An interview with Scott C. Miller

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Scott C. Miller to discuss his work on financial panics throughout American history as well as the aims of the Project on Democracy and Capitalism (led by Dr. Miller). Dr. Miller is also an assistant professor at the Miller Center at the University of Virginia.

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

SM: First off, I don’t come from an academic family. My family certainly valued education, but they are not traditional academics in any way, shape, or form. I’d say the same about history—I was always interested in it, but not as an academic discipline, just as something that existed. The first moment where I got a glimpse of what history could be as an academic pursuit—I’m sure you’ve heard many stories like this—was in a freshman US history survey class. It was the second half of the US history survey at the University of Colorado, where I went for one year before I transferred. There were 800 other kids in the class, and the professor, Thomas Zeiler, was talking about the McCarthy hearings.

What I found incredibly interesting was that in every other class, when you have 800 kids in a massive lecture hall, you start hearing rustling five minutes before the class ends, people start moving around, and then once the class is over, they’re out of there. But what blew me away about this session on the McCarthy hearings was that the professor finished, and I looked up at the clock—it was eight minutes past the end of class—and I hadn’t even noticed. I hadn’t moved. And that was the first moment where I thought, “Okay, this is something different from just the interesting nature of the past. There are compelling arcs to these stories that are relevant in ways we don’t normally think about them.” It made me realize that this could be a job where you’re involved in that kind of exploration. From that moment on, I started thinking about ways to maybe do this for a living, though it was never necessarily a straight line. But that was the moment I thought, “Okay, I think I want to do this, if I can.”

ED: At a certain point, all scholars must specialize in a specific subfield. How did you decide on your subfield? And when was the first time you realized you were an expert in that area?

SM: Yikes. So, I went through undergrad and graduated as a history and political science major. I was never particularly interested in early America. I took a political philosophy class in my last semester of undergrad. My interests had been in British history, though not in a very sophisticated way. In that class, we read the classics—Burke, Rousseau, Locke, and so on—but we also read the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists.

That got me interested in how these ideas manifested in the American Revolution and how abstract concepts came to practical conclusions. It was the intersection between ideas and real-world events that really caught my attention, and as we’ll probably talk about later, it’s been central to my career and how I think about history.

SM: At that moment, I realized I knew nothing about early America and that I should, but unfortunately, I was already done with undergrad. So, I just started reading on my own. After finishing school, I moved back to Denver, Colorado, and started working for a small company that focused on World War II aviation history, which opened a lot of potential avenues for me. But in my spare time, I began reading books on early America.

What really got me into economic and business history was a surprising turn of events. Let me preface this by saying that the two worst grades I ever got in my life were in introductory micro and macroeconomics—one was a C- and the other a D+. Wild, considering what I do for a living now, but I had no interest in economics at all. However, I happened to be in London when the global financial crisis broke out in 2008. My wife and I had just gotten married, and we were visiting the British Museum or British Library.

I clearly remember coming up a long escalator from the underground in London. At the time, there were still newspaper stands, and I’ll never forget seeing headlines like “Dow falls 777 points.” I knew that was bad, but I didn’t quite understand what it meant. We walked around the city of London, and it felt like I was seeing people in really nice suits who looked as disoriented as I felt on 9/11. It was a sense of panic that was unmistakable, but I had no idea what was happening. That was the moment when I thought, “I need to understand what’s going on.”

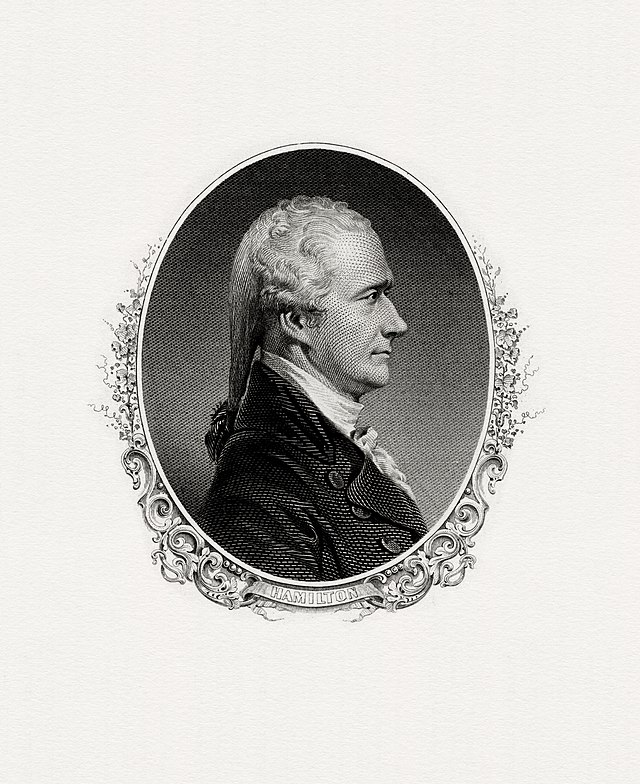

I was also reading a book on Alexander Hamilton at the time, and coincidentally, I was reading about him dealing with America’s first financial crisis in 1791-92. I thought, “This sounds eerily similar to what’s happening right now in 2008.” That moment set me on the course I’m on now. The panics of 1791-92 had been discussed and understood a bit, but it was that period that became the focal point of my studies. It’s the thing I know better than anything else, and it charted the path I’m on today.

ED: Most Americans know about the 1929 stock market crash, and of course, 2008-2009 is fresh in people’s minds, but are there any other major panics in American history that most people don’t know about? Are there any crises that don’t get the attention they deserve but should?

SM: I’m wrapping up a class that I teach at Darden called “Financial Crises and Civic Reaction,” where I cover about 22 financial crises, going back to 1719 and extending to the present, across seven or eight countries. It’s the pride and joy of my career; I love it. But yes, I would definitely recommend a few that people should pay more attention to. Let’s say one from each century.

Ending the first panic

SM: The first is the Panic of 1791—America’s first financial panic. It’s the first bailout in American history. It’s also the moment when Alexander Hamilton effectively creates the playbook for modern government intervention in financial markets during a crisis. He did it about 70 years before Walter Bagehot codified it in his famous book, Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market. What’s interesting is that the reason we don’t really know much about this panic is that Hamilton did such a good job of extinguishing it. It was a very scary time, and people were really nervous, but Hamilton and his team came together over a weekend in August 1791 and developed a plan to stave off absolute collapse before the markets opened on Monday. They did this by injecting what would be the equivalent of hundreds of billions of dollars into the financial markets. There are many reasons why this is important, but I would say the biggest reason is that if it had gone a different way, the American project could have been very different from what we know today.

SM: Moving on to the 19th century, I’d point to the Panic of 1857. If you talk to people who really know about financial crises, this one is often seen as the first modern financial panic. It’s the first time you see the emergence of a sophisticated and modern shadow banking sector. There was an overinflated and poorly managed shadow banking sector alongside macroeconomic problems, like agricultural crises, and geofinancial issues, like the Bank of England raising interest rates, which drained capital out of the U.S. very quickly. This led to a liquidity crisis and a scarcity of capital. It’s a very modern financial situation, and it’s happening in the shadow of the run-up to the Civil War, with issues like Dred Scott and the Kansas-Nebraska Act contributing to the unrest. So, you’ve got a mix of geopolitical, social, and financial problems coming together, which ultimately sparked the panic.

ED: How about the 20th century?

SM: Ah, the 20th century! This is a case I inherited from the legend, Bob Bruner, former dean of Darden. I was lucky enough to work with him during grad school. He developed this course on financial crises and civic reaction, and when I took it over, I was looking at the syllabus, thinking “That one looks good, that one looks good,” until I came to the 1971 crisis. I thought, “I don’t really know much about this one. Maybe I’ll replace it with something more interesting.” But the more I’ve gotten into it, the more fascinating it’s become. This crisis is centered around the collapse of the Bretton Woods system.

Richard Nixon closing the proverbial gold window… and everything that went on from that. This moment was, dare I say, the most important in the 20th century. The reason I say this is because it marked a fundamental and structural paradigm shift in how financial markets work—money was no longer tied to a finite commodity. That’s a huge change in the world.

SM: After World War II, under the Bretton Woods Agreement, currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, but the U.S. dollar itself was still pegged to gold at a fixed rate. Nixon’s decision to sever that tie and end the gold standard marked the moment when the U.S. dollar became “gold,” not just an intermediary. That’s a massive shift that explains much of how modern financial markets work, but it often gets overshadowed by Watergate and the stagflation of the 1970s. As a crisis, it was monumental, and I think a lot of people don’t know much about it—but it’s worth diving into.

ED: Now, let’s talk about the Project on Democracy and Capitalism. What is the mission, and what type of events do you put on?

SM: Absolutely. The project is housed at the Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia. The mission is to explore the relationship between free people and free markets and to better understand how democracy and capitalism interact with one another. We focus on this because these two ideas—democracy and capitalism—are often treated as political signifiers in today’s climate. But in reality, there’s a very deep, intricate relationship between the two that spans centuries, and we must understand how and why they work together—or don’t. The goal is to look at how these systems coexist, where they work well, where they don’t, and how we can improve their interplay.

The project has three main pillars: policy, teaching, and research. I’ll walk you through each. While the policy pillar is still the least developed of the three (the project has only been around for about two and a half years), we plan to do a lot of policy-focused events in the future. For instance, next fall, we’re hosting a symposium that will tackle the question, “What is the optimal industrial policy for the United States?” The idea is to bring together leaders from the private sector, the public sector, think tanks, and academia to figure out what such a policy might look like. Both sides of the political aisle have embraced some form of industrial policy in recent years, so we’ll debate what the best way forward is.

We also do a lot of work on the teaching front, both in higher education and K-12. For example, our “Democracy and Capitalism Teachers Institute” is a summer program where we bring high school teachers from around the country to the University of Virginia for a week of case studies, lectures, and working groups.

The aim is to give teachers the tools and knowledge to bring the concepts of democracy and capitalism into their classrooms.

This past summer, we had teachers from five or six states, and we’re partnering with JMC on the upcoming summer program. What’s especially rewarding is that after the program, some teachers bring their students to the Miller Center for a day of case studies, just like the teachers participated in, and they do really well. It’s inspiring to see how they take what they’ve learned and share it with their students. Finally, we do a lot of research, but a couple of projects I’m particularly excited about include:

A book coming out this summer, edited by myself and my colleague Sidney Milkis, called Can Democracy and Capitalism Be Reconciled? The volume contains 24 essays from scholars across nine academic fields, exploring topics like the nature of democratic capitalism, climate change, political polarization, monopolization, and inequality.

We are also building a “Capitalism Index,” a major research initiative that seeks to quantify capitalism by looking at how well countries implement various elements of capitalism. This index is inspired by democracy indices from institutions like The Economist and V-Dem out of Sweden. What we’re trying to do is track the elements of capitalism that different countries do well, and how those elements correlate with different outcomes—everything from GDP per capita to social mobility to climate policy. It’s an ambitious effort, and one of the key takeaways we’ve found is that countries you might think of as highly capitalist often aren’t, while countries you might not think of as capitalist are more so than you’d expect.

We also want to make this data accessible to the public through a digital platform where people can interact with the data, adjust variables, and see how different elements of capitalism correlate with different national outcomes. It’s about providing a deeper, more nuanced understanding of capitalism—not just as an abstract concept, but as something that has real-world consequences.

Those are some of the highlights, but there’s much more going on.

The project is growing, and we’re very passionate about the work we’re doing to help people better understand these two fundamental elements of liberal society: democracy and capitalism.

ED: Not many Americans have heard of the 19th-century southern public intellectual George Fitzhugh, and with good reason. Why has George Fitzhugh’s influence on 19th-century thought and his advocacy for slavery as a “positive good” disappeared from our national consciousness, and what might his ideas reveal about the deep and complex nature of American intellectual life during that era?

SM: Ultimate credit here goes to another UVA legend, Gary Gallagher. I took a 19th-century literature class with him, and he assigned George Fitzhugh. I don’t think I’ve ever read anything that blew my mind more than Fitzhugh’s Sociology of the South and Cannibals All!, his two major works. For the record, George Fitzhugh was exactly what you described: he was the public intellectual of the antebellum South.

The most popular pamphleteer of his time, George Fitzhugh was so influential that I came across something which said that if his name was on the cover of DeBow’s Review, it could increase the number of issues purchased by 100,000 copies. He was that well-known. He really shaped the argument for what the South should be.

The level of disdain Fitzhugh had for both democracy and capitalism is absolutely wild. He was overt in his critique, which is fascinating. Meanwhile, you’ve got someone like Karl Marx writing over in Germany, thinking he knows what’s going on—then you’ve got Fitzhugh, saying, ‘No, this is what the South should be. This is true freedom.’ In essence, he was parroting Marxist rhetoric, but from a very different perspective.

What’s particularly interesting about Fitzhugh is that he articulated a version of socialism as the only true democracy. When I say socialism, I don’t mean social democracy, but rather Marxist socialism. Fitzhugh was the voice of the South in this regard. That’s what I find so intriguing: there have been many books written about slavery, capitalism, and related themes, and I respect a lot of them. However, when you look at how people at the time were thinking, I think there’s real value in what Eugene Genovese wrote in the 60s and 70s. Genovese, a Marxist at the time, argued that slavery wasn’t capitalism—it was something else entirely. Fitzhugh, for his part, was clear: democracy and capitalism cannot coexist, and in fact, they should not. He believed that economic freedom simply allowed the strong to oppress the weak and that liberal political systems were too passive or corrupt to correct this. He argued that a very strong state was needed—one that would redistribute wealth and reinforce the rights of the strong to enslave the weak. By doing so, it would create a utopian system in which everyone would be taken care of.

Most Americans today would not recognize this as part of their past. If you described it as something coming from Germany or France, they might believe it. But this was the predominant public intellectual of the antebellum South making these arguments.

SM: I wholeheartedly encourage people to read Fitzhugh’s work. It won’t take long—his writings are short pamphlets. But the long and short of it is that there was not a consensus about capitalism at the time. In fact, leading into the Civil War, a significant portion of the country believed that neither capitalism nor democracy should exist.

This idea connects to the ‘fire-eaters’—those in the late antebellum South who thought Jefferson was too soft on slavery. They argued that Jefferson didn’t fully understand the world they wanted to create.

I mean, the ultimate point I want to make is that I live in Virginia now. I’m originally from Colorado, so I’m a Westerner, not a Yankee, so to speak. What I recommend to people who want to understand how the antebellum South fits into this discussion is to read the Cornerstone Speech by Alexander Stephens. I have my students read both that and other related texts, and it absolutely blows their minds. What Alexander Stephens wrote was essentially the Confederacy’s Declaration of Independence. His argument was that, while Jefferson and the other Founders believed ‘all men are created equal’—and, yes, they really did believe that—he argued they were completely wrong. The Confederacy, he said, was building a state based on the exact opposite premise. And that’s what was happening.

Fitzhugh’s writings are very similar in that respect, though his emphasis is slightly different. When you go back and read these texts, it’s striking to see how radically different this worldview is from the one that most Americans are familiar with.

ED: Let’s talk about the Gilded Age because I’d like to know more about that period. I’m not saying, ‘Please teach me everything about the Gilded Age right now.’ Tempting, but no! When you hear the term ‘Gilded Age,’ what does it mean to you, especially as someone who has studied the period? What does the Gilded Age really represent to you?

SM: Oh, my gosh, that’s a phenomenal question. I would say the Gilded Age is the period when Americans became comfortable with bigness—whether that be big government, big business, big religion, or just bigness in general. For a long time, Americans were very much like British Whigs in believing that anything of great size was dangerous and corrupt. I think we can largely point to the Civil War as a turning point for this shift, but nonetheless, Americans started to embrace bigness in ways they hadn’t before. Not only did massive companies begin to emerge, but massive fortunes were being built in ways that had never happened before.

And, you know, as someone who teaches at a business school, I’ll be honest, I don’t necessarily have a problem with people making money. But the big thing I point out is this: if you look at the mansions of the early republic—like Mount Vernon or Monticello—they’re decent in size, but compare them to their British counterparts, which were these huge estates. Think about Thomas Shelby’s mansion in Peaky Blinders season three—it’s not even close! Those early American homes are like outhouses compared to British estates. Once you get into the Gilded Age, though, you start seeing mansions built that rival the grandeur of monumental British country estates.

And, you know, being here in the Philadelphia area, I’d bet that 20 minutes north of where you are right now, you’ll find the remnants of these vast estates in the northern suburbs—Melrose Park, Elkins Park, etc. Shout out to my dear family who live up there and showed me these places—Deb and Dave, you’re the best. These estates are massive—much larger than anything we even have today.

So, in my view, the Gilded Age marked a fundamental change in American society, where people became much more comfortable with the idea of bigness. But I also think the Gilded Age was much more heterodox in terms of ideas than people often give it credit for. You tend to hear about big government vs. small government, big business vs. small business, the working class vs. the aristocracy. But you had a mix of ideas that don’t really fit onto our modern political spectrum in any way, shape, or form.

ED: Thanks so much for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).