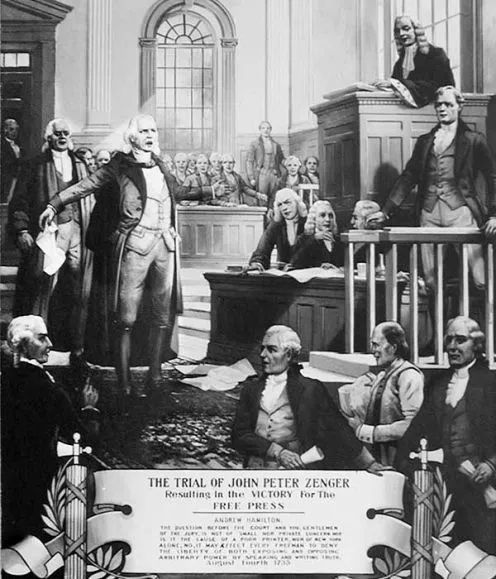

Trial of John Peter Zenger

John Peter Zenger was a printer and journalist acquitted in charges of seditious libel under the British colonial government. The trial paved the way for American commitment to the freedom of the press.

The trial and acquittal of New Yorker John Peter Zenger in 1735 on charges of seditious libel under the British colonial government became a symbol of the American commitment to the freedom of the press. It also informed many Americans’ understanding of that freedom when it was established in the bill of rights. Zenger was arrested in 1733 for publishing The New York Weekly Journal, a newspaper that was consistently critical of the colonial governor of New York, William Cosby. Zenger’s counsel argued, contrary to the common law standard of seditious libel, that the truth of his newspaper’s claims should be considered as grounds for his defense. Despite the colonial judge’s firm instructions to the jury that their duty was to decide only whether he had in fact published the essays in question, the jury acquitted Zenger in a bold act of “jury nullification.”

Primary sources on the trial

Commentary on the trial

The commentaries offer an easy-to read summary of the trial, its background, its arguments, and its legacy. They also examine the implications of the Zenger trial — in particular its example of jury nullification — for the role of the public in guarding the freedom of the press