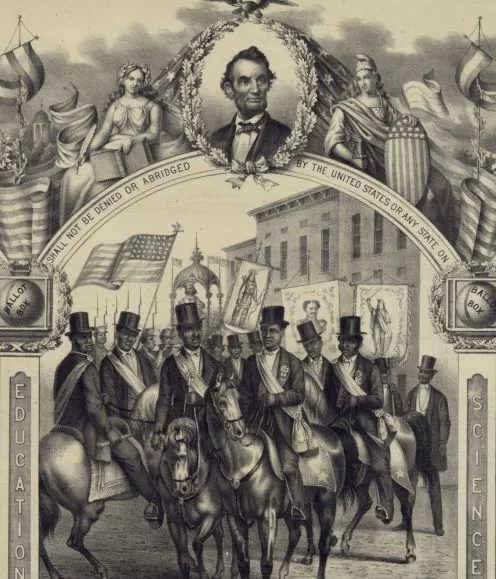

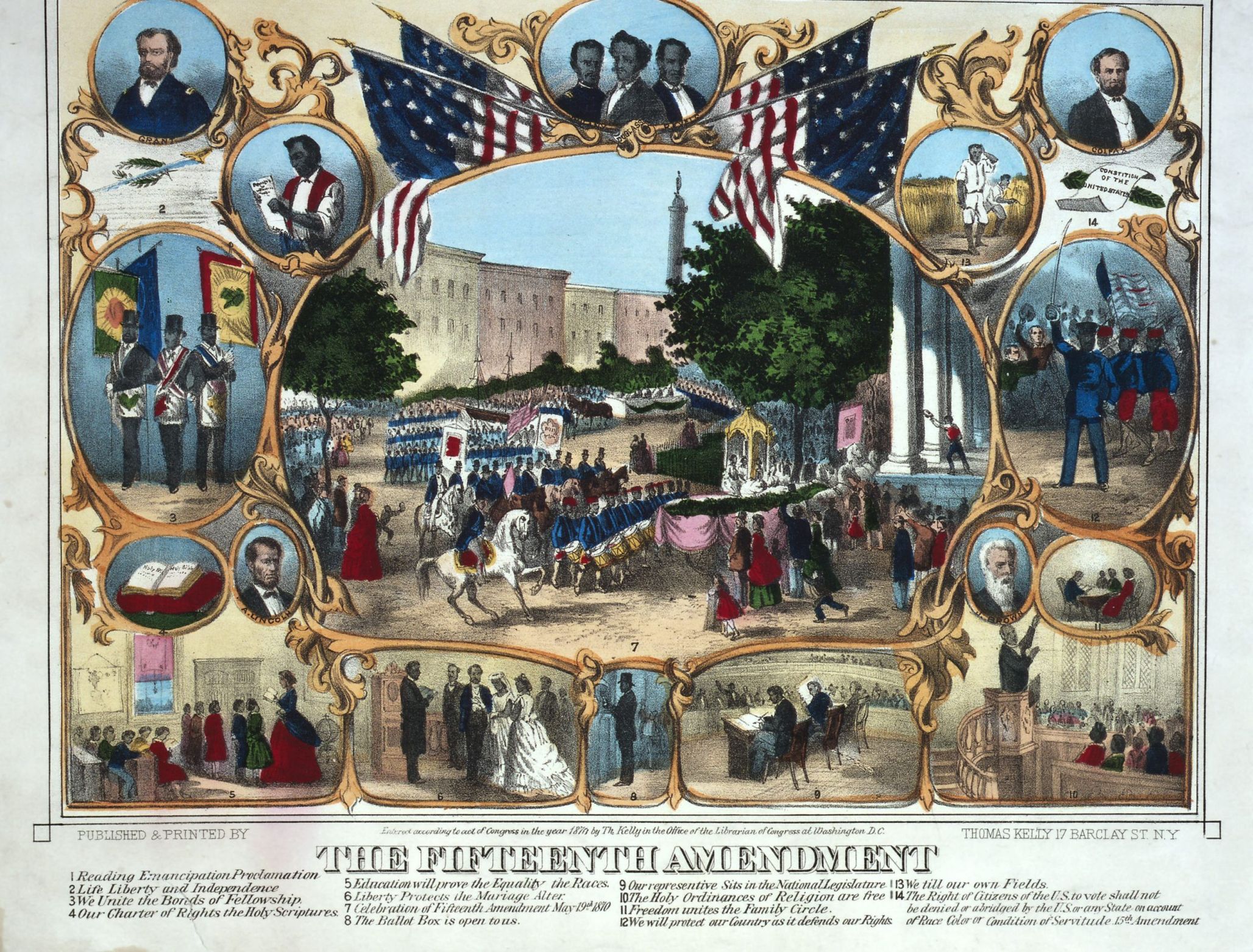

The Fifteenth Amendment

The Fifteenth Amendment was ratified on February 3, 1870.

To vote regardless of race

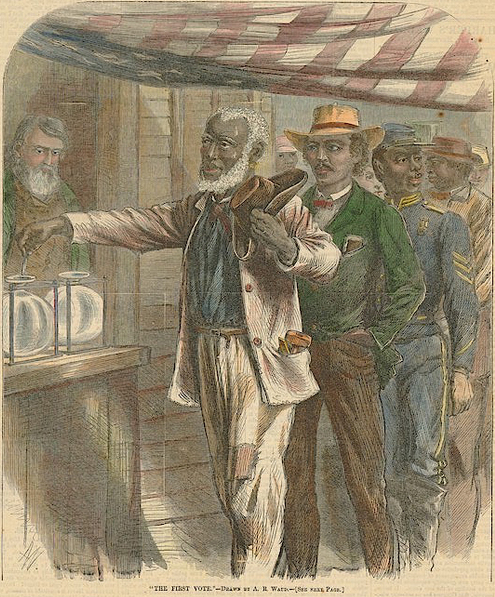

The last of the “Reconstruction Amendments,” the Fifteenth Amendment banned the denial or abridgment of suffrage based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude. It effectively gave African-American men the right to vote.

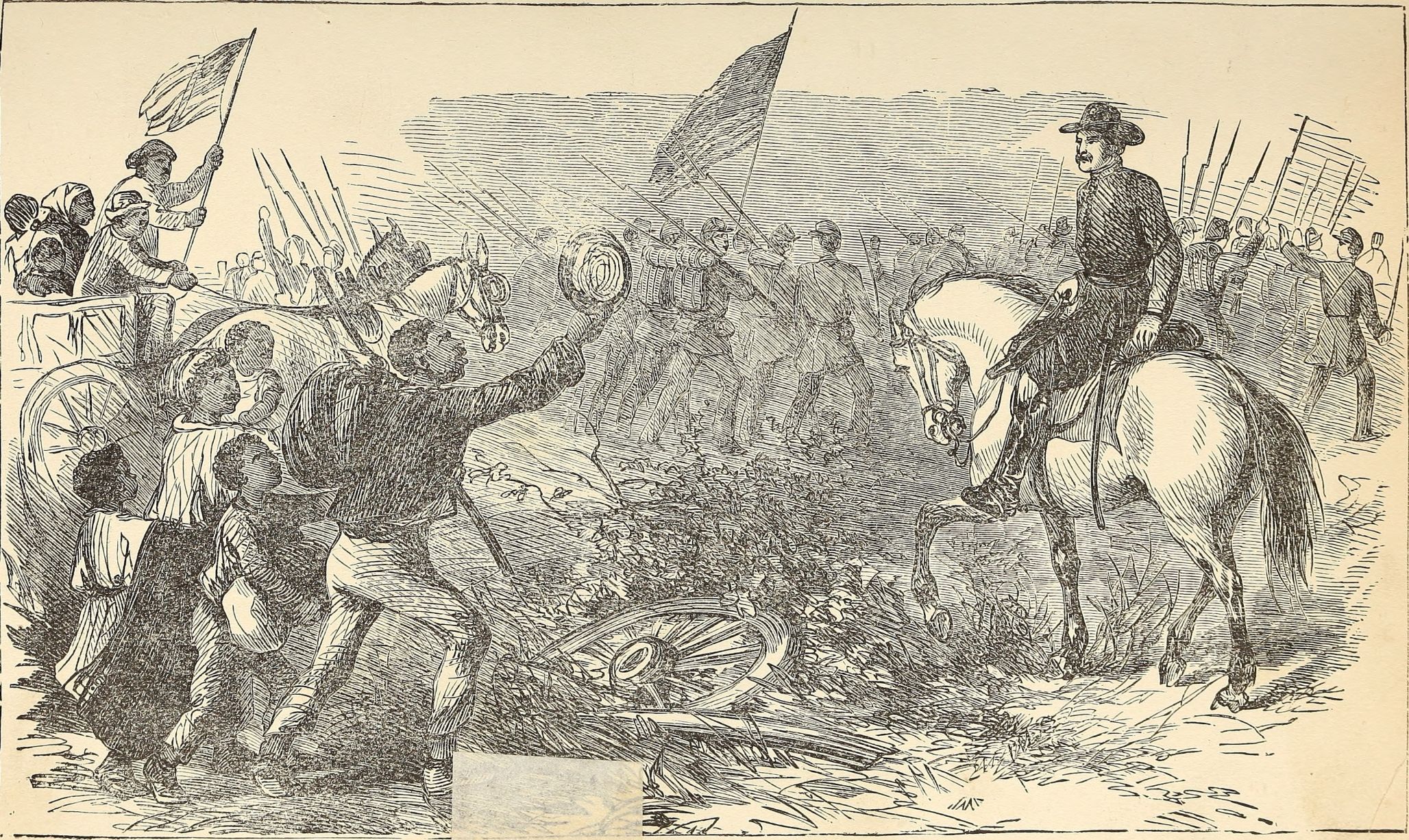

The immediate effects of the Fifteenth Amendment were dramatic. Throughout the South, thousands of African Americans registered to vote. The majority in many areas, they gained substantial political power and soon thereafter began serving as local, state, and federal representatives.

Sadly, this right of suffrage would not remain protected. As federal troops pulled out of the southern U.S. in the late 1870s, many former Confederates found ways to prevent black men from voting. African Americans faced poll taxes, literacy tests, and outright voter intimidation from white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan.

The Fifteenth Amendment, though a landmark in our constitutional history, wouldn’t be enforced again in the South for years to come when additional laws were passed during the civil rights movement.

Resources on the Fifteenth Amendment

A collection of resources recognizing this important piece of American law.

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Relevant topics

Free speech and slavery

As the country grew more divided over the question of slavery in the early 19th century and as the threat of secession by the slave states in the South loomed larger over the political landscape, efforts were made in both the South and the North to suppress the slavery issue.

Many southern states radically regulated the press, preventing the dissemination of anti-slavery literature. Since at this time, the Bill of Rights was understood to apply only to the federal government, there was no constitutional question about such measures. However, much of the anti-slavery literature in slave states was being introduced by northern abolitionists through the federal postal system. In response, southern states mandated that their post-masters refrain from delivering anti-slavery materials. Many northern states tolerated these measures either out of support for slavery or out of fear of secession.

Congress eventually supported the effort to quarantine the South from anti-slavery agitation with the Post Office Act of 1836, which permitted post-masters to respect local censorship laws. Though this was a federal law and therefore was subject to the First Amendment, it was never brought to the Supreme Court.

Primary documents

- Frederick Douglas was a former slave who became a leader in the abolitionist movement in the North after escaping from slavery in 1838. His speech below, delivered shortly before the Civil War broke out, illustrates the danger that abolitionists were in, not from overbearing government, but from mob violence. The text is from the National Constitution Center website.

- The American Anti-Slavery Society was responsible for the first direct mail campaign in U.S. history. In the same year that this declaration of principles and constitution of its organization was published, the AAS sent a shipment of abolitionist literature to a selection of southern leaders. The shipment was seized in Charleston, South Carolina by a group called the “Lynch Men,” and was burned before an angry mob of Southerners. In the wake of this event, southern states began passing laws requiring anti-slavery literature to be seized and destroyed. Read the AAS document at Teaching American History.

Commentary

- Kersch, Kenneth I. Freedom of Speech: Rights and Liberties Under the Law

- Curtis, Michael K. Free Speech, The People’s Darling Privilege”: Struggles For Freedom Of Expression In American History.

- Curtis, Michael K. “The Curious History Of Attempts To Suppress Antislavery Speech,

Press, And Petition In 1835-37.” - Graber, Mark. “Antebellum Perspectives On Free Speech.

Black history and African American political thought

African Americans have made a lasting impact on the United States and our nation’s history. Figures such as Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr. are well remembered today for their insights and political thought. In honor of black history and the contributions that African Americans have made to our country, JMC presents a collection of fellows’ articles and other resources on African-American history and political thought.

Learn more about black history and African American political thought from JMC Scholars and Founding Civic Initiative Faculty Diana Schaub, Lucas Morel, and Nicholas Buccola.

The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

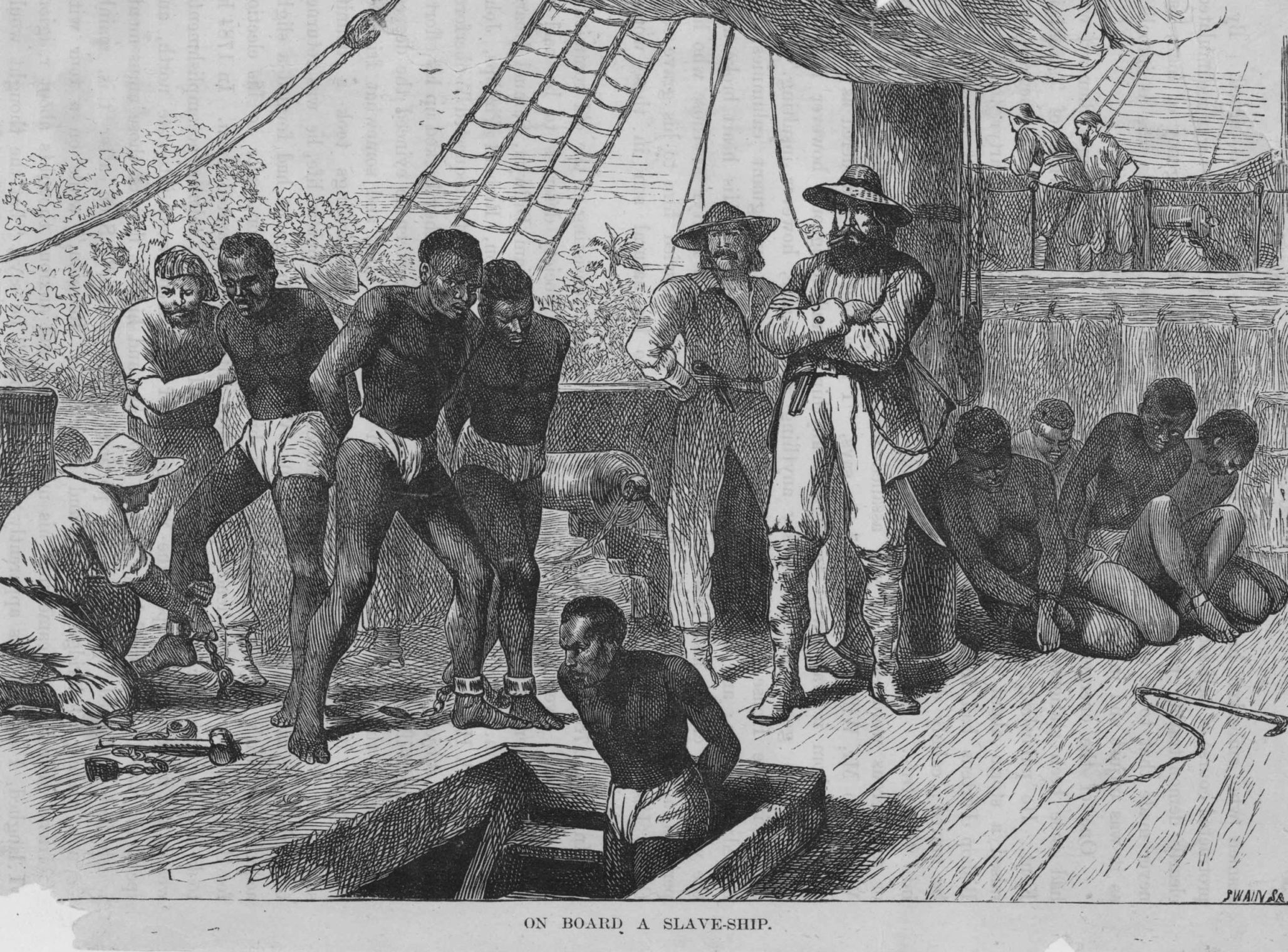

The Thirteenth Amendment

The Thirteenth Amendment was ratified on December 6, 1865. In the aftermath of the Civil War, this amendment banned slavery in the United States, ending a barbaric system that had been legal in America for well over a hundred years. Four million people, an entire eighth of the U.S. population, were freed as a result. Though the Thirteenth Amendment banned slavery in the United States, it did not give citizenship to African Americans, nor did it give African American men the right to vote. These gains were not accomplished until the passage of the other Reconstruction amendments, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, in 1868 and 1870, respectively.

The Fourteenth Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified a few years after the Thirteenth, on July 9, 1868. The amendment granted citizenship to those born or naturalized in the United States and guaranteed freedom, due process, and equal protection under the law to all Americans. In doing so, it expanded the scope of the Constitution’s protection of individual liberty; now the Constitution protected rights not only from infringement by the federal government but from infringement by state and local governments as well.

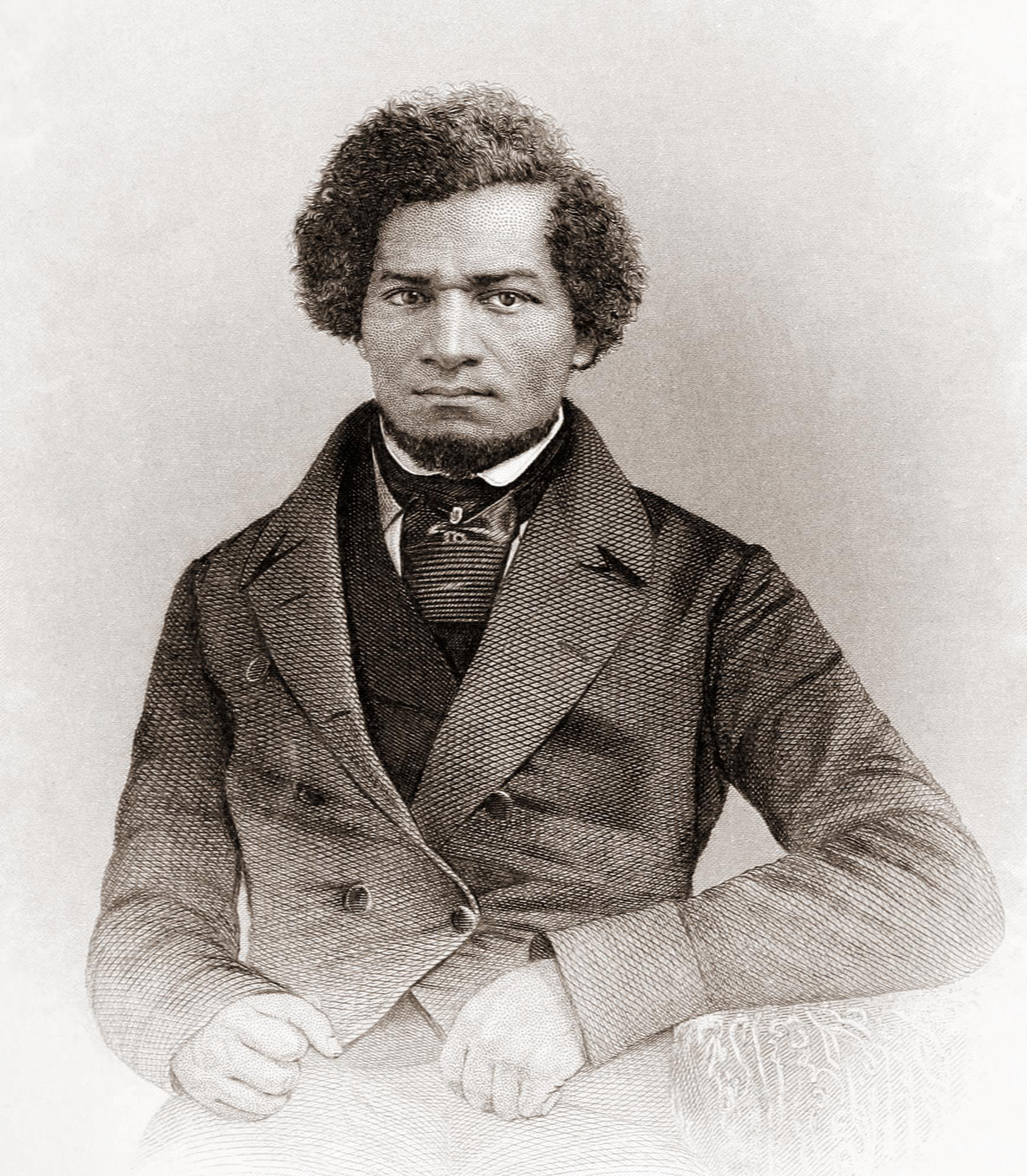

Frederick Douglass and 19th-Century Political Thought

Frederick Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in February 1818. Born a slave, Douglass only saw his mother a handful of times and never knew his father, who was white. At the age of 8, Douglass was hired out as a servant in Baltimore. While there, he taught himself to read and studied natural rights, debate, and historical speeches.

Douglass was one of America’s foremost intellectuals and greatest figures in the American antislavery movement. Douglass told the story of his escape from slavery and his arguments against that “hateful thing” were some of the most persuasive of the time. Douglass’s impressive oratory skills sent him to the national stage, where he influenced other American contemporaries such as Abraham Lincoln, William Lloyd Garrison, and John Brown.

He believed the Founding principles if applied as intended, would uphold freedom for every person: “In that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing [slavery]; but interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT.”

In his famous “Self-Made Men” lecture, Douglass emphasized the significance of self-dependence. Douglass’s faith in self-sufficiency was underscored by his belief in the American tradition of liberty through self-government.

Commentary and articles from JMC Scholars

Slavery, political philosophy, and constitutional law

William Allen, Re-Thinking Uncle Tom: The Political Philosophy of H. B. Stowe. (Lexington Books, 2008)

Mark Boonshoft, “Doughfaces at the Founding: Federalists, Anti-Federalists, Slavery, and the Ratification of the Constitution in New York.” (New York History 93.3, Summer 2012)

Justin Dyer, Natural Law and the Antislavery Constitutional Tradition. (Cambridge University Press, 2012)

Justin Dyer, “Revisiting Dred Scott: Prudence, Providence, and the Limits of Constitutional Statesmanship.” (Perspectives on Political Science39.3, 2010)

Justin Dyer, Slavery, Abortion, and the Politics of Constitutional Meaning. (Cambridge University Press, 2013)

Justin Dyer, “Slavery and the Magna Carta in the Development of Anglo-American Constitutionalism.” (PS: Political Science and Politics 43.3, July 2010)

Eliga Gould, “The Laws of War and Peace: Legitimating Slavery in the Age of the American Revolution.” (State and Citizen: British America and the Early United States, University of Virginia Press, 2013)

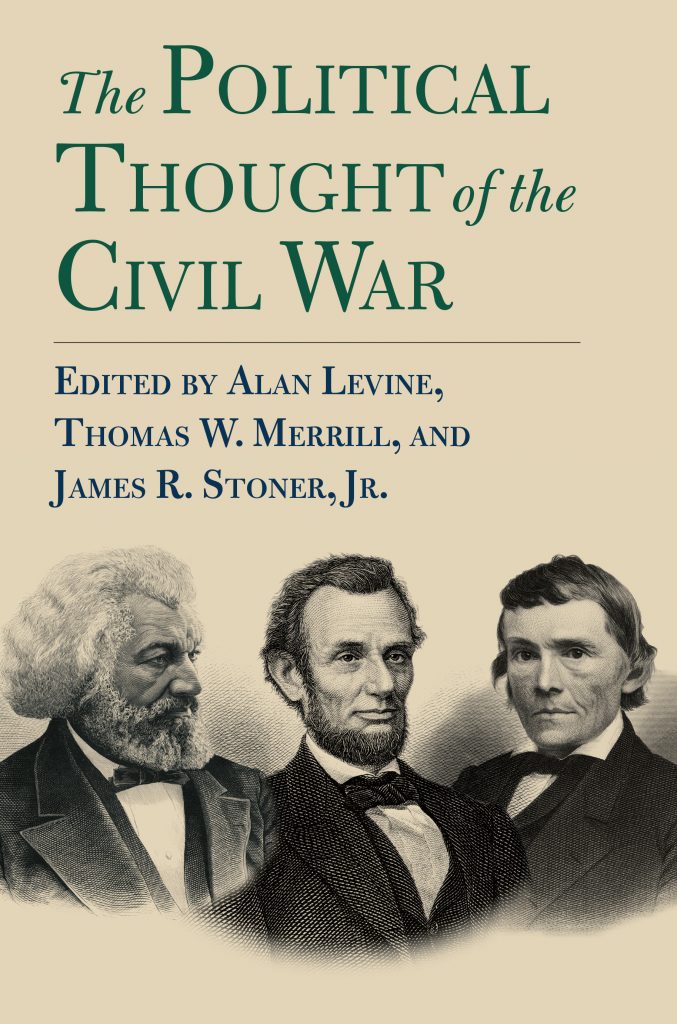

Edited by Alan Levine, Thomas Merril, and James Stoner; The Political Thought of the Civil War. (University Press of Kansas, 2018)

Peter Onuf, Statehood and Union: A History of the Northwest Ordinance. (Indiana University Press, 1987)

Justin Lawrence Simard, “Slavery’s Legalism: Lawyers and the Commercial Routine of Slavery.” (Law and History Review 37.2, May 2019)

Keith Whittington, “The Road Not Taken: Dred Scott, Constitutional Law, and Political Questions.” (Journal of Politics 63.2, May 2001)

Keith Whittington, “Slavery and the U.S. Supreme Court.” (The Political Thought of the Civil War, University Press of Kansas, 2018)

Jean Yarbrough, “Race and the Moral Foundation of the American Republic: Another Look at the Declaration and the Notes on Virginia.” (The Journal of Politics 53.1, February 1991)

Michael Zuckert, Transcript of the 2013 Walter Berns Constitution Day Lecture: Slavery and the Constitutional Convention. (American Enterprise Institute, September 17, 2013)

The Impact of the Fifteenth Amendment

Commentary and articles from JMC Scholars

Commentary and articles from JMC Scholars

Reconstruction

Michael Douma (co-author), “The Danish St. Croix Project: Revisiting the Lincoln Colonization Program with Foreign-Language Sources.”(American Nineteenth Century History15.3, 2014)

Michael Douma, “Holland’s Plan for America’s Slaves.” (New York Times, July 11, 2013)

Michael Douma, “The Lincoln Administration’s Negotiations to Colonize African Americans in Dutch Suriname.” (Civil War History 61.2, June 2015)

Allen Guelzo, “The History of Reconstruction’s Third Phase.” (History News Network, February 4, 2018)

James Patterson, “Free Markets, Racial Equality, and Southern Prosperity: The Rise and Fall of Lewis Harvie Blair.” (Library of Law and Liberty, November 21, 2014)

Diana Schaub, “Lincoln and the Other Washington.”(Law & Liberty, February 15, 2016)

Rogers Smith, “Legitimating Reconstruction: The Limits of Legalism.” (Yale Law Journal 108, 1999)

Kyle Volk, “Desegregating New York City: The Amazing pre-Civil War History of the Public Transit Integration in the North.” (Salon.com, August 10, 2014)

Michael Zuckert, “Fundamental Rights, the Supreme Court and American Constitutionalism: The Lessons of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.” (The Supreme Court and American Constitutionalism, Rowman & Littlefield, 1997)

Michael Zuckert, “Natural Rights and the Post Civil War Amendments.” (Witherspoon Institute’s Natural Law, Natural Rights and American Constitutionalism, Online Resource Center, 2009)

Voting Rights

Gideon Cohn-Postar, “Mississippi: African-American Voters Sue Over Election Law Rooted in the State’s Racist Past.” (The Conversation, September 23, 2019)

Gideon Cohn-Postar, “Mississippi Governor’s Race Taking Place Under Jim Crow-era Rules After Judge Refuses to Block Them.” (The Conversation, November 1, 2019)

Rogers Smith (co-author), “The Last Stand? Shelby County v. Holder and White Political Power in Modern America.” (Du Bois Review 13.1, Spring 2016)

Rogers Smith (co-author), “Racial Inequality and the Weakening of Voting Rights in America.” (Discover Society 33, June 1, 2016)

Rogers Smith (co-author), “Restricting Voting Rights in Modern America.” (Transatlantica 1, 2015)

Joey Torres, “The Voting Rights Act’s Pre-Clearance Provisions: The Experience of Native Americans in South Dakota.” (American Indian Culture and Research Journal 41.4, 2017)

Justin Wert (co-author), The Rise and Fall of the Voting Rights Act. (University of Oklahoma Press, 2016)

Jonathan White, “Canvassing the Troops: The Federal Government and the Soldiers’ Right to Vote.” (Civil War History 50.3, 2004)

Jonathan White, “Supporting the Troops: The Soldiers’ Right to Vote in Civil War Pennsylvania.”(Pennsylvania Heritage, Winter 2006)