The Centrality of the Constitution in the Civic Education of Americans

In honor of the anniversary of the signing of the US Constitution on September 17, 1787, Constitution Day is marked with a lecture by Wilfred M. McClay. McClay’s lecture was the 10th in a series named for distinguished AEI scholar Walter Berns. By Wilfred McClay. American Enterprise Institute. November 30, 2021.

Queen Elizabeth II is now the longest-reigning monarch in British history, having easily surpassed the formidable 63-year rule of Queen Victoria and continuing to add to her record numbers at the time of this writing, in the summer of 2021. Her achievement has been widely celebrated in the American news media, partly because we Americans seem to feel a great fondness for Elizabeth and an enduring fascination with the British royal family.

Just why is that? This seems like rather strange behavior for a country that came into being through a revolution against one of Elizabeth’s predecessors. Not to mention being a country whose Constitution—the 234th anniversary of which we celebrate in 2021—incorporated the principle that “no title of nobility” would be granted by the United States and that every state in the Union was to have a “republican” form of government—meaning: No kings and queens allowed.

There are probably more elements to that puzzle than there is space in these remarks. But surely part of the answer lies in the durable bonds that still link our two nations, in the form of shared language, customs, laws, and culture. Our country may have been born in rebellion, but our Constitution’s form and contents are deeply indebted to the British precedents and influences that shaped it, especially following the long and often bloody struggles for power during the 17th century culminating in the constitutional arrangements established in the Glorious Revolution. More generally, the “special relationship” between our two nations has proved deep and enduring, despite our occasional differences. There can be no doubt about it; we Americans have a rooting interest in the Queen’s well-being.

But something else is at work too. The Queen’s most important role in her own country is an impersonal one, her office as a disinterested and trans-partisan symbol of the United Kingdom (and the Commonwealth). Elizabeth performs that role with superlative grace and is arguably the single most compelling symbol of political stability and unity in today’s world. Despite all the changes and fissures that have afflicted British society since her reign began in 1952, including a radical transformation of the nation’s international status and its demographic makeup, not to mention the endless foibles of the royal family, her matronly but commanding presence reassures her people—and those of us who care about them—that the essential things will carry on, year in and year out. Whether that essential British core will survive the British nation’s eventual loss of this extraordinary woman is anyone’s guess, but the odds are high that the monarchy she sought to preserve will endure so long as a reasonably coherent British nation also endures.

There is something enviable in that. We Americans often feel the absence of such unifying personal symbols in our own contentious nation, and many of us yearn for them—especially at the present moment, when so much in our national life seems to be fiercely contested and when the presidency itself, no matter who occupies that office, seems more often to be an avenue of division rather than a symbol of abiding unity. Seeming to lack the symbols of unity, we fear that we may be losing the thing itself. It is not an unjustified fear.

But in fact we do not lack for unifying symbols, if we are willing to avail ourselves of them. Ever since George Washington gallantly refused the office of monarch, we have been on a different path—a path on which our commitment to impersonal laws and impartial procedures overrides our commitment to any one man or woman as our symbolic head.

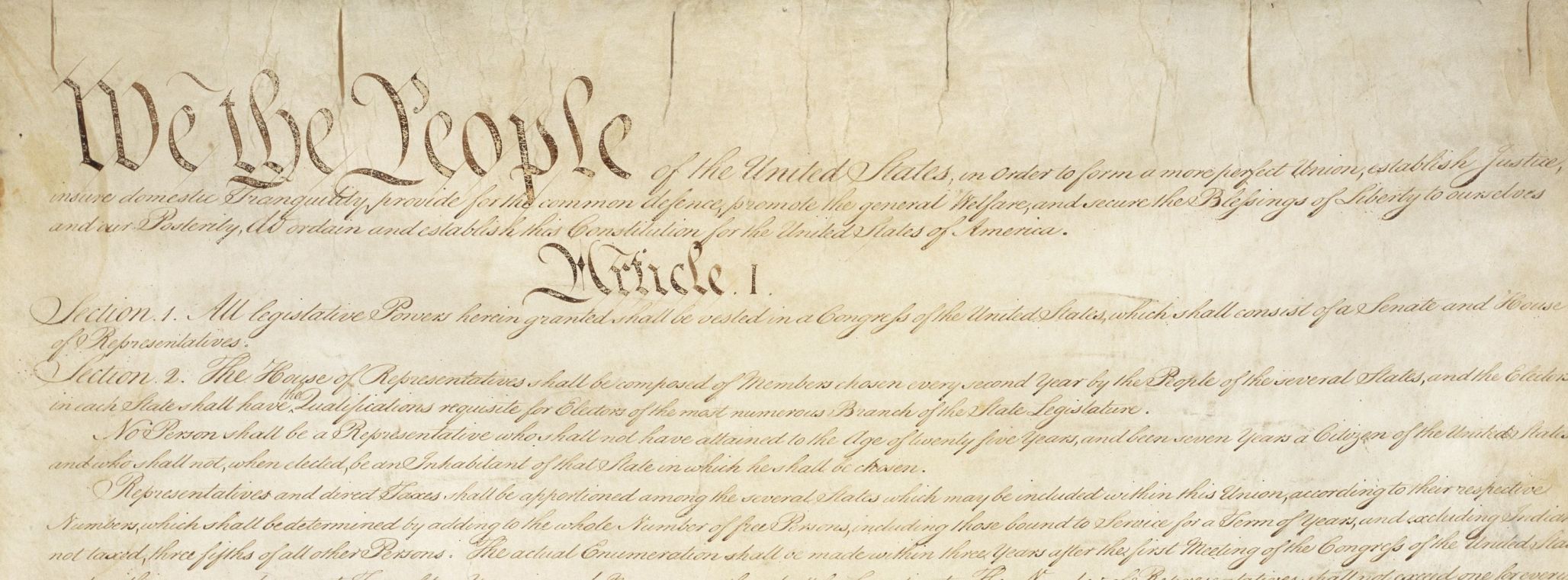

For us it is a document, our Constitution, that plays the role of democratic monarch and thereby serves as the chief and most durable symbol of our national unity and our commitment to one another as one nation.

That is not all the Constitution does, of course. It is first and foremost a legal document, a written expression of the supreme law of the land, establishing the fundamental structure of the national government, broadly delineating its relationship to the state governments, and explicitly protecting certain individual and collective rights against the power of the national government. As such, it is not in any obvious way an equivalent to a monarch. And like most legal documents, it also is a rather dry affair. Unlike the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution contains, apart from its Preamble, almost no stirring language proclaiming the sweeping idealism of its claims.

But its symbolic function is nevertheless an absolutely crucial part of what it has been for us. We have lived under its authority for the entire span of our nation’s history, apart from a brief prelude under the Articles of Confederation.1 Hence, our national identity is difficult to conceive apart from it. To do so would mean entry into utterly uncharted waters. By contrast, the French have over the centuries cycled through a multitude of regimes—monarchies, republics, and empires—and yet French identity has never been reliant for its existence on any particular form of government. We think of the United States as a young country, and perhaps we are right to do so. But the established life of the American nation has not existed apart from its Constitution, which happens also to be the world’s oldest constitution. Hence it is especially proper at a time of such intense contention in our national life that we pause to remember and reflect on the meaning of that fact.

Notes

- The question of exactly when the Constitution became the law of the land is surprisingly complex. An excellent and fairly dispositive treatment of the matter is found in Gary Lawson and Guy Seidman, “When Did the Constitution Become Law?,” Notre Dame Law Review 77, no. 1 (2001), https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol77/iss1/1/.

Wilfred M. McClay is Professor of History at Hillsdale College.