” (National Affairs 13, Fall 2012)

Steven Smith, “Lincoln’s Enlightenment.” (Principle and Prudence in the Western Political Thought, State University of New York Press, 2016)

Steven Smith, “Why Did Lincoln Go to War?” (The Political Thought of the Civil War, University of Kansas Press, 2018)

Steven Smith (editor), The Writings of Abraham Lincoln. (Yale University Press, 2012)

Gregory Weiner, Old Whigs: Burke, Lincoln, & the Politics of Prudence. (Encounter Books, 2019)

Gregory Weiner, “Of Prudence and Principle: Reflections on Lincoln’s Second Inaugural at 150.” (Society 52.6, 2015)

Gregory Weiner, “Prudence as Excellence: Edmund Burke, Abraham Lincoln and the Problem of Greatness.” (The Imaginative Conservative, April 1, 2013)

Thomas West, “Jaffa’s Lincolnian Defense of the Founding.” (Interpretation 28, Spring 2001)

Jonathan White, “155 Years Ago: Lincoln and the Black Delegation.” (The Lincoln Forum Bulletin 42, Fall 2017)

Jonathan White, Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman. (Louisiana State University Press, 2011)

Jonathan White, “Black Lives Certainly Mattered to Abraham Lincoln.”(Smithsonian Magazine, February 10, 2021)

Jonathan White, “A Black Soldier from Charlottesville Writes to Lincoln.” (University of Virginia’s John L. Nau III Civil War Center Blog, September 30, 2016)

Jonathan White, “Did Lincoln Dream He Died?“ (For the People: Newsletter of the Abraham Lincoln Association 16, Fall 2014)

Jonathan White, Emancipation, the Union Army, and the Reelection of Abraham Lincoln. (Louisiana State University Press, 2014)

Jonathan White, “‘For My Part I Don’t Care Who is Elected President’: The Union Army and the Elections of 1864.” (This Distracted and Anarchical People: New Answers for Old Questions about the Civil War-Era North, Fordham University Press, 2013)

Jonathan White, “The ‘Good and Kind’ Heart of Lincoln.” (New Jersey Monthly 37, January 16, 2012)

Jonathan White, “How Lincoln Won the Soldier Vote.” (New York Times “Disunion,”, November 7, 2014)

Jonathan White, “The Lincoln Administration and the Supreme Court during the Civil War: A Letter from Attorney General Edward Bates.” (Journal of Supreme Court History 37.3, November 2012)

Jonathan White, Lincoln on Law, Leadership, and Life. (Sourcebooks, 2015)

Jonathan White, “Lincoln’s Other Habeas Corpus Problem.” (Ex parte Merryman: Two Commemorations, Library Company of the Baltimore Bar, 2011)

Jonathan White, “The Presidential Pardon Records of the Lincoln Administration.”(Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 39.2, Summer 2018)

Jonathan White, “President Lincoln and the Sleeping Sentinel: A Story of Civil War Redemption.” (The Lincoln Forum Bulletin 40, Fall 2016)

Jonathan White, “The Soldier Vote of 1864 and the Expansion of Suffrage.” (The Lincoln Forum Bulletin 36, Fall 2014)

Jonathan White, “Why It Makes Sense to Pair Lincoln and Nelson Mandela.”(Time.com, April 15, 2015)

Michael Zuckert, “Lincoln and the Problem of Civil Religion.” (Lincoln’s American Dream, Potomac Books, 2006)

Michael Zuckert, “The Peak of American Political Religion: Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address.” (The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Religion and Politics in the U.S., Wiley-Blackwell, 2016)

Michael Zuckert, “Providentialism and Politics: Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address and the Problem of Democracy.” (Abraham Lincoln and Liberal Democracy, University Press of Kansas, 2016)