Into the den of other people’s secrets with Maura Jane Farrelly

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Scholar Maura Jane Farrelly to discuss her new book, Compliments of Hamilton and Sargent: A Story of Mystery and Tragedy on the Gilded Age Frontier.

ED: What led you to write your book Compliments of Hamilton and Sargent: A Story of Mystery and Tragedy on the Gilded Age Frontier?

MJF: I wrote Compliments of Hamilton and Sargent because of a dramatic and quirky photograph my mother found in her parents’ house after my grandmother died. My grandmother had written the name “Edith Sargent” on the back of the photograph.

Curious about who this woman was, I did what all good scholars do when faced with a question about the past: I hopped on Google. After narrowing my search a bit, I finally discovered a letter-to-the-editor in the online archives of the New York Times. It was written in August of 1913 by a woman named Edith Sargent who took great exception to the way the Times had covered the death of her husband. According to the paper, John Dudley Sargent had been a “recluse.” He’d killed himself earlier that summer in the valley between the Gros Ventre and Teton Mountains known then as Jackson’s Hole. “I am here to state as a loyal, loving wife that the man was incapable of committing murder,” Edith angrily told the newspaper’s editor. “He was never unbalanced except by melancholia, which does not prompt people to murder their chums.”

The “chum” Edith referred to was a state lawmaker from New York named Robert Ray Hamilton. “The stories to which Mrs. Sargent objects originated among ranchers in Jackson’s Hole who did not like Sargent and Hamilton,” the Times explained in an effort to give Edith’s letter some context. “The stories had to do with the death of Hamilton and the first wife of Sargent. They were to the effect that Sargent knew more about Hamilton’s death in October 1890 than was ever brought out by official investigators.”

The Times reminded its readers that Robert Ray Hamilton had been “the son of Gen. Schuyler Hamilton of this city,” meaning he was the great-grandson of Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first Treasury Secretary. Ray Hamilton had also been “the central figure in a scandal in 1889,” the Times recalled, “in which a woman by the name of Eva Mann and a purchased baby figured.”

Thus began my journey down the rabbit hole and into the den of other people’s secrets that became the setting for this book. The secrets I uncovered soon involved more than just murder, suicide, baby-selling, and a founding father’s family. They also involved bigamy, blackmail, debt, rape, incest, guillotining, corpse-skinning, child abuse, mental illness, and (not to be outdone by any of that) elk-poaching. Suffice to say there were days when I found myself wondering whether this story was one I had any right to pursue and tell.

ED: Why do we need to read your book?

MJF:

I hope everyone who reads this book will walk away from it understanding the extent to which the institutions, values, practices, and laws that animate our lives today and seem to be stable, abiding, and immutable had to become. This simple truth means that the rules that are intensely important to us now because they bring order to our world and direction to our lives will almost certainly change.

MJF: We have become very quick, as a culture, to use the internet to identify and condemn transgressions, large and small, and the people who have committed them – those who have violated the protean norms of our communities or sometimes just failed to embody those norms. And once we have identified the transgressors and condemned them through the internet, their transgressions endure. They can be easily discovered five, ten, even fifteen years later and feel brand-new to the people discovering them.

The three main characters in my book – Ray Hamilton, Jack Sargent, and Edith Drake Sargent – all came from prominent families on the East Coast. They each experienced some form of humiliation after they had violated the rules of their communities. They moved to Wyoming in the late nineteenth century, believing that distance and remoteness would hide their shame. But by the 1890s, the West was no longer a place where anyone could hide. The train went out there. The telegraph went out there. There were AP reporters out there. Places like Laramie and Cheyenne even had telephones.

A forgotten right

MJF: Just as many today are learning that the internet has opened up a vast wilderness of information to exploration and settlement – enabling our transgressions to follow us for years – so, too, did Hamilton and the Sargents learn that technology and the growing power of celebrity journalism made it difficult for anyone in the West to leave a scandal-ridden past behind.

Compliments of Hamilton and Sargent

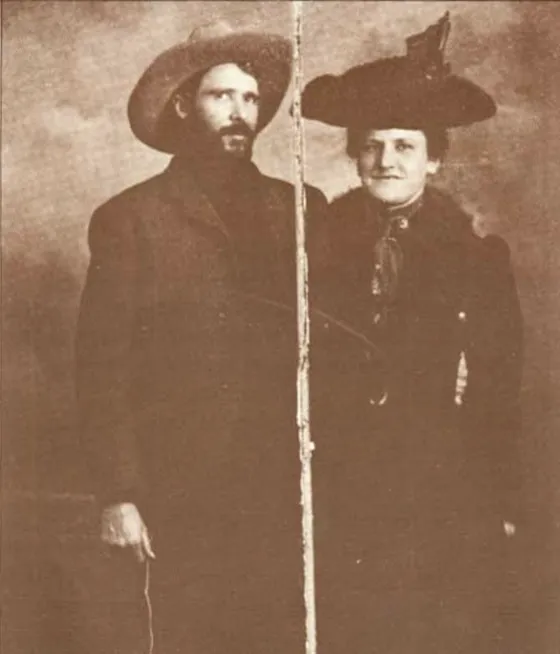

is a story about the early demise of our right to be forgotten – and the sometimes tragic consequences of our inability or unwillingness to approach one another and our values, habits, institutions, and laws with a sense of humility and an understanding of change. If readers feel some sympathy for Ray, Jack, and Edith (Jack and Edith, right) — as I hope they will — then perhaps that sympathy will provoke them to think about how we judge one another in the digital age? Goodness knows I have been provoked to think about this topic.

ED: What is the main argument of your book?

MJF: I guess I kind of laid it out in the answer above – but I should stress that this argument about history and change and humility and the “right to be forgotten” simply serves as a frame for my story. The “meat” of the book, so to speak, is a triple biography that uses the lives of three people to explore the history of the Gilded Age. To understand Ray, Jack, and Edith and the secrets that defined them, the book has to interrogate the world they inhabited, the history that shaped them and the developments they witnessed and participated in that shape the lives of Americans today.

All of our lives are a bit like a room that has been illuminated with a seemingly simple flick of the switch – which is to say there is nothing “simple” about our lives at all. There is a massive and complicated grid behind many of the decisions we make, and as with electricity, the source of our decisions sometimes lies very far away from us.

ED: Writing a single biography seems intimidating enough, but your book presents readers with a “triple-biography.” How does one go about researching and writing a triple-biography?

MJF: When you’re writing a biography, be it about one, two, or three people, I think it’s important that you not assume you understand anything you are reading in the documents you encounter. Question everything. I remember reading one document where a lawyer who represented Jack Sargent’s uncle talked about a “Kearney style lecture.” What the heck could that possibly have been? It would have been easy for me to just let it go and not try to find out — but I’m glad I did try to find out, as it ended up being quite important! You also have to mine your evidence and be open to finding the answers to your questions in creative and circuitous ways. This is particularly important when the people you are writing about are not historically significant figures – they are not people whose names, at least, will be known to your readers before they pick up your book, or people who had a sense of their own place in history (and worked, therefore, to document their lives for you). Jack Sargent was kind of a nobody, although he came from a number of prominent New England families. He did leave a handful of letters and some very small scraps of a memoir behind. But for the most part, I had to look to other people to get a sense of who he was and the forces that shaped him.

More so than any other project I’ve done, this book really highlights the historian’s craft, I think: how we construct the narratives we construct. We are limited by the evidence that has survived the test of time – or, as I found out on more than one occasion, by the surviving evidence that we are allowed to look at.

MJF: I was not permitted to look at Edith Sargent’s medical records, for instance, because of a New York state law from 1972 that says a person’s mental health records can never be made public, no matter how many decades have passed since her death. The law is well-intentioned, and I am confident it has accomplished some good. But it also inadvertently perpetuates the notion that there is something uniquely and deservedly stigmatizing about mental illness. And in my case, it denied me the opportunity to learn about Edith’s struggles from doctors who, presumably, had her best interests at heart (as opposed to the dozens of nineteenth-century journalists whose articles about Edith I was able to read, each and every one of them designed to sell newspapers).

So I spoke about the law and its consequences in my book, and then I explored the treatments and medical philosophies that would have animated physicians at the kind of mental hospital where Edith was kept. She was sent to a homeopathic hospital, which was a little bit different from other types of asylums.

I will admit that my inability to get access to Edith’s records was very frustrating to me at first (and believe me, I did try…). But in the end, I was able to turn the situation into an opportunity. You have to be willing to do that when you’re writing a biography.

ED: What does your book reveal about America’s founding principles and history?

MJF: I have long felt that part of a historian’s job is to be a docent or diplomat. “The past is a foreign country,” as the British novelist L.P. Hartley said. “They do things differently there.”Historians guide their contemporaries through the foreign country that is the past. We encourage our readers to develop relationships with that country’s culture, and we advise them on how to do so. This task requires us to emphasize how the past is different and why. We are obliged to be vigilant about not allowing ourselves or our readers to fall into the trap of assuming that the manners, values, rules, and habits governing our lives today are the same ones that governed the lives of those who came before us.

But a good historian will also remember that we are rarely, if ever the first people in the world to desire the things we desire, fear the things we fear, hate the things we hate, and love the things we love. The world Ray, Jack, and Edith inhabited would be foreign to us in some significant and important ways, were it possible for us to be whisked back to 1879, when Jack first moved to Wyoming (his cabin, right), or to 1890, when Ray joined him there. But I hope Compliments of Hamilton and Sargent also makes it clear that the passions that animated these people are the same passions animating us; the demons that haunted them are some of the same demons.

The principles of American identity that were articulated at the time of the Founding have relevance for us today only because they speak to some of the common, human needs for freedom and self-determination that transcend time and culture.

MJF: Those principles were articulated by men who were products of their time. It is absolutely important that historians interrogate this truth. But it is also important that we not make the mistake of assuming that context is everything. It is a lot – maybe even most of everything. But human nature animates history, too. Human nature moves us forward and backward. And human nature is what America’s founding principles are all about.

ED: Thanks so much for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).