Civic Education Is a Prerequisite for Liberal Education

As Americans begin to familiarize themselves with this new front in higher education—one that can no longer be marginalized or dismissed out of hand—it is my hope that wrongheaded media criticism will eventually give way to the clear positive impact that schools of civic thought are having.

In the past couple of months, thousands of students from across the country began courses offered by new schools of “civic thought.” These new institutions have found homes at some of America’s most highly respected and elite public universities: UNC–Chapel Hill, UT-Austin, and the University of Florida, among others. The growth and spread of these schools has taken on a somewhat revolutionary character.

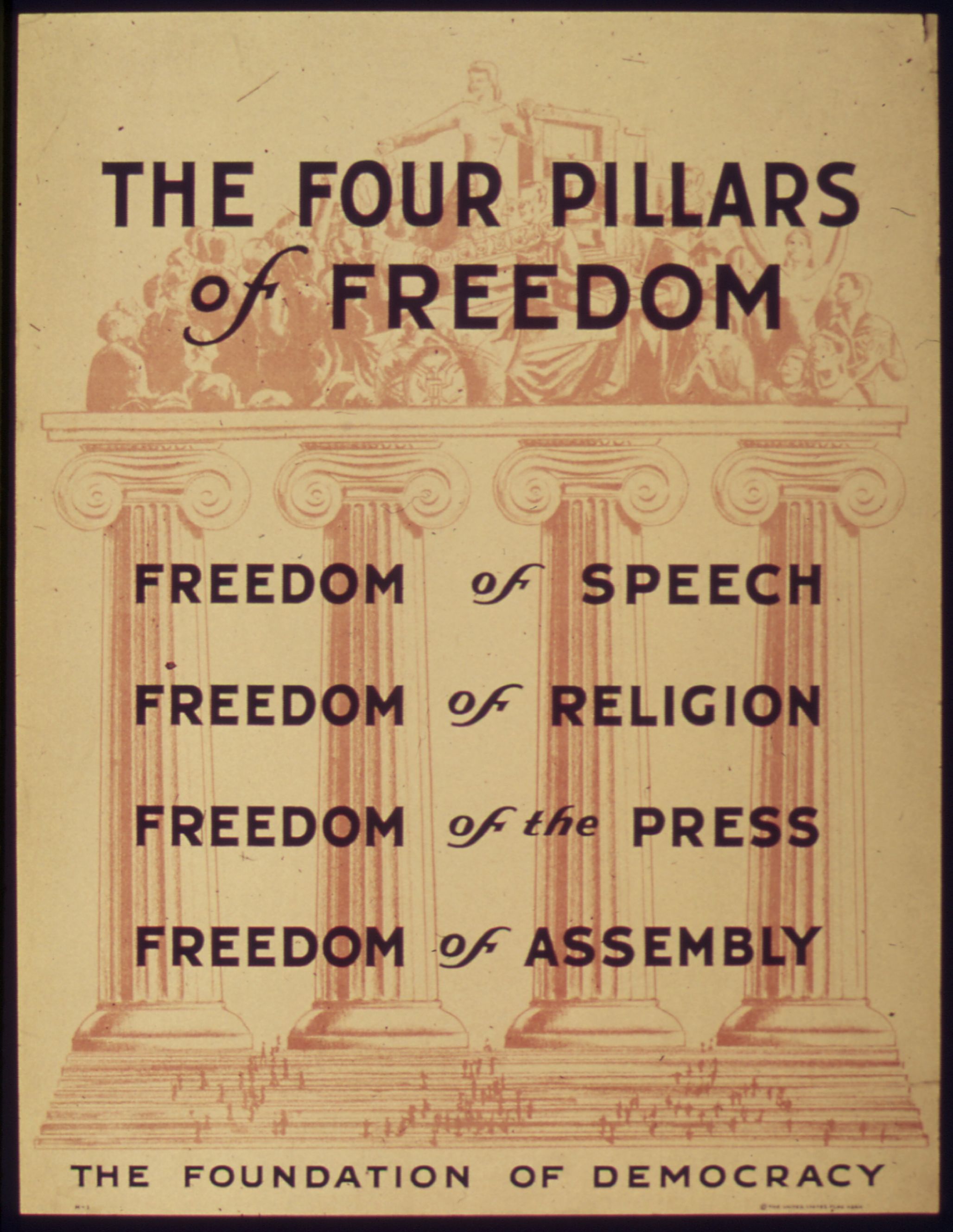

Several state legislatures have taken a direct role in efforts to reshape American higher education by diverting taxpayer dollars to the creation of new, autonomous academic units capable of hiring faculty and setting their own curricula. But despite their growing popularity, these institutions haveprompted criticism from media outlets seeking to expose their supposedly partisan character and their allegedly obscure Western-minded curriculum. In response to these claims, defenders have argued that this is instead a renaissance of civic thought and a good-faith effort to return higher education to standards of excellence that all Americans should embrace.

The Path from Civic to Liberal Education

In May of 2023 I graduated from the first iteration of this new kind of school: The School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership (SCETL) at Arizona State University. It set forth an unconventional kind of education that allowed me to study a variety of subjects, including politics, law, grand strategy and political philosophy—all within the same department. Despite slanderous claims about an alleged right-wing political slant—false allegations that SCETL has faced since its inception in 2018—I felt very early on that there was something quite free, perhaps even liberal, about the breadth of our study, especially when contrasted with my experience in other departments.

And yet critics, from the outset, claimed that liberal education had no place at SCETL. They denounced the school because of its origins in government intervention, and because they believed a focus on the history and thought of Western civilization apparently prevented it from considering “diverse political theorists.” True liberal education, critics claimed, could only occur in the “real” humanities majors or in the university’s already established departments of Political Science and Justice Studies. Only there could students actually come to shed their partisan commitments on behalf of a newfound faithfulness to a vague conception of human rights and equity, established through cold, hard, unimpassioned empirical science and analytical philosophy.

Nevertheless, at my freshman orientation, professors made a compelling case for a new kind of broad, interdisciplinary education that would take its bearings by the question of the ideal American citizen. The school’s curriculum, in order to prepare us to confront and even revive perennial questions about the American democratic republic, would go beyond a mere survey of the founding documents. Our education, they told us, would reach to the philosophical roots of the American experiment by examining the Founders’ various treatments of questions concerning the human condition, the basis of law, and the natural limits of politics.

Yet, because the Founders did not all agree as to the conclusions of these treatments—and insofar as we were interested in attaining a vantage point from which to critically reflect on the basis of the American experiment—our education would need to venture beyond mere civic education. To better grasp for ourselves the character of the discord present at the American Founding, we would have to initiate our own encounter with the same texts and thinkers that inspired the Founders’ most significant reflections.

By not merely taking the Founders at their word regarding uses of philosophical authorities, leaving open the possibility that these authorities had something to say beyond what the Founders attributed to them, we crossed over into the realm of liberal education. In my own case, the additional depth of our inquiry granted me an awareness of how the American citizen might be viewed as the Founders’ earnest attempt to solve what they believed to be the greatest problems posed by the Western tradition. For this reason, it became clear to me how—and why—a liberal education could contribute to students’ civic reflection by deepening their understanding of the rights and duties that characterize their citizenship. Less clear to me, though, was how a civic education could or should contribute to a liberal education.

A Reconsideration of the Requirements for Liberal Education

A year later I declared a second major, this time in the Department of Political Science. Between my experience there, and in elective courses alongside many students from other humanities majors in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, I found SCETL’s education much less partisan and far less narrow than the alternatives offered by ASU. It eventually became clear to me that the cold, hard, and unimpassioned empiricists and political scientists—who bred a body of students with the opposite dispositions—put the cart before the horse. They sought to build before laying the foundation on which to build.

While the kind of liberal education they taught—or what they conducted in its name—did offer exposure to a variety of laws, norms, cultures, and ideologies, it took for granted students’ preparedness to look harsh facts in the face unflinchingly. In failing to distinguish for students the attempt to understand these subjects on their own terms and the attempt to understand them through the latest flavor of twentieth century liberalism, the departments in question prepared students for a total detachment from the American political tradition. Residual imprints that the American story might have left on their souls, or lingering effects of having been reared in the Western world, had to be identified and discarded.

Ironically, this attempt to detach students from the complicated, and at times morally objectionable, tapestry of American political history leads students to be far less reflective about the very basis of their education and their freedom to pursue the truth. It has the effect of leaving students stranded at sea, without knowledge of the very tradition and history that thoroughly articulated the basis for their freedom to depart—however unknowingly—from that tradition and history. That articulation in part comprises the many historical experiences we have of confronting obstacles to the sound application of law and justice, and it supplies the basis for the free and open inquiry that our institutions of higher education can (at least in principle) enjoy today.

Secondly, but perhaps more importantly, students who never cultivate a reflective admiration or love for the American experiment run the risk of adopting a disposition that regards any theoretical or practical departure from the American political tradition as trivial. I refer to the tradition that originated in the first conscious attempt to realize democratic republicanism on a continental scale, and which never took for granted the problems that such scale posed to the task of protecting the natural rights of man. Yet today, when it comes time for the students described above to give a defense of these rights in the political sphere, they either find themselves unprepared to earnestly confront the alternatives to American democracy, or they take a position that unconsciously sacrifices institutional and cultural safeguards that were regarded as crucial to democracy by the political tradition.

If they have yet to understand the American order on its own terms, how can we trust that they will both critique and defend it with the proper care? Moreover, how can we expect them to bear the weight and significance of assessing any alternative to liberal democracy, as is required of students who pursue a true liberal education? It follows that for liberal education to have its greatest impact, it must be taken up by students who hold neither a childish love toward their country nor an outright indifference to it. An analysis of how civic education might contribute to a liberal education ought to begin along these lines.

My own education at SCETL began with two lower-division core requirements for the major. The first was an introduction to political philosophy, and the second was a study of the great debates of the American political tradition, taught by Professor Zachary German. In the latter course, we spent a significant part of the semester hashing out the competing arguments surrounding the abolition of slavery; and through insights I gained in the introductory political philosophy course, I was better able to reflect on both the timeless and the historical character of a few key questions that have permeated the Western tradition.

Through civic education we can retrace the character of that liberal education sought out and applied by the Founders in the design of our democratic republic.

In returning to a well-known debate concerning the nature of justice, recorded by Plato, I was able to see most clearly the crux of the disagreement between Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln. Through Douglas’s proposed local democratic solution to the problem of slavery, his constituency of Northern Democrats and former Whigs, great in number and in strength, would be permitted to preserve the institution of slavery. For Lincoln, no fact of strength or number could be permitted to deny the natural rights of man embodied in the Declaration of Independence. The character and problem of justice, then, seemed to require more than the principle of “one person, one vote.”

In a course I took with the then-director of SCETL, Paul O. Carrese, we engaged in a comparative study of Abrahamic, Hindu, and Confucian philosophy and theology. The adverse reaction that large branches of the Islamic tradition had to the idea of democracy became a central focus of study for much of the semester. Examining the prospect of liberal democracy from democracy-skeptical Muslim perspectives helped me to see more clearly than I had ever before the requirements of liberal democracy, the peculiarity of the basis of our rights, and the historical novelty of the American system that separated church and state.

The Function of Schools of Civic Thought

Institutions like SCETL rightly see American citizenship and the American political tradition as the proper starting point from which to begin a practical education in law, statesmanship, and grand strategy. Through civic education we can retrace the character of that liberal education sought out and applied by the Founders in the design of our democratic republic, keeping an eye on the subtleties they identified in the human condition and on the enduring questions they posed about our nature. Schools of civic thought such as SCETL therefore also prepare us to zoom out from the particular in search of universal truths in a manner that is more conscious of potential obstacles to clear thought and sound judgment. This blend of civic and liberal education keeps the question of our own citizenship in the forefront of our minds, and for that reason it will better prepare us for the task of reassessing the potential of democracy and the health of our society.

Furthermore, the highly practical nature of this education will prepare students for law school, for work in federal and state government, for organizing civil associations, and for leadership in the private sector, among other roles in public life where we are in desperate need of better leadership. Students will learn how to read, write, and speak with a certain prudence attainable only through a deep study of the American political tradition and Western civilization.

These new schools of civic thought will continue to “teach critical minds and to puncture complacency” while urging students “to be both proud of genuine greatness and humble about human imperfection.” As Americans begin to familiarize themselves with this new front in higher education—one that can no longer be marginalized or dismissed out of hand—it is my hope that wrongheaded media criticism will eventually give way to the clear positive impact that these schools are having. I challenge the critics to meet these schools on their own terms—that is, as institutions supporting genuine diversity of thought and intellectual rigor.

Stephen Matter holds a research assistant position at the Jack Miller Center, where he researches topics related to civic and liberal education theory and practice. Previously, Stephen worked as a political consultant on matters of higher education policy and other areas more broadly. He has also worked in the Arizona public sphere at various publications, lobbying efforts, and at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law researching constitutional design. He holds two four-year degrees in Political Science and Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership from Barrett, The Honors College at Arizona State University, and he will soon attend Boston College’s College of Arts and Sciences for a PhD in American Government and Political Theory.