The Education of a Statesman

JMC President Hans Zeiger’s writes for the 62nd issue of National Affairs in winter 2025.

Americans are clearly troubled by the state of their political leadership and the quality of candidate choices in recent elections. According to a Pew Research Center study released in September 2023, 72% of Americans rate the overall quality of political candidates in recent years as poor, while just 26% regard them favorably. These findings are roughly the same across the political spectrum and represent a marked decline from 2018, when 47% of Americans gave positive marks to the candidates running for office.

The Pew report also showed that only 22% of respondents believe most candidates run for office to address issues that voters care about, while just 15% believe service to the public is a leading motivator for political aspirants. Additionally, the survey asked an open-ended question that called on Americans to describe the current state of politics in a word or phrase. The top terms chosen were “divisive,” “corrupt,” and “messy.”

The 2024 presidential election raised further questions about the quality of the nation’s political leadership. In a September 2024 Gallup poll, fewer than 50% of adults gave favorable ratings to either Donald Trump or Kamala Harris. With that election now behind us, we would do well to consider why Americans have lost trust in their political leaders, and how we might restore that trust.

The time is right for an honest assessment of the civic-leadership training, both formal and informal, that prepares Americans for office. What kind of preparation should we expect of the men and women who are suited to hold positions of public trust in our republic? What are the cultural and institutional impediments to forming capable leaders who run for office? And what can we do to overcome those impediments?

The systems that prepare citizens to hold elected office in America today are wide-ranging — from formal schools to vocations, institutions of civil society to political institutions themselves. Some are more functional than others. By surveying the history and current state of these systems, we can come to a better understanding of the political-leadership formation that has sustained the American experiment for nearly 250 years and how we might renew it in our own generation.

Guardian of the guardians

Throughout the history of political societies, leaders and intellectuals have sought to identify the virtues, knowledge, and skills needed to govern well, and to develop institutions capable of educating the next generation of leaders with this wisdom in mind. Plato’s Republic, one of the founding texts of Western civilization, articulates some of the fundamental questions involved. As Socrates asked when inquiring about the guardians of the city-in-speech he was building: “But how, exactly, will they be reared and educated by us?”

Political philosopher Allan Bloom elaborated on the dilemma Socrates raised in a preface to his translation of The Republic: “In a sense the problem of the Republic was to educate a ruling class which is such as to possess the characteristics of both the citizen, who cares for his country and has the spirit to fight for it, and the philosopher, who is gentle and cosmopolitan.” Plato’s theoretical regime itself depended on the success of this education: As Bloom wrote, there are “no guardians above the guardians; the only guardian of the guardians is a proper education.”

Cicero’s extensive reflections on leadership preparation, written three centuries after The Republic, were borne of much personal experience. Wise citizens, he believed, should be prepared to rule if needed, and therefore they have a duty to learn the “science of politics.” The ideal study of that subject, according to Cicero, consisted of “the union of experience in the management of great affairs” with formal studies in the liberal arts.

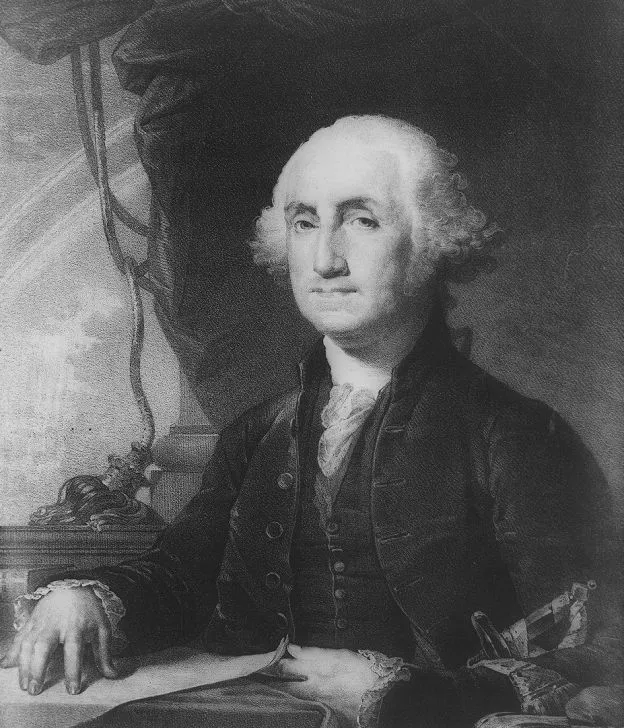

The American founders who composed the essays of The Federalist — Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay — were thoroughly Ciceronian in this sense: They were men of public affairs as well as avid readers and students of the great philosophers and historians throughout the ages. The Federalist itself constituted a kind of public education for the generation that would ratify the Constitution, conveying the lesson that a functioning constitutional order depends on the elevation and maintenance of wise and virtuous leaders. Our first president seized on this theme, emphasizing the need to educate future citizen leaders of the republic he helped establish..

Education

In a letter to Hamilton in 1796, George Washington identified education as “one of the surest means of enlightening [and giving] just ways of thinking to our Citizens.” Like Cicero before him, he advocated for leaders of the republic a liberal education — one “by which the arts, Sciences [and] Belles lettres, could be taught in their fullest extent,” as he wrote to the commissioners of the District of Columbia in 1795. And again, like Cicero, he insisted that a “primary object” of that education be “the education of our youth in the science of government.”

Washington knew that wisdom in statecraft was often learned the hard way — through experience. In draft notes for his first inaugural address, he wrote that American political leaders had “purchased wisdom by experience.” Indeed, political life itself is a powerful teacher of political prudence, as we will discuss later on.

But Washington also knew that intellectual capital cannot be assumed; it must be cultivated. He therefore took pains to identify the substance and sources of the education fit for citizen leaders of a republic.

Such education, he asserted, should instill in Americans six different principles:

[T]o know and to value their own rights; to discern and provide against invasions of them; to distinguish between oppression and the necessary exercise of lawful authority; between burthens proceeding from a disregard to their convenience, and those resulting from the inevitable exigencies of society; to discriminate the spirit of liberty from that of licentiousness, — cherishing the first, avoiding the last; and uniting a speedy but temperate [vigilance] against encroachments, with an inviolable respect to the laws.

The verbs in this list are worth dwelling on: “know,” “value,” “discern,” “distinguish,” and “respect,” as well as “cherishing” and “avoiding.” They point to the habits of thought and learning that Washington believed should be nurtured in the nation’s citizenry.

To achieve his vision of civic education, Washington advocated establishing a national university. He believed that bringing together young Americans from all kinds of backgrounds, regions, and perspectives to learn and form civic friendships would help forge a national identity and shape the character of the new nation. In his letter to Hamilton, he wrote that a national university located in the nation’s capital would allow “those who were disposed to run a political course” to “be instructed in the theory [and] principles” of politics while being exposed to its practice. For, as he stated in a speech before Congress, those who would one day be “intrusted with the public administration” must be taught “that every valuable end of Government is best answered by the enlightened confidence of the people.” In other words, good public policy depends fundamentally, in every instance, on public trust.

Although Washington’s plan for a national university never came to fruition, the founders agreed on the need for formal and informal civic education for the nation’s future leaders. Given their experience of the Revolution and the founding, educational leaders were aware of the fragility of the American experiment and the need for a solid intellectual foundation for republican citizenship and statesmanship. As public schools took shape in the 19th century, they maintained a primary focus on the molding of good citizens.

This emphasis on citizen competence stood in growing tension with American education’s emphasis on economic competence. Over time, as educational theorist E. D. Hirsch, Jr., has pointed out, school administrators, policymakers, and others sought to develop a practical education for economic ends, whereby young people could attain the knowledge required to secure for themselves the American Dream. American education gradually shifted its emphasis away from civic education and toward promoting the success of individual students. In recent years, educational leaders and policymakers have routinely emphasized science, technology, engineering, and math over the humanities. Civics remains a part of the curriculum, of course, but it is no longer predominant.

This was also the case in America’s universities. For students today who wish to pursue a life devoted to civic matters — whether as elected officials, lawyers, journalists, scholars, government-agency staff, political advocates, or responsible citizens pursuing all types of private vocations — certain major fields of study at the post-secondary level, including political science, history, public policy, public administration, and more, would appear to be logical pathways of preparation. Yet these fields often provide minimal training for broad civic competencies.

Instead of providing an education in the intellectual foundations of leadership for a constitutional republic, these disciplines have turned their attention — and their professional rewards and incentives — toward ever-narrowing research agendas. Political science is dominated by quantitative studies of political behavior; history is largely directed toward topical research and social histories focusing on factors like race and gender. College students who set out to gain political wisdom for tackling the great challenges of their generation are likely to be disappointed.

If formal education has sometimes failed to live up to its civic purposes, there is some consolation to be found in the American tradition of self-education. Harry Truman did not have a college degree, but he did have a love of reading that began in his formative years. “Reading history, to me, was far more than a romantic adventure,” Truman would say. “It was solid instruction and wise teaching which I somehow felt that I wanted and needed.” Ronald Reagan favored books by the likes of Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Michael Oakeshott. Abraham Lincoln looked to older — though no less significant — examples, as Lord Charnwood recounted:

It astonished [Lincoln’s law partner William] Herndon that the serious books [Lincoln] read were few and that he seldom seemed to read the whole of them — though with the Bible, Shakespeare, and to a less extent Burns, he saturated his mind….Some time during these years he mastered the first six Books of Euclid. It would probably be no mere fancy if we were to trace certain definite effects of this discipline upon his mind and character.

Those few books Lincoln read, Charnwood explained, “were part of one study….[B]ut the study, in the broadest sense, of which these years were full, evidently contemplated a larger education of himself as a man than professional keenness, or any such interest as he had in law, will explain.”

The school of civic society

Traveling through America in the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville gave high marks to the state of civic literacy in America. Though some of this knowledge came by way of formal schooling, political education, as Tocqueville recognized, also came through the work of governing itself. “It is from participating in legislation that the American learns to know the laws,” he wrote, “from governing that he instructs himself in the forms of government.”

Nineteenth-century New Englanders were serious students of civic life, steeped in the local political order and determined to comprehend it. Tocqueville observed the political and civic enculturation among New Englanders in their local townships, writing that the

inhabitant of New England…habituates himself to the forms without which freedom proceeds only through revolutions, permeates himself with their spirit, gets a taste for order, understands the harmony of powers, and finally assembles clear and practical ideas on the nature of his duties as well as the extent of his rights.

This American penchant for civic localism continued into the 20th century. A 1930s Kiwanis Club publication described the group’s purpose as serving as a “clearinghouse on public affairs” for “thousands of fine Americans who are seeking for authoritative information on the perplexing problems and issues of the present.” In 1950, a Rotary Club leader named Walter Williams — speaking at the club’s convention that year as its post-war membership was burgeoning — linked service in the group to American values. “The democratic way is the Rotary way,” he declared. “America’s great dynamic strength exists because out of the grass roots each citizen has been a dynamic producer, planner, and doer.” A practical example, said Williams, was “Rotary community service.”

Institutions of civil society have long played a powerful role in civic formation. Professional organizations, chambers of commerce, labor unions, and parent-teacher associations are among the many kinds of groups that train their members in legislative advocacy, political campaigns, public-meeting facilitation, board governance, and other ways of public life. A parent who gets involved in a push for neighborhood traffic safety, a veteran who organizes a Memorial Day ceremony, a small-business owner who forms a Main Street coalition of local shops — all of these individuals may soon find themselves seeking (or being sought out) to run for office.

While these outlets for civic involvement and leadership remain important features of society today, people tend to hone their civic skills in different ways than they did during the mid-20th century. “Today it is not enough to learn the transferable skills that may be common in traditional membership organizations such as service clubs and churches,” wrote sociologist Robert Wuthnow in 1998. “Increasingly, good citizenship is also defined in terms of innovative skills that include networking, dealing with diversity, initiating new projects, and filling niches in an already crowded institutional environment.”

Today, someone interested in running for a local or state office, or otherwise making a positive impact at those levels, would still benefit from joining a local service club, volunteering for a special-interest group with influence in the community, or serving on a non-profit board. Despite their changing form, these civil-society organizations remain a powerful force for civic enculturation throughout the country.

Vocational training

In our democracy, political leaders come from all kinds of vocational backgrounds. Military service imbues people with a sense of duty, teamwork, and professionalism. Business ownership provides practical training in negotiation, strategy, and communication. For many who enter politics, legal work serves as a useful gateway. “The profession I chose was politics; the profession I entered was the law,” Woodrow Wilson once said. “I entered one because I thought it would lead to the other.”

As they proceed through their careers, professionals of various stripes may discover within themselves leadership dispositions, develop governance skills, or identify pressing social problems. A non-commissioned military officer may develop a love for serving his troops; a social-service worker may determine that structural changes are desperately needed to alleviate poverty; a retired corporate executive may seek a new way to make the best of his talents for team building and problem solving. Vocational experience and observation have at least as much bearing on the ideas and practices of leaders as anything they read or learn in formal coursework.

President Reagan offers a powerful example of how a career can prepare citizens for political leadership. In her biography of Reagan, Peggy Noonan described how the man who came to be known as the “Great Communicator” learned about public communications. “He had learned how to talk to a camera when he did TV,” she wrote. “So [as president,] he went over the heads of the press…and went on television and radio and told everyone what he was doing and how things were going.”

As in Reagan’s case, the professional skills one hones can translate directly to politics. In other cases, a person’s vocation can expose him to the people he will one day lead. As a frontier lawyer going about his work without much renown, Lincoln was “all the while in secret forging his own mind into an instrument for some vaguely foreshadowed end,” noted Charnwood. In what is surely among the best summaries of Lincoln’s education for leadership, Charnwood wrote:

He was not merely amusing himself and other people, when he chatted and exchanged anecdotes far into the night; there was an element, not ungenial, of purposeful study in it all. He was building up his knowledge of ordinary human nature, his insight into popular feeling.

This kind of education could not have been obtained at the most elite university — nor would Lincoln have been in a position to pursue it there.

Indeed, elite credentials are of less utility in politics than in other vocations. Stimson Bullitt made this point in his 1959 book To Be a Politician: “Graduates of obscure professional schools,” he wrote, “have been more likely to enter politics than those from the leading schools because in politics their undistinguished formal training is not held against them.” A recent Manhattan Institute report by Andy Smarick confirms the point. Surveying the educational backgrounds of today’s public officeholders, Smarick found that most of them attended not Ivy League or other private universities, but public and in-state colleges and graduate schools.

For all the dysfunctions evident in American politics, certain service vocations still do an exemplary job of preparing citizens for elected office. Emily Cherniack noted as much in a recent symposium for the journal Democracy, pointing to community-service programs, the military, and other “public-facing, mission-driven organizations” as providing the groundwork to build servant leaders. These service positions “equip individuals with a deeper understanding of sacrifice, teamwork, and how to work toward the common good,” shaping “resilient leaders who are adept at empathizing with constituents, communicating effectively and honestly, and addressing societal issues with integrity.”

A lifelong pursuit

Beyond formal and informal education, participation in civil society, and vocational experience, on-the-job training is also vital for citizens seeking public-leadership roles. This requires intentionality and focus among officeholders.

Cicero recognized the value of statesmen’s “improving and examining” themselves while in office, not only for their own efficacy, but also to set an example for their fellow citizens. Political scientist Aaron Wildavsky made a similar point, writing that leaders “must be continual participants in their own education.” This requires certain disciplines of learning and reflection, from both continued study and experiences in politics.

Political practitioners have much to learn from the works of scholars who devoted their lives to the study of policy, history, philosophy, and related subjects. John Locke bemoaned the limitations of politicians and political philosophers who failed to spend time in one another’s waters and who would “not venture out into the great ocean of knowledge” beyond “their own little spot.” Yet occasionally there are political officeholders who seek to unite action and contemplation. In The Forum and the Tower, legal scholar Mary Ann Glendon pointed to Oliver Wendell Holmes and Eleanor Roosevelt as two examples. Several U.S. senators — Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York foremost among them — did what they could to bridge the world of ideas and the world of policy.

Of course, political leadership itself is the source of endless wisdom and lessons to be applied, both in one’s own service and in mentorship to others. Hubert Humphrey — a mayor of Minneapolis, senator from Minnesota, and vice president — indicated as much by titling his autobiography The Education of a Public Man. Another senator, Richard Neuberger of Oregon, wrote an essay for American Magazine titled “Mistakes of a Freshman Senator” in June 1956 — a year and a half after he started his service in the upper house of Congress. Even as a distinguished political journalist and former Oregon state legislator, Neuberger admitted that he had a lot to learn about how to be an effective senator.

Everyone in political life must learn, especially from their mistakes. Senator Alben Barkley of Kentucky, who also served as vice president in the Truman administration, made this point to Neuberger. “If you meet a man here in this chamber who advises you he never has made a mistake as a senator,” he observed, “you have met an Ananias — a liar. There are only two things to do about mistakes — learn from them and don’t let them spoil your sleep.”

Lessons learned at one level of service often assist those who seek higher offices. Political scientist Joseph Schlesinger described local and state positions, or what he called “base offices,” as “good places to look for the apprenticeship or sifting of political leaders.” All four presidents whose likenesses appear on Mount Rushmore got their start in politics as state legislators. As Neuberger wrote:

[I]f any place should be hospitable to young Americans just starting in their political careers, it is a state legislature. This tradition is rooted securely in the history of the United States. It once was as normal for future statesmen to begin in their home legislatures as it is now for the next generation of major-league baseball players to commence on the neighborhood sand lot.

This tradition was renewed in the early 1970s with a wave of young local and state legislators coming of age after the 26th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, which allowed 18-year-olds to vote. It was during this era that President Joe Biden got his start as a council member on a county legislative body in Delaware. A generation later, Barack Obama began his political career in the state senate of Illinois.

Forming citizen leaders

Notwithstanding the dismal findings of the 2023 Pew survey on political leadership, not all is lost: Americans rate local and state politicians far better than federal officeholders. As Daniel Stid observed in the Democracy symposium:

All across the country, in statehouses, county commissions, city councils, and mayors’ offices, thousands of dedicated and pragmatic politicians are leading in a responsible way, exercising the powers of the offices to which they have been elected to solve problems in the public interest — what I call leading to govern. There are more of these public-spirited leaders than we know, and we are in their debt. Yet for representative democracy to flourish, we will need even more of them in the years ahead.

Even with excellent yet often unheralded citizen leaders providing abundant reason for hope, we must find ways to widen the talent pipeline for informed and ethical public service.

To truly renew a leadership ecosystem for the American republic in the 21st century, every institution and community must do its part. Preparation for citizenship can be thought of as a “layer cake,” as Jeff Sikkenga and David Davenport put it in A Republic, If We Can Teach It. Historical events and lessons learned in early years can become the basis for more in-depth conversations as citizens age, helping them feel part of a common story. Civic learning doesn’t end in school, but continues throughout the lifespan of a citizen. The influences are wide ranging: One never knows how a history book, political speech, or church sermon in one generation will shape the character of leaders in a later generation.

Institutions of higher education bear a particularly important responsibility in this regard. Nowadays, political scientists tend to focus far more on policymaking, elections, voter attitudes, and other measurable subjects than they do on the complex influences that inform political behavior. Wildavsky recognized this imbalance in his discipline in 1984, writing that “[s]ocial scientists study deciding rather than learning because social scientists assume that leaders already know what to do.” Political scientists would do a valuable service to the country by giving political preparation the scholarly attention it deserves.

More important than any scholarly research agenda, however, is the actual teaching of statesmanship, as understood by Cicero, Washington, the authors of The Federalist, and many other great leaders throughout history. While formal education is not everything — the examples of Lincoln and Truman, among others, make that abundantly clear — its exercise has been badly neglected at every level of American education for decades. If we wonder why Americans give such poor ratings to political leaders and the candidate selection pool, we need only look at our societal failure to teach political leadership as an explanation. In the absence of education for civic and political leadership, the performative politics all too familiar in America today becomes a self-perpetuating model of public behavior, both by setting a poor example for those who aspire to political life and by turning away many good citizens who would otherwise pursue public service.

Some recent developments within higher education offer hope on this front. Stanford and Johns Hopkins University are among a growing number of private universities instituting new programs for civic education. In fact, at least 13 schools and centers have now been formed at public universities in eight states with the goal of renewing the teaching and study of civic thought and leadership. As these programs grow, they promise to attract thousands of politically inclined students seeking an education in leadership. They provide a model for other universities to emulate.

Beyond educational institutions, the watershed moment when a citizen is first elected to office represents a key opportunity for an education in governance. Yet according to Craig Volden of the University of Virginia and Alan Wiseman of Vanderbilt University, candidates “often receive much more training on how to run and win their campaigns than on how to govern upon achieving electoral victory.” Layla Zaidane of Future Caucus wrote of the need “for more mentorship and professional development programs for newly elected lawmakers.” She pointed to recommendations from the U.S. House Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress as offering practical steps toward improving the onboarding of new members of Congress.

Meanwhile, civil-society organizations are helping to create an ecosystem for the development of responsible leaders for 21st-century America. These include Zaidane’s Future Caucus, set up to provide leadership development and encourage bipartisan collaboration among Millennial and Gen-Z state lawmakers; the New Politics Leadership Academy, founded and led by Emily Cherniack to train cohorts of political and civic leaders; and the Leadership Alliance for a More Perfect Union at the Joseph Rainey Center for Public Policy, established to develop elected officials’ leadership skills. Other examples include the National Conference of State Legislatures and the Council of State Governments, which provide a variety of trainings and other resources to public officials; the Carl Levin Center for Oversight and Democracy at Wayne State University Law School, which assists legislative bodies in fulfilling their oversight functions; and the Center for Effective Lawmaking, which promotes legislative competence through an array of research and public information.

Public and non-profit organizations are also doing their part to encourage leaders to engage with the world of ideas. The Library of Congress hosts dinners for members of Congress to learn from various scholars. The Rodel Institute, led for years by former congressman Mickey Edwards, gathers select cohorts of local and state elected leaders to join in readings and conversations with alumni such as Vice President Harris, Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, and former Arizona governor Doug Ducey. And the American Conservatism and Governance Fellowship, led by Andy Smarick at the Manhattan Institute, exposes public officials to readings from the American political tradition. With programs like these, there is hope for a renewal of republican statesmanship in our time.

Citizen leadership is an adventure, and it can be a source of joy — one that anyone who appreciates the privilege of life in a free society would do well to consider. But for such leadership to proliferate, educational, civic, vocational, and political institutions must share a commitment to its widespread formation and maintenance. Scholars, teachers, higher-education administrators, journalists, philanthropists, and political leaders themselves must all do their part, as we near America’s 250th birthday, to renew the teaching of political leadership. It could well be the most important cause of our generation.

Hans Zeiger is president of the Jack Miller Center. He previously served as a state legislator in Washington.