U.S. Constitution teaches us all how to lose

Jerry Weinberger | Michigan | 12:30 pm September 17, 2014

We Yanks love national “days.”

There is one for mothers and fathers and Leif Ericson and even catfish.

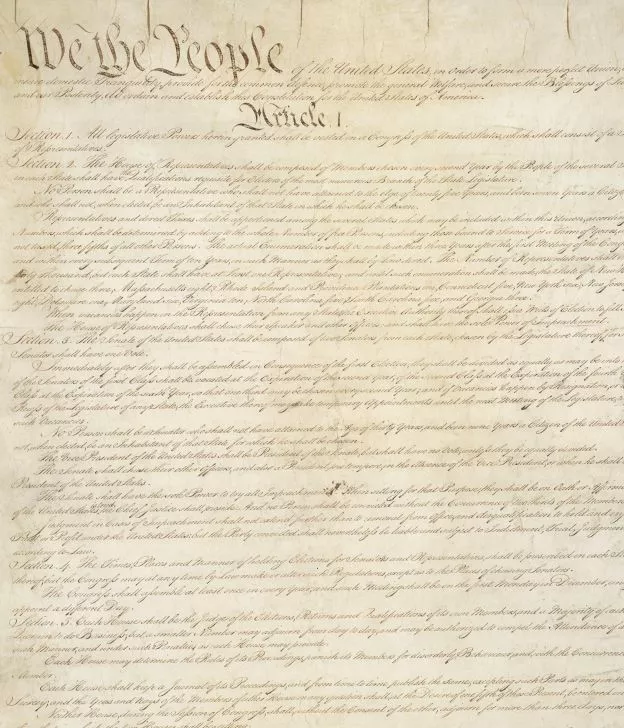

In 2004, the U.S. Congress required that all colleges and universities getting federal funds do something to mark the signing of the U.S. Constitution. So, September 17 is “Constitution Day.”

It’s surprising this took so long and involved goading our institutions of higher education. Some on campus care about the constitution: Hats off to non-profit organizations like The Jack Miller Center for its ongoing support of constitutional studies in general as well as Constitution Day programs in particular. But even more should care, because our Constitution really is a big deal.

When the President takes the oath of office spelled out in Article II, section 1, he swears to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

On becoming a new citizen, immigrants declare “on oath” that they will “support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America.” The same is true for members of Congress, cabinet secretaries, and military officers.

On these most solemn national occasions there is no mention of allegiance to our American cultural heritage or history, no mention of Puritans or purple mountains or amber waves of grain or the flag. That’s because the United States was the first polity in history founded explicitly on a set of abstract and universal political ideas: equal individual rights and republican and limited government. Only the constitution, a short and boring and mechanical document that turns these ideas into practice, makes us who we are as a political community.

When the Constitution was signed, popular self-government was not in great repute around the world. Democracy was thought to be unstable and especially prone to corrosive ambition, civil strife and tyranny.

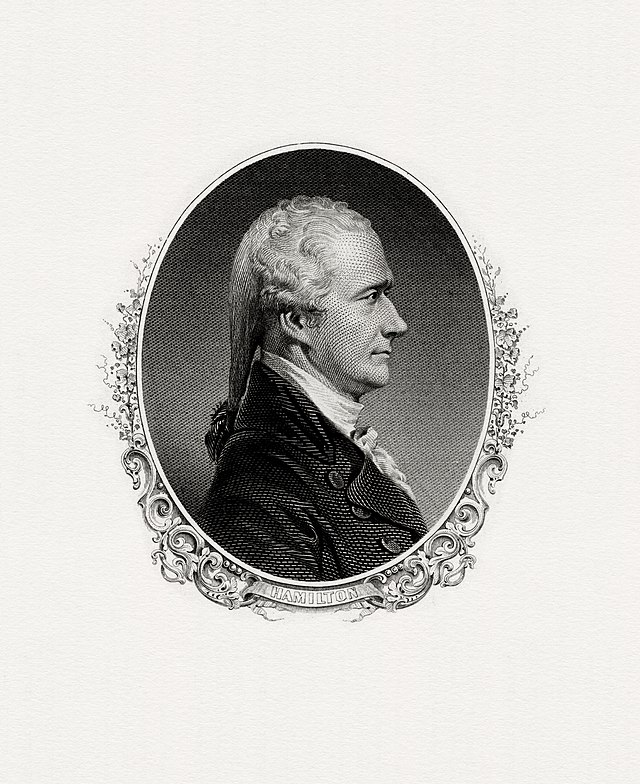

In The Federalist, Alexander Hamilton argued that it was up to his country to prove that people could govern themselves “from reflection and choice” rather than “from accident and force.” The great achievement of the constitutional founders was to understand that for the American people to effect this proof they had to impose limits on their own, exclusive power to govern.

To the pride of independence, the people had to add a dose of skepticism about their own goodness. Thus James Madison reminded fellow citizens: “But what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

Hence federalism and the separation of powers; and as regards the latter, “the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department consists in giving to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist the encroachments of the others.” Ambition must be set against ambition, he said, and “the interest of the man must be connected to the constitutional rights of the place.”

The constitution, in other words, is designed to produce a limited form of what we now deride as “gridlock.” Even when our government gets things done, everybody loses to some degree.

The constitutional machine teaches us all how to lose. That’s how it makes us who we are as citizens. An experienced Iraqi politician I know once told me that his people could not become truly democratic until they learn how to lose. He was right: Read our Constitution.

Jerry Weinberger is University Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Michigan State University. He is Director of the LeFrak Forum and Co-Director of the Symposium on Science, Reason, and Modern Democracy, both at Michigan State, and is an Adjunct Fellow of the Hudson Institute in Washington, D.C.