An interview with Timothy C. Hemmis

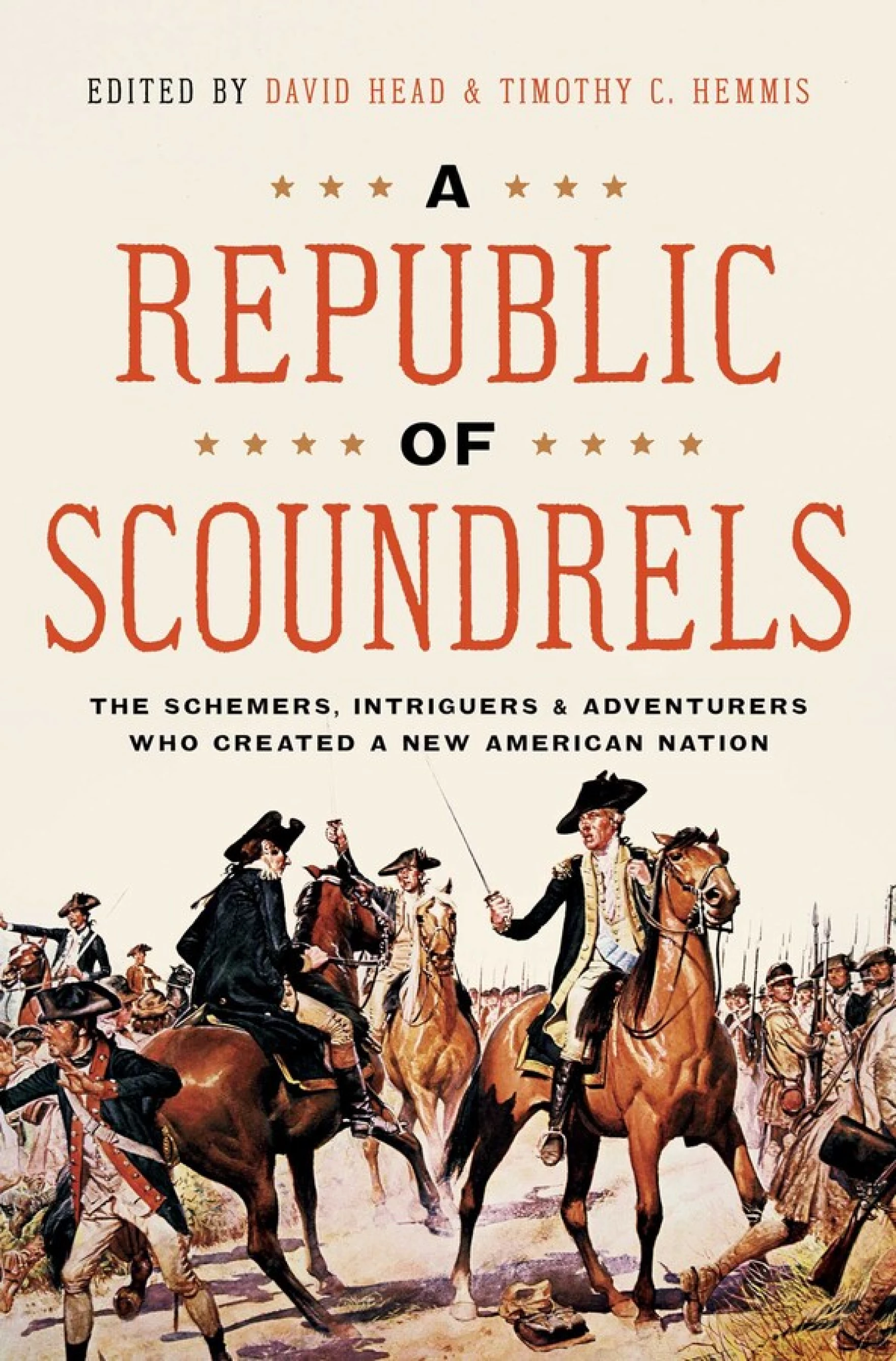

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Timothy C. Hemmis to discuss his new book, A Republic of Scoundrels: The Schemers, Intriguers, and Adventurers Who Created a New American Nation.

A grand experiment that could come crumbling down

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

TH: Originally in High School I wanted to be an architect, but calculus was not my strong suit, so I chose my passion of history. I always had an interest in history, and I loved to travel to historical sites and museums as a kid, but I had a history teacher, Mr. Larry Sweet, who inspired me to think about being a teacher. So, I decided to become a History Major at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania.

By my sophomore year, I really found my passion for American History, and I remember in an advising meeting with my faculty mentor, Dr. Ronald L. Spiller, he asked me what I wanted in my career. I boldly said I wanted his job.

So that set me on the path of being an Early American and Military Historian and college professor. With his mentorship, I attended my first Society for Military History conference during my first year in the master’s program. From there I attended The University of Southern Mississippi for my Ph.D. in American History with a focus in Early American and War and Society. There I studied under Dr. Kyle Zelner. In 2015, I graduated with my Ph.D. I only made it through because of the mentorship and guidance I had along the way from my teachers and professors.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

TH: The nature of my current job is that I am an Americanist, so I often teach a wide variety of American History courses from Colonial America to the Civil War, and to history of the American West. However, my research focus has been on the Revolutionary America (broadly defined). Much of my research focuses on individuals that lived and operated in the American borderlands. Many of the people that I write about have military connections but did not hold combat commands. Much my current research fits more in the area of War and Society, however I have done some scholarship on The Legion of the United States and Anthony Wayne.

I really became interested in American Military History as I was interested in World War II and the Civil War History as a kid. But as I became a historian –I realized those subfields were oversaturated with scholarship. So, I gravitated to first the Seven Years’ War and then The American Revolution. I am still in those areas of research as I have found the Revolutionary Era (including the Early Republic) is a fascinating topic to teach and to research. One of my burning research questions revolves around the development of American identity and national loyalty in such a period of turmoil and change. In much my scholarship that question has driven research.

Burr’s civil war

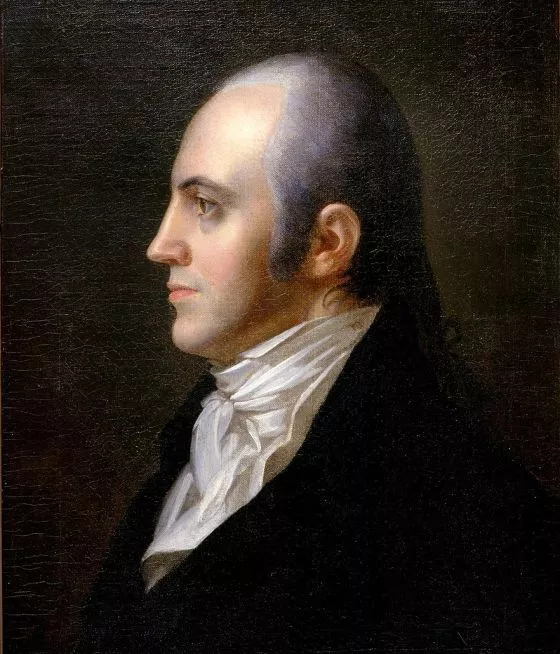

ED: Tell us a little bit about Aaron Burr’s “failed insurrection,” and what his actions reveal to us about American identity in the decades immediately following the American Revolution?

TH: Aaron Burr is a name that has become more popular in recent years because of the musical Hamilton. There is still much to debate about Burr’s Conspiracy(s), but many Americans have little knowledge of the events that almost ripped apart the American Republic in 1807. After the murder of Alexander Hamilton, Burr went on a western tour of the country and he began plotting several different schemes including carving out western lands for separate country, filibustering in Spanish lands, even raising a frontier army and marching on Washington DC. Burr hoped to use the anger of the frontier people as a motivating force like it did during the Whiskey Rebellion. However, Burr miscalculated the national loyalty of many Jeffersonian republicans along the American frontier.

Even though Burr failed in his plots, his actions and his supporters divided the nation. Because the Civil War overshadows the events of Burr’s Conspiracy(s), we do not get to see how it shaped the American story or even really remember it. It is often a curious footnote in history; however, it really demonstrates how fragile the Republic is and also it laid the groundwork for populist politicians such as Andrew Jackson.

Easter eggs

ED: What was your favorite research rabbit hole, and why?

TH: Often in my research, I will find minor little easter eggs that connect me to other events. For examples, while doing research for my dissertation I kept coming across names like James Wilkinson (left) and Thomas Hutchins. Wilkinson was a major figure in the Early Republic and probably deserves more attention, but I kept running across these men who I called scoundrels. So I kept thinking there would be a good book about Scoundrels of the Early Republic, but their papers were all over and it would have taken at least fifteen years to compile the research myself. So during the COVID pandemic and shut down, I hatched the idea of an edited collection with Dr. David Head. Hence how A Republic of Scoundrels was born. But during research, I will stumble across names and keep following down those paths.

TH: Additionally, I have traveled and visited some historical sites that spark a question. Recently, I traveled to New Mexico and visited Jemez Springs and the Pueblo ruins. At the ruins there was a church that was built in 1621. The same year at the First Thanksgiving in the Plymouth Bay Colony. So, I have become fascinated with the Pueblo Revolt and reading anything I can on it in my free time. Although it does not directly relate to my current research it has expanded my teaching and knowledge on another part of Early American History.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

TH: My scholarship and the historical question about the development of the American identity encompasses the American founding principles because they explore that origin story.

American often take for granted the liberty and freedoms we have with little thought as to how they came into being or even how fragile they are. I truly hope my scholarship highlights the forgotten parts of the American narrative, but also show how it can be destroyed so easily. Whether it is the Whiskey Rebellion, the Aaron Burr schemes or the American Civil War– the American Republic is a grand experiment that could come crumbling down. Whether it is my scholarship or my teaching – I want to highlight the importance that we all need to care for our nation and understand our history but also how we can participate in this grand experiment today.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about the American history?

TH: This question is tough, because I could say many different things about American history, which I deem important. The one thing, that keeps coming up recently is how many people dismiss anything that happened before the Civil War.

Many people do not realize how much history there is before the Civil War or even before the American Revolution. The Colonial period is often neglected in classes for the sake of time. But there was at least 200 years of history before the American Revolution.

TH: Often these colonial histories were multinational – English, French, Spanish, Dutch, and even Swedish. That is just the European perspective, once you add in the history of Native America, which goes back even further. Time is a hard concept to grasp, and we gravitate to modern times and often history in living memory. Hopefully people can understand that Early American History is vast and did not just start in 1776 (although that is a very important year).

ED: Thank you for your insights and time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).