Embracing Civics Can Help Restore Trust in Higher Education

Civics is an antidote to the cynicism that reduces everything to power and to the nihilism that seeks only to subvert and tear down.

At the dawn of a new year, administrators, professors and students of elite universities stand raw and exposed before an increasingly dubious public. While university leaders appear weak and aimless and students ideologically adrift, it would be a mistake to give up on our universities. They are too important to freedom in America.

For these institutions, part of the way forward now must be a return to civics and civic education to prepare the next generation to steward the American experiment. Since the founding, Americans who have thought deeply about how to “secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity,” to quote the preamble to the Constitution, have emphasized the critical importance of higher education.

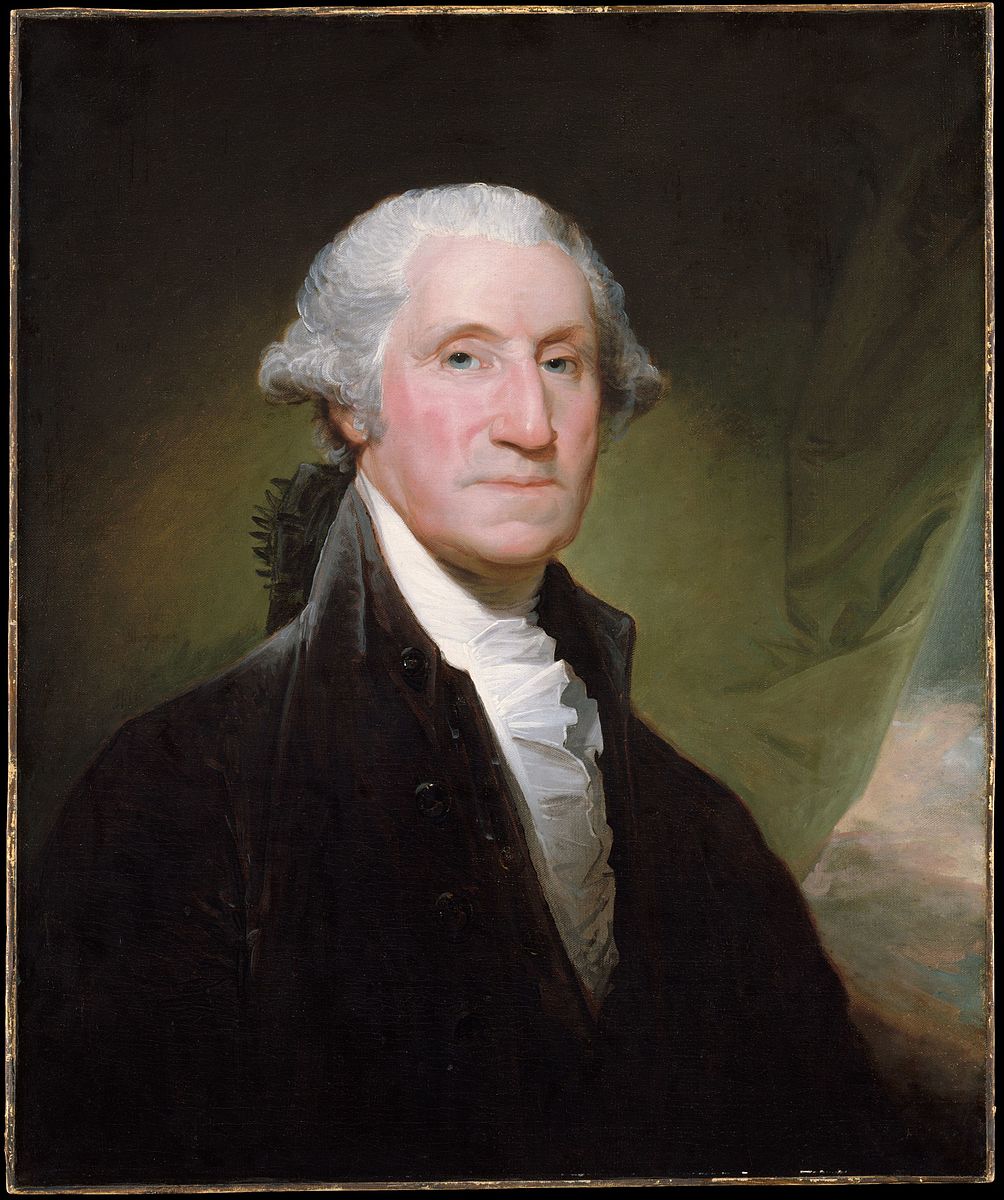

In his Farewell Address, George Washington explained that American government is “the offspring of our own choice,” and the preservation of freedom depends on citizens who perform the “duties enjoined by the fundamental maxims of true liberty.” These “duties,” he said, include respect for the Constitution and laws that safeguard our liberty. In his last public appearance as president, Washington proposed to Congress the creation of a national university for the purpose of preparing a corps of civic leaders who would ensure that future generations know how to perform the duties necessary to preserve freedom in America.

Others carried Washington’s ideas forward by creating new state universities. Typical were the first commissioners of the University of Virginia, including Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who envisioned higher branches of education that would “form the statesmen, legislators and judges, on which public prosperity and individual happiness are so much to depend.”

In recent years, flagship public universities across the country have recovered this founding vision by launching new schools and institutes to prepare leaders who know and appreciate the principles of a free and prosperous society. These efforts, buoyed by support from concerned alumni and engaged governing boards, are underway in Arizona, Texas, North Carolina, Tennessee, Florida, Utah, and Ohio. More will surely follow. Common to each is a renewed focus on the serious study of American civics.

Although civic education is an ancient concept, the idea of civics as a field of study is a 19th century American invention. Civics — the study of the rights and duties of citizenship — is a word that comes from a group of citizens who contemplated the kind of education needed to sustain the rebirth of freedom after the carnage of the Civil War.

Henry Randall Waite, a clergyman, editor, and journalist, was the first to use the term in 1885 when he founded the American Institute of Civics, an organization dedicated to the “special attention to Civics in higher institutions of learning” in order “to secure wise, impartial, and patriotic action on the part of those who shall occupy positions of trust and responsibility, as executive and legislative officers, and as leaders of public opinion.”

American civics draws on multiple academic disciplines, including politics, economics, philosophy, history, and law, but it is not reducible to any one of them. It is anchored in the study of Western civilization and American constitutionalism, and it fosters a patriotism that is spirited, thoughtful, and open to critical self-reflection.

Civics is an antidote to the cynicism that reduces everything to power and to the nihilism that seeks only to subvert and tear down. Its aim is to secure a prosperous future by preserving and building upon the wisdom of the past. At a time when alumni and legislators are fuming at campus activism and the faddish ideologies on display in social media and on the nightly news, conservative support for traditional civic education is something to celebrate. Teaching and studying civics allow us to conserve what is best in our political and intellectual traditions.

Although it is not a value-free social science, neither is it partisan. If anything, it is pre-partisan. Before we can develop a reasonable outlook on the policy issues of the day, we must first acquire knowledge of the character and basis of the political institutions we have inherited and must now steward as Americans. Civic education gives us this knowledge and in so doing prepares us for liberty.

It is a central part of a liberal education in its original sense: the education befitting a free person. It rests on open inquiry, reasoned debate, and freedom of thought and speech, all in the pursuit of truth.

Our students, who will soon be the custodians of the American experiment, deserve nothing less. And the American people, whose prosperity and happiness depend on leaders who understand and affirm that experiment, need nothing less.

Justin Dyer is executive director of the Civitas Institute and interim dean of the School of Civic Leadership at The University of Texas at Austin.