An interview with Sam Young

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Samuel Young to discuss his work on religion, identity, Martin Luther, and Protestantism during the antebellum era. Dr. Young is an Assistant Professor of History at Indiana Wesleyan University.

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

SY: Growing up, I always loved school. I came from a big family where my parents and siblings were always reading. A steady diet of books like Johnny Tremain, Chronicles of Narnia, and Redwall, all predisposed me to perk up during Social Studies classes. Initially, history was like a puzzle: “Here’s a different time and place; now try to make sense of it.” As I grew older, I came to appreciate the ways in which the historical context and impersonal forces that shaped past peoples and events also shaped me, my experiences, and my understanding of the world. Once my understanding of history moved beyond raw dates, figures, battles, and maps to a reflection on human experience, I knew I wanted to spend my life reading and thinking about the past. When I went off to undergrad, I was firmly set on being a high school history teacher. I loved my classes and professors, and when I graduated, my advisor recommended that I teach for a couple of years and then think about going to graduate school, and that’s what I did.

I’m grateful for the years I taught high school. I found myself drawing on those experiences throughout graduate school, and they made my transition to a teaching-heavy professor position fairly seamless. But it took me a while to develop the writing and research practices needed for historical scholarship. Teaching is still a large part of my work, but the more I write and publish, the more I enjoy the work of being an active historian, in addition to my history teaching.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

SY: I study the history of religion and culture, especially in the United States. I grew up in a religious home, and at a certain age began asking questions about the similarities and differences between our congregation and the other churches in town. As a young teacher, I picked up a copy of Nathan Hatch’s Democratization of American Christianity and it blew my mind. Though it’s primarily a study of American religious culture in the decades after the founding, Hatch charts impulses within American Christianity that have endured to the present, characteristics that I could recognize had informed my own religious experiences. I love studying religious history precisely because religion is inextricably linked with all other aspects of human life: politics, economics, gender, race, community formation, conflict, and local and national identities.

Most of my research revolves around questions of religious and national identity, particularly the ways in which Americans have interpreted historical figures, movements, or events from the Christian past in light of their contemporary concerns and context. There’s been some incredible research in the last few decades about how Americans have used (or misused) the legacy of figures like the Founding Fathers or Greek and Roman authors from the classical era. In a similar vein, my work examines how Americans of all faiths imagined and reimagined men and women from the Christian past as part of the nation’s history, and leveraged their larger-than-life personas and ideas to address the social and political issues of their own eras.

ED: What was been your most fruitful research rabbit hole, and why?

Where’s Waldo?

SY: One of my first research breakthroughs came when I was an MA student, trying to figure out what my project would be when I got into a PhD program. I was reading a lot of Philip Schaff, a German-trained historian of Christianity who came to the United States in the 1840s and had an educated, outsider’s perspective on American politics, religion, and culture (not unlike de Tocqueville). In his early writings, Schaff criticized the ways in which Americans read and thought about history, and he had a throwaway line about Americans believing all these unhistorical myths about the Waldenses. The Waldenses were a medieval religious movement that derived from Peter Waldo, a twelfth-century merchant who became interested in vernacular scripture reading and serving the poor. Persecuted by the Roman church, the Waldenses hid in the Italian Piedmont until the Reformation when they were incorporated into Protestant churches. Schaff noted that many Americans believed these Italian Waldenses had actually begun in the first century with the apostle Paul, rather than in the Middle Ages with Waldo. Reading this, I asked myself: what’s Schaff talking about? Did Americans really believe this? Why?

SY: After a few years down this rabbit hole, I found that antebellum American Protestants latched on to the idea of a pure Protestant church in Italy that could be traced back to the apostles in part because it gave them a powerful argument against the apostolic claims of Roman Catholics, whose presence in America was on the rise due to immigration. Tracking down the context to a throwaway line in an obscure publication from the 1840s became the basis for one of my first publications.

ED: Describe your favorite primary source that you encountered while researching your work.

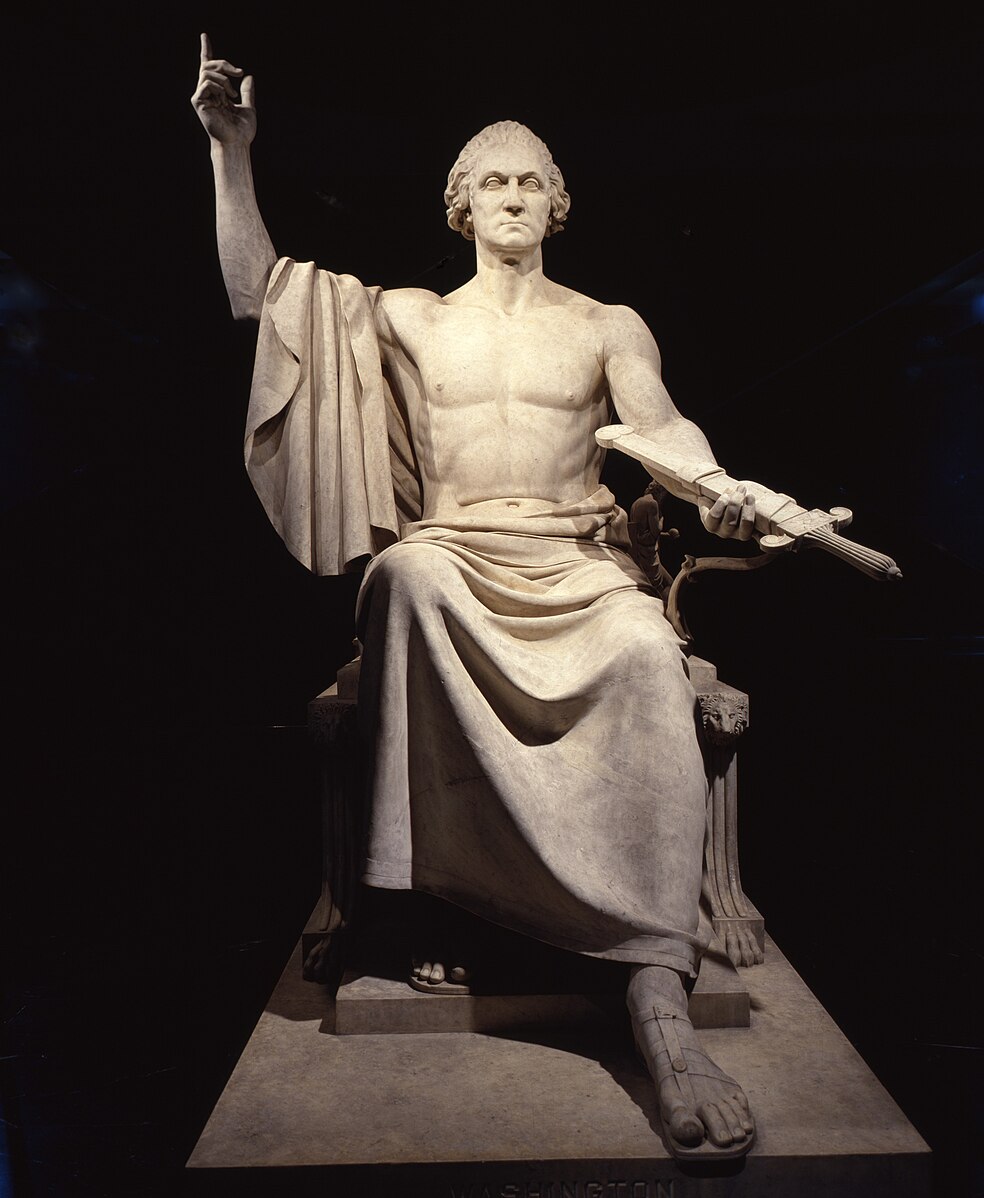

SY: I’ll go with an odd little book from 1916 called Little Journeys with Martin Luther, written by a Lutheran minister in Columbus, Ohio. The work is a strange mix of theological diatribe, translation, and science fiction. The narrator begins his story standing in front of the large Martin Luther statue in Washington, DC (erected in 1884 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Luther’s birth). Gazing at the bronze image of the reformer, the minister is flabbergasted when the statue comes to life! The reformer steps down from his pedestal, greets the minister, and then spends the rest of the book attempting to gain ordination in the patchwork of American Lutheran denominations. Every synod rejects the reformer for one reason or another, leaving Luther excluded from the whole of American Lutheranism. Though primarily a satirical examination of Lutheran church politics, the book is remarkable for its use of contemporary Luther scholarship. The author has drawn every word that Luther speaks in the book from the latest scholarly critical editions of the reformer’s Latin and German writings (an enormous effort contributed primarily by German scholars), so when interviewed by church officials in 1916, Luther’s responses supposedly reflect his own historical words.

More significant for my research, Luther’s musings in Little Journeys range well beyond theological and ecclesiastical issues. In his travels around the country, the reformer gives his opinion on pressing current events and political issues. He comments on World War I, the immorality of monopolies, economic inequality, the plight of farmers, temperance, and alcohol consumption. He even gives support to the nascent eugenics movement. Again, readers of Little Journeys are assured by the author that all of these words come directly from the scholarly compendium of Luther’s works, and can be trusted as genuine. In Luther-reception studies, there’s an assumption that the critical scholarship that began at the end of the nineteenth century kickstarted a process of “demythologizing” the reformer by emphasizing the distance between the sixteenth century and the modern world. Little Journeys counteracts that claim since the author used the fruit of that critical scholarship in order to demonstrate Luther’s immense contemporary relevance on these issues.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

SY:

The founding generation had a wide appreciation of history and a keen understanding of the new nation’s continuity and discontinuity with the past.

SY: The instability of the Revolution and the founding of the Republic led many American leaders to look to previous eras for wisdom and encouragement. Biblical texts, classical authors, and the musings of philosophers, scientists, and theologians filled their libraries and bookshelves, and they cited these works throughout the American Revolution and the debates over the Constitution. As the country expanded and new problems emerged, partisans on all sides attempted to invoke historical events, figures, and movements to aid their cause, including—within a generation of their deaths—the founders themselves! The use, abuse, and politicization of history may be a feature of contemporary public discourse, but it’s important to remember that this is nothing new and has a long tradition in American life.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about American history?

SY: I first came across W. J. Rorabaugh’s Alcoholic Republic as a graduate student, and it completely changed the way I thought about early American history. From 1790–1840, average alcohol consumption in America peaked at 7.1 gallons of distilled liquor per capita, over three times today’s consumption rate. When I share this fact with my students, it helps explain two important developments: first, the pervasiveness of violence in antebellum America. Alcohol fueled the mobs, riots, lynchings, vandalism, and duals that threatened the nation’s growing urban areas and the often lawless frontiers. Second, the appeal of the temperance movement. My students often scoff at the 18th Amendment and the failures of Prohibition, but temperance had broad popular appeal as a social cause precisely because alcohol was a pressing problem in the nineteenth century. Most Americans knew someone whose drinking had led to domestic violence, suicide, or poverty.

ED: Thank you so much for your time and work!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).