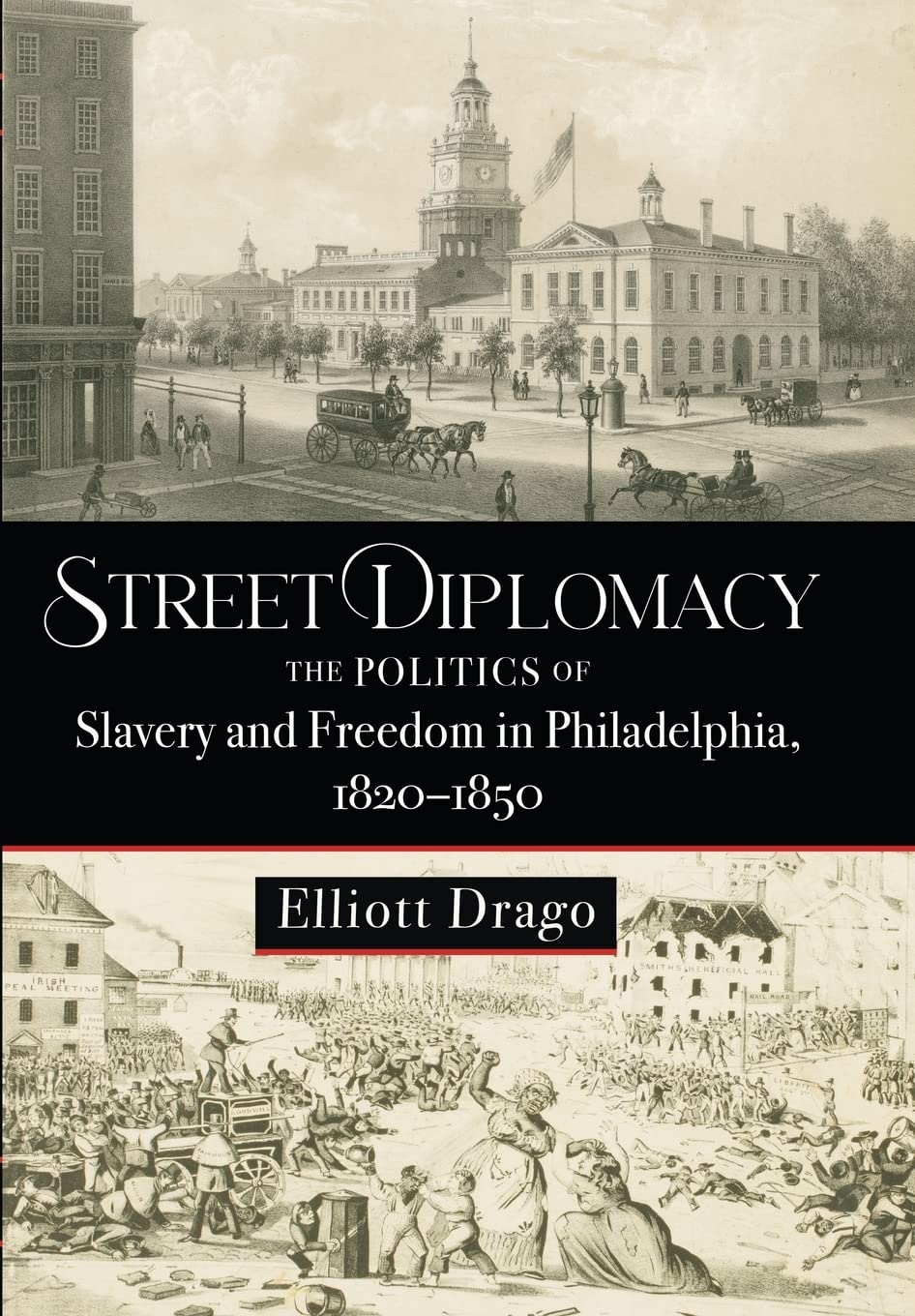

Street diplomacy in the nineteenth century

In the heart of Philadelphia, a runaway mother desperately held her infant son close as she matched wits with a ruthless slave catcher.

Bringing about a ‘more perfect union’

The mother, Catherine Thompson, escaped slavery in Maryland, married a free man named William Thompson, and eventually settled in Burlington County, New Jersey. There she gave birth to her son, Joel, and in August 1850, received an invitation from a Black man named James Frisby Price to visit him and his wife in Philadelphia. Catherine obliged, and she brought her infant son Joel with her to meet the Prices. But when she arrived at the Price household in Philadelphia, she found herself face-to-face with the notorious slave catcher, George Alberti, Jr.

Black Americans like Catherine Thompson faced a precarious freedom living in the antebellum North. Despite its history of abolitionism, including passing the nation’s first gradual emancipation act, the forces of slavery still lurked across the state of Pennsylvania, especially in the city of Philadelphia.

Labeled as “the most northern of southern cities” by one historian, Philadelphia hosted street battles over slavery throughout the period, which is the focus of my new book, “Street Diplomacy.” These battles took many forms, from fugitive slave rescues and the kidnapping of free blacks to vicious riots that led to the wanton destruction of black Philadelphia. These conflicts at the street level in Philadelphia became inextricably fused to state and national politics, as white politicians’ ability to classify enslaved African Americans both as property and as human beings represented a fundamental tension throughout the United States.

The source of this problem stemmed from the 1793 federal Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed slaveholders and slave catchers to pursue fugitives from slavery across state lines. Compounding this issue, states like Pennsylvania passed legislation that not only promoted freedom, i.e., their 1780 gradual emancipation act, but also sought to protect free black Pennsylvanians against kidnappers masquerading as “legal” slaveholders.

Ordinary black and white abolitionists practiced what I call “street diplomacy”: the up-close contests over freedom and slavery at the local level in Philadelphia that influenced politics and politicians at the state and national levels.

Throughout my book, I analyze the specific cases of kidnappings and fugitive slave retrievals that led street diplomats to pressure Pennsylvania lawmakers to pass “liberty laws,” i.e., state’s rights legislation designed to protect black Pennsylvanians. While most of these cases began on the streets of Philadelphia, all of them involved high-profile politicians, from governors to members of Congress to Supreme Court Justices. These struggles in Pennsylvania brought to light the illusory nature of borders between free and slave states, as well as the inherent tension over freedom and slavery that eventually led to the Civil War.

Returning to Catherine Thompson’s case, here we witness how she acted as a street diplomat in a high stakes game of life and death. She clung to her child for two reasons, the first being the most obvious: she loved him. Yet she also knew that if she refused to leave him in Philadelphia, Alberti would be charged as a kidnapper under Pennsylvania law if he brought them both back to Maryland. Even after enduring a savage beating from Alberti, Thompson would not let go of her child. Tragically, Alberti eschewed the legal ramifications, and shunning basic human decency, brought them back to Maryland, where Thompson’s former enslaver sold them further south, never to be heard from again.

However, black and white street diplomats convinced Philadelphia officials to press charges against Alberti and Price. The jury found them guilty and sentenced them to prison at the infamous Eastern State Penitentiary. In a cruel twist of fate, the newly elected Democratic Governor William Bigler of Pennsylvania pardoned the pair the next year, and both men returned to ply their grim trade on the streets of Philadelphia.

The case of Catherine Thompson and her infant son Joel was one in a plethora of similar events that exploded across the north prior to the Civil War. Confronted by such cases, white Americans soon began to chafe over the inhumanity of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which charged all Americans with aiding in the return of runaways. In time, Americans increasingly rejected being beholden to slaveholders who hoped to spread slavery, and not freedom, across the nation. Northerners elected a president in 1860 who refused to accept the expansion of slavery as the true mission of the U.S. The Civil War reflected the culmination of street diplomacy, the efforts of black and white Americans who worked together to destroy slavery and bring about a more perfect Union.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).