Complicating the Lived Experience of War with Brynne Long

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Brynne Long to discuss her work on prisoners-of-war during the American revolution and her forthcoming article she wrote for the American Philosophical Society. Dr. Long is the 2024-2025 Charles Young Fellow at the U.S. Army Center of Military history.

ED: Tell us a little bit about how you came to research prisoners of war during the American Revolution.

BL: When I was a Historic Trades intern at George Washington’s Mount Vernon as an undergraduate, part of my duties was to write an original research paper. Lacking a topic, I decided to explore within the manuscript archives at the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at the estate. In my search, I found a transcription of a diary written by John Blatchford, a Massachusetts man taken prisoner by the British navy during the early months of the American Revolutionary War. His story of captivity got me hooked on prisoners of war initially. Upon realizing that the scholarship on British-allied prisoners in American captivity is far more limited than that afforded to Patriot prisoners like Blatchford, I shifted my focus to begin filling the gap in the literature.

ED: What made prisoner of war management such a logistical challenge?

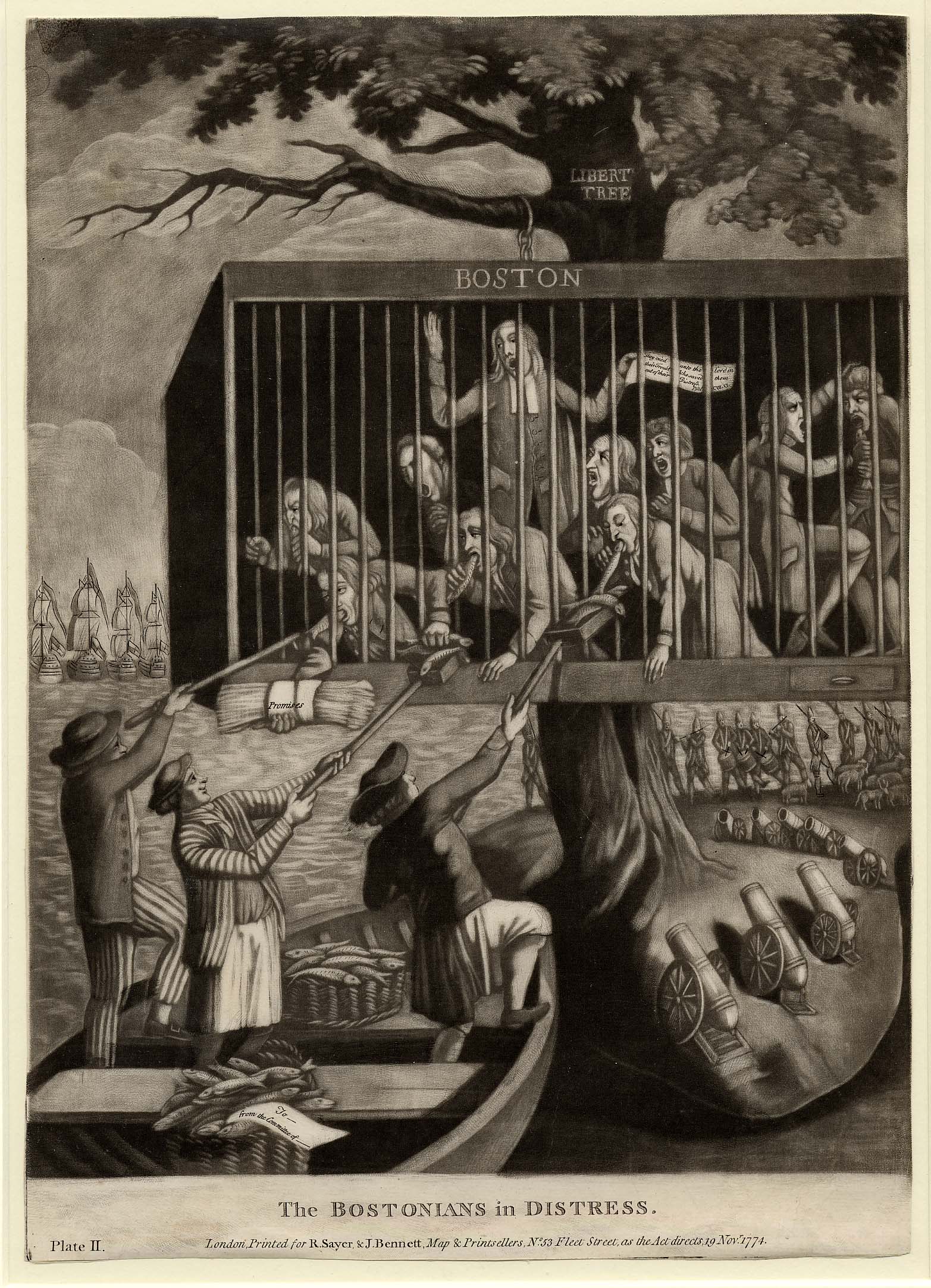

BL: For the Americans, the main problem at the start of the war was the lack of clarity around the nature of the early conflict. Ad-hoc Patriot forces and vigilantes captured British troops in military garrisons and in other small skirmishes before the Continental Congress declared independence. Before there was a formal state of war between Great Britain and America, these prisoners were not technically prisoners of war. Since Congress did not want to prematurely signal a commitment to war by issuing directives in their care, the early administration of these military prisoners was ad-hoc and occurred on the local level in various cities and towns throughout the colonies. When Congress declared independence and later moved to begin standardizing prisoner administration, military prisoners were not only widely dispersed, but administered by various authorities in different ways that proved difficult to consolidate.

Another problem was funding. The standards of civilized European warfare in the eighteenth century obliged belligerents to pay at least some of the costs for their men in captivity. Unfortunately for the Patriots, the British government did not consider America a legitimate sovereignty, a necessary precondition of being afforded such standards. The British delayed repaying expenses incurred in the care and keeping of prisoners, leaving the Americans to foot the bill. In many cases, local governments paid the expenses of military prisoners and looked to state authorities for reimbursement. State governments increasingly resisted paying for military prisoners as the war lengthened, and Congress could not itself pay for prisoners owing to its inability to tax the states. Shortages of provisions for prisoners resulted from these circumstances.

Occupy your street

ED: One of your most fascinating arguments stems from how the Continental army “was an occupier in its own right.” To what extent did American colonists feel that way, especially if (or when) they were confronted with the prospect of hosting prisoners of war?

BL: When I talk about the Continental Army as an occupier, I’m referring to its usurpation of responsibilities held by provisional wartime authorities, mainly Committees of Safety, at the start of the war. Committee members often appreciated the temporary nature of their organizations and in some cases even hastened their disintegration in the interest of establishing a new American government that more closely resembled colonial political traditions and norms. The behavior of colonists themselves suggests that many resisted this “return to normalcy” impulse. Provisional wartime governments were more politically radical than the colonial legislatures that preceded them. Committees of Safety embodied the radically democratic spirit of the early war years, allowing early Americans significant influence in local wartime politics through them. This influence extended to prisoner administration in regions that hosted prisoners of war.

Early Americans in host communities had a lot of say over what prisoners could and could not do. This began to change when the Patriots established constitutional state governments, foreclosing upon the necessity of provisional governments and significantly curtailing the direct political influence of early Americans.

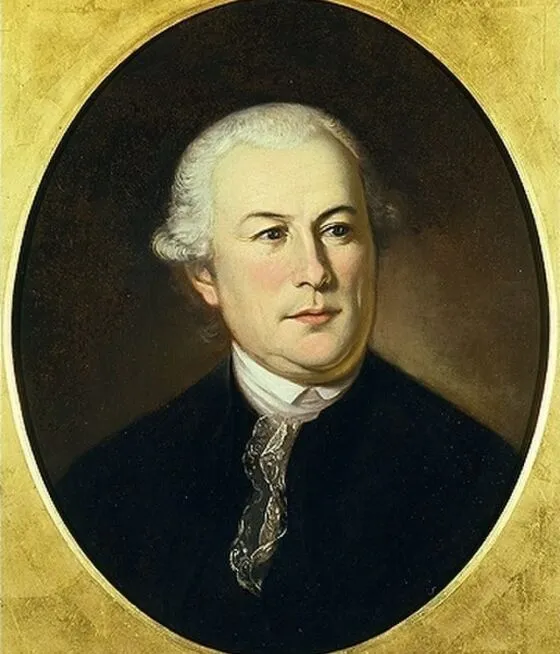

BL: Concurrent with these governmental developments, Congress established the Department of Prisoners in 1777 to begin standardizing prisoner administration under the auspices of the Continental Army. The nation’s first Commissary General of Prisoners Elias Boudinot and his deputies encountered individual and community-wide resistance to their authority in many host towns and cities. Unlike during the earlier years of the war, inhabitants in host communities could no longer pressure their local Committee of Safety to pass prohibitions or allowances regarding prisoner populations. Such power was transferred to the Department of Prisoners, a change that I characterize as an “occupation” of existing governing functions.

ED: Another intriguing insight you discuss throughout your piece is the idea of “prisoner allowances.” What were prisoner allowances, and did these allowances influence the post-Revolutionary world?

BL: Allowances variously empowered prisoners to travel, seek their exchange, and most importantly, labor for additional subsistence. The ability to labor had a transformative influence in host communities and for prisoners themselves. Owing to the logistical and financial difficulties of prisoner administration detailed in my second answer, provisions for British-allied prisoner populations were often limited. For prisoners in American captivity, earning a wage could mean the difference between life and death. Infamously, many British-allied prisoners in the Convention Army faced starvation in captivity. The unique terms of their surrender, negotiated at the conclusion of the Battles of Saratoga, limited the ability of the prisoners to labor. Because the Convention prisoners represented a population ineligible for exchange, the states saw only expenses, no value, in permitting their admission on any terms. The prisoners endured several grueling marches between states until the end of the war, without a home base. Conversely, stationary prisoners in Pennsylvania host towns including Lancaster had more opportunities to work, providing for themselves, and in some cases their families who traveled with them. Prisoner labor also helped alleviate the economic burden of war on host communities, many of which lacked some portion of their laboring class, away fighting the Revolution.

Elias Boudinot, POW Czar

ED: What role did Elias Boudinot play in prisoner administration?

BL: Elias Boudinot was the nation’s first commissary general of prisoners. Washington appointed him to serve at the helm of the Department of Prisoners with the expectation that he would standardize prisoner administration. Washington hoped that such a standardization would allow him to better control the treatment of British-allied prisoners in captivity, giving him leverage to alleviate the suffering of American prisoners in British captivity. Boudinot was admirable for his embrace of Washington’s sympathetic plan. He was also myopic. He did not try to understand the perspectives of those early Americans who resisted his authority on their own and through their state and local governments. Interpreting their actions as intransigence and a lack of Patriotic fervor led Boudinot to a very bitter view of the American public’s sincerity about supporting the war effort.

ED: Not to give you another project…but do you have plans to expand your work on prisoners of war to the Southern colonies?

BL: Yes! This project is undergoing an extension at the moment, both temporally and geographically. My sense is, and secondary sources seem to verify this, that the southern colonies did not have the same long history of popular influence in governance and military affairs that the New England and some middle colonies, particularly Pennsylvania, had. This lack rendered the radical democracy of Committees of Safety more of a novelty than a culmination of colonial precedent. For this reason, southerners did not rush to defend their recent political empowerment when the provisional wartime governments that provided its vessel began disbanding. I am in the process of investigating the veracity of this sense through primary source research in the governmental records of the early southern states. My temporal expansion is backwards into the colonial period, where I plan to investigate the regional similarities and differences in colonial martial culture. To regionally various degrees, early American settlers controlled local militias in their offensive and defensive operations. This experience gave precedent to the influence in military affairs that revolutionaries defended in their resistance to the Department of Prisoners during the Revolution.

ED: What has your work on prisoners of war during the Revolutionary War taught you about American history?

BL: My work on prisoners of war during the Revolution has done nothing if not complicate my understanding of the lived experience of warfare. I started this project with an advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy from Deputy Commissary of Prisoners for New England Joshua Mersereau in which he is asking inhabitants of host communities to return British-allied prisoners of war to his care. Mersereau was of a mind with Boudinot; he intended to use the prisoners as leverage to free Americans in British captivity. Despite this admirable intention, further research revealed that he and other deputies in the Department of prisoners were often reduced to pleading with his compatriots to relinquish prisoners. Through my work, I have learned that early Americans did not see prisoners the same way as officials like Mersereau. Democratic influence allowed early Americans to variously economically and socially recast prisoners as laborers, friends, and even romantic partners. The apparent lack of patriotism among host communities was actually an expression of these new relationships. More importantly, it reflected the radical democratic promises of the early Revolution, quickly tamped down by reactionary conservative impulses.

ED: Thanks so much for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).