Every vote matters

Americans today understand the saying, “every vote matters.”

A measure of grander importance

Whether affected by hanging-chads, butterfly ballots, or razor-thin vote counts, every vote matters because it allows one to exercise citizenship. But what did “every vote matters,” voting, and citizenship mean in the early history of the United States?

Unlike today’s federal laws, which are designed to protect voters and voting rights, in past times individual states determined who could vote and, in a sense, determined who was a citizen. During the Early Republic, many states legislated voting rights and citizenship as the purview of white, property-owning men. By the 1830s, however, as the United States expanded its territory and witnessed the arrival of millions of immigrants and the creation of a new two-party system, most states enfranchised all white men.

Women and Black Americans were generally written out of state voting rights legislation, leading to a suffrage movement that galvanized many of the nation’s most aggressive activists, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, organizers of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, to clamor for women’s right to vote. These women’s struggles bore fruit with the ratification of the 19th Amendment, albeit decades after the founders of the movement had passed away.

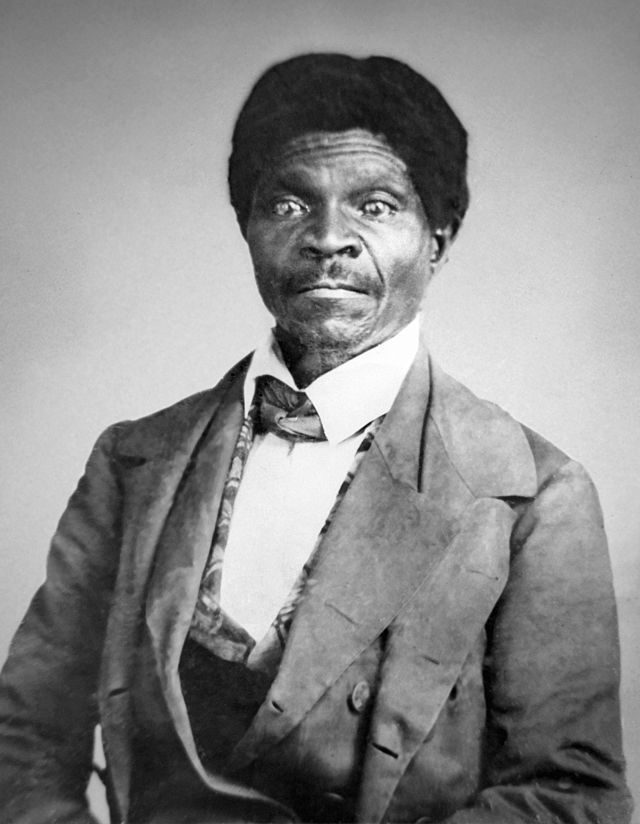

Black Americans, too, fought for the right to vote throughout the nineteenth century. Like their female counterparts, men like Robert Purvis and Frederick Douglass (right) delivered fiery speeches to agitate, and then attract, national attention. To Douglass, Black men deserved the right to vote as a matter of “simple justice.”

In 1857, the Dred Scott decision reinforced the notion of Black Americans as non-citizens, further hampering their right to vote. As the nation itself faced the consequences of slavery during the Civil War, Black men who fought and bled for the Union argued that their wartime service entitled them to vote. After the war, the rise of the Republican Party in the South and election of Black political leaders to local, state, and national office initiated the process of debating and drafting a new voting rights amendment. Five years after the war ended, Congress ratified the Fifteenth Amendment, which read, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Returning to “every vote matters” and the relationship between voting and citizenship, the Fifteenth Amendment not only (initially) prevented states from dictating who voted, it also naturally fulfilled the Thirteenth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery by bringing more Black Americans into the political community as citizens. The Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to Black Americans, and provided “equal protection under the laws” through due process, which acted as a shield for citizens whose lives after slavery were still quite precarious. The fulfillment of these two preceding amendments, the Fifteenth Amendment strengthened the political power of former slaves and Black men, making them active citizens via the right to vote and helped more Americans advance the founding principle of equality.

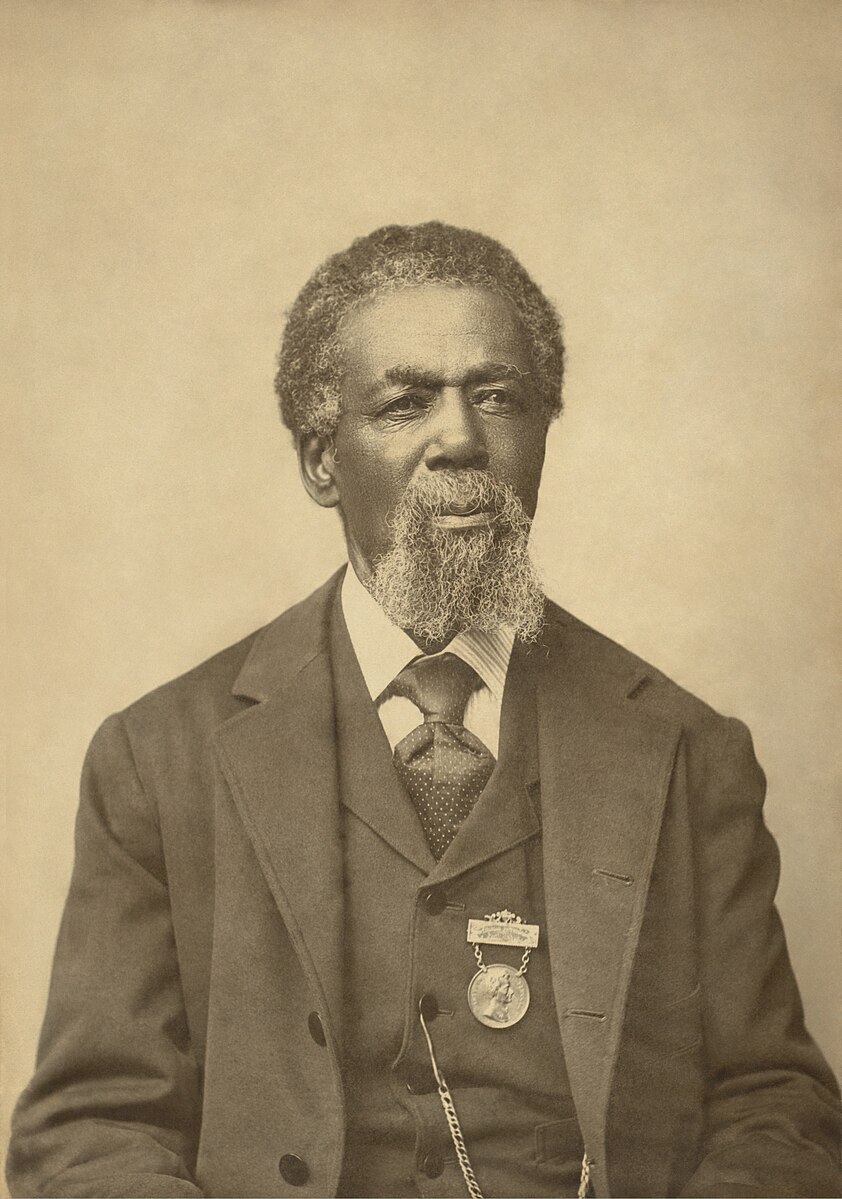

Making the Fifteenth Amendment a tangible reality required one thing: a Black man exercising his right to vote. This man was Thomas Mundy Peterson.

The son of a freedwoman, Peterson resided in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, once a major hub of the colonial slave trade. Thousands of enslaved Africans had come through Perth Amboy, and by 1800, the population of enslaved people in the state exceeded 12,000. While New Jersey did pass gradual emancipation laws in 1804, the state contained 2/3 of all enslaved people living in the North in the 1830s and would not formally abolish slavery until 1846. At the same time, given the number of Black Americans in Perth Amboy, many of whom lived in fear of slavecatchers and kidnappers, it was fitting that the city was also home to a community of radical abolitionists and featured a number of Underground Railroad stations. By the post-Civil War years, Perth Amboy’s population encapsulated the tragic and brutal legacy of slavery with the resilience of Black and white Americans willing to risk everything to ensure freedom.

Within 24 hours of Secretary of State Hamilton Fish certifying the Fifteenth Amendment, Peterson exercised his freedom and citizenship by becoming the first Black American to vote in a United States election under the protection of the federal government. The election itself was a referendum to either revise or jettison Perth Amboy’s town charter. Peterson explained, “As I advanced to the polls one man offered me a ticket bearing the words ‘revised charter’ and another one marked, ‘no charter.’ I thought I would not vote to give up our charter after holding it so long: so I chose a revised charter ballot.” Ballot in hand, he went to Perth Amboy’s City Hall and cast his vote to amend rather than eliminate the town’s charter.

Two crucial points can be made about Peterson’s historic vote. First, as the historian Gordon Bond pointed out,

This was the first time that anyone had cast a ballot that was both guaranteed and protected by the U.S. Constitution…Thomas Peterson consummated our modern understanding of the relationship between citizenship and suffrage in the fullest possible sense at that time.

While it would take decades for American women to receive the right to vote, Peterson’s vote and the votes of other Black men showed how the Constitution could protect citizens from being denied their voting rights. This active and protective function of the Fifteenth Amendment gave weight to the words of President Ulysses S. Grant, who after the amendment’s ratification delivered a special message to Congress in which he called it, “a measure of grander importance than any other one act of the kind from the foundation of our free Government to the present day.”

Second, though Peterson’s vote to amend and not eliminate the town charter seems mundane, it in fact emphasized how the strength of the Constitution lies in its flexibility. As Americans worked towards their cherished founding ideals, they exhausted much blood and treasure to bring about constitutional change in the form of amendments: The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution arguably represented the most radical changes in American history. While not as seemingly radical as those amendments, Peterson’s choice to amend the town charter reflects something many Americans take for granted: the people themselves can change the Constitution to better realize our founding principles.

Though important, Thomas Mundy Peterson’s vote does not overshadow the terrible rollback of voting rights that permeated the nation after Reconstruction ended in 1877. The rise of white supremacists in the South, the terror of the KKK, and arbitrary voting requirements prevented many Black Americans from participating in the nation’s body politic. Constitutional protections that failed in the short term ended up succeeding in the long term, however, as more Americans began working together to reinstitute the true meaning of citizenship and voting. At times this noble endeavor to secure the vote for Black Americans and women was marked by notable setbacks. That said, the Fifteenth Amendment’s ratification and immediate realization by Peterson solidified the right to vote as an attainable ideal of citizenship, making “every vote matters” a notion worth preserving and celebrating each election cycle.