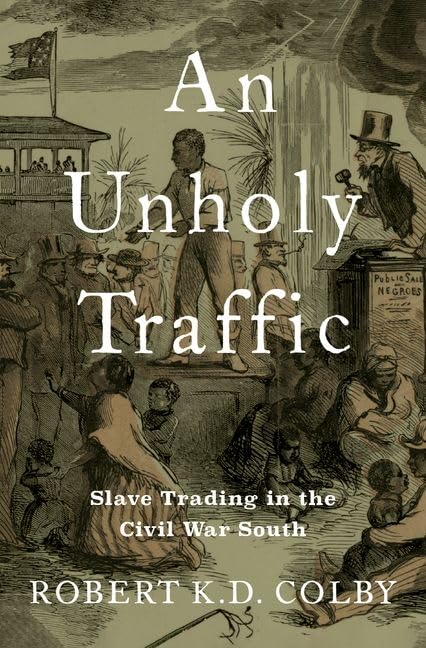

An interview with Robert K.D. Colby

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Robert K.D. Colby to discuss his new book, An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South. Dr. Colby is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Mississippi.

The fundamental understandings of the American republic

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

RC: I sometimes feel as if I could hardly have helped doing so! I grew up in the Washington, D.C. area with parents who were highly engaged in history. We spent a great deal of time at museums and on battlefields, which immersed me in various aspects of American history. As I got older, history appealed to me more and more as an interpretive lens. It seemed clear to me that history was the key to understanding why events happened in the way that they did, and that the roots of the present were deeply sunk in the past. When combined with a series of outstanding instructors in history, this set me on the path toward becoming a historian.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

RC: I am a historian of the American Civil War era. I study that period, particularly through social, cultural, and military lenses. I have a special interest in the Civil War’s effects on slavery and the ways in which the enslaved won their freedom during the conflict. The histories of enslavement and emancipation have interested me for as long as I can remember having been aware of them. I think I always saw them as the fundamental tension in the American history that I had been taught. The seeming contradictions between slavery and American ideals became something I had to understand and explain to my satisfaction. As I did so, once again, I benefited from extraordinary teachers—particularly Gary Gallagher and Michael Holt at the University of Virginia—who underscored to me the centrality of the Civil War era to understanding the United States. I thus became a scholar of both the Civil War and American slavery.

ED: Explain the thesis of your new book, An Unholy Traffic: Slave Trading in the Civil War South.

RC: At one level, the thesis of the book is pretty straightforward: the domestic slave trade—the purchase, sale, and movement of enslaved people within the United States—survived throughout the American Civil War in spite of all the pressures the conflict placed upon it. Why it survived, however, is considerably more complicated.

I argue that the persisting slave trade allowed white Southerners to adapt to the challenges of the conflict, including the demands a near-total war placed upon them and the threat of emancipation.

RC: It also allowed them to invest in the slaveholding society they believed would emerge from the conflict. The slave trade thus proved an incredibly flexible tool that shaped the experiences of all inhabiting the wartime South—those doing the purchasing and selling, and those whom they bought and sold.

ED: You open your book with a gripping story involving slave trader Robert Lumpkin and fifty enslaved people. Who was Robert Lumpkin, and how did his efforts to smuggle fifty enslaved people out of Richmond represent, in your words, “a microcosm of the Civil War”?

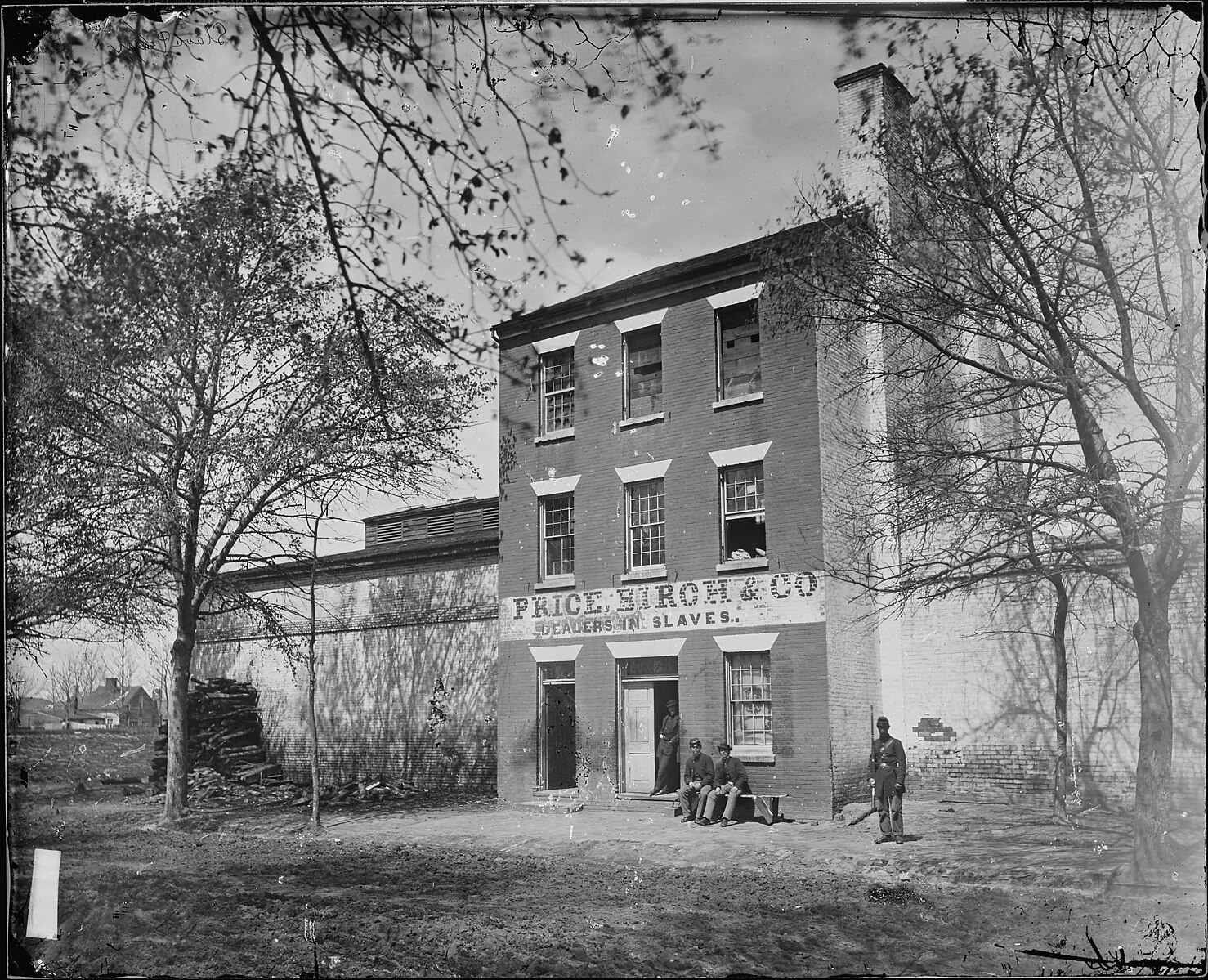

RC: Robert Lumpkin had, for nearly three decades, been a professional slave trader in Richmond, Virginia (currently, I-95 runs right over the site of his jail as it crosses the city). In his younger days, he had bought people in Virginia and driven them personally to the cotton and sugar frontiers of the Old Southwest. By the 1850s, however, he mostly operated a jail (see left for an example of a “slave jail” in Alexandria, Virginia) and trading complex that catered to others’ slave dealing; he lived there with an enslaved woman named Mary (whom he forced into an ongoing sexual relationship) and their children.

When Richmond fell to Union forces, Lumpkin tried to move fifty people out of the city, an effort primarily aimed at preserving them as human property and the value he and other enslavers stored in them. Lumpkin was a creature of a world built on slavery, and the fact that he struggled to extend it even at the bitter end of the Civil War demonstrates the degree to which Confederates fought to maintain a world with slavery at its core.

ED: How did Southern enslavers adapt their trade in enslaved people to the realities and exigencies of the Civil War?

RC: They did so in a number of ways. They shifted the geography of the trade as Union forces pierced ever more deeply into the Confederacy. They also adapted the reasons for which they purchased and sold people. Certainly, transactions in pursuit of economic gain continued as slaveholders speculated in human property (which they believed would grow ever more valuable with Confederate independence achieved). But they also used slave commerce to gird themselves for war and to endure its hardships. Enslavers, for example, sold people whom they felt they could no longer feed, or whom they found too difficult to control as the war disrupted the institution of slavery. They sold people to acquire substitutes to take their place in the military or to outfit themselves for war. They acquired people to address labor shortages as men went off to war, or to fit a specific need the war create

The slave trade was thus a remarkably malleable piece of the Confederate war effort, one that allowed many white Southerners to displace the challenges of war onto the enslaved.

ED: Cities like New Orleans, Louisiana, and Charleston, South Carolina, were crucial hubs of the slave trade before the Civil War. How did commerce in the enslaved function in these particular cities during the war?

RC: These cities in many ways represent the diverging experiences of the Confederacy. Slave commerce in New Orleans basically ended in the war’s second year when Union forces occupied the city. Slavery remained legal there, but US soldiers only irregularly enforced the laws required to turn people into property, without which the trade in slaves could scarcely function. Enslaved property became simply too risky an investment in a world in which a person could flee, and enslavers could not trust those charged with policing enslavement to help return that person to bondage.

Charleston, on the other hand, remained in Confederate hands throughout the war, and despite a regular siege and ferocious bombardment, slave trading continued in the city. Large-scale sales took place throughout the war’s first several years (sometimes involving more than one hundred people at a time) because in Charleston and its hinterlands the Confederate state remained vital and largely preserved and policed the institution of slavery.

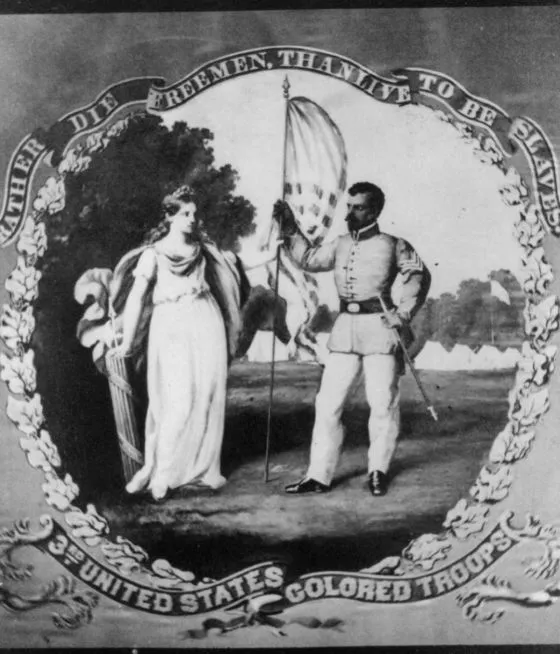

ED: As we all know, Black Americans resisted enslavement and the slave trade before the war. Did the ways in which Black Americans resisted enslavement change during the war, and what effect did their resistance have on the slave trade and overall Confederate war effort?

RC:

The Civil War opened up extraordinary new opportunities for African Americans to resist enslavement, most notably through flight to the refuge offered by Union soldiers and sailors.

RC: And the persistent arrival of fugitives from slavery forced Union officials at all levels to gradually expand the policies governing their treatment of them. The slave trade, however, complicated African Americans’ calculations as they considered availing themselves of this option. Confederates regularly sold people whom they suspected might flee (though, in doing so, they often sparked the flight of others who, in turn, feared being sold), and waves of sales preceded the Union army’s arrival in any region it approached. Fugitives who failed to reach Union lines, or whom Confederates recaptured after their arrival—including when armies occupied or vacated areas—also frequently underwent sale south. Jittery enslavers also sold enslaved people for an ever-escalating number of infractions against the slaveholding order as they felt the war threatening it. The slave trade, African American resistance, and emancipation were thus all bound up together during the war.

ED: The names of the slave traders you study have all but disappeared in our national memory. Why have historians forgotten about these men? And what happened to these slave traders once the war ended?

RC: Very few slave traders were well known in their own time—though the idea that they were universally disdained, even by slaveholders, is a myth constructed in the antebellum period to defend slavery more broadly. Wealth shielded some slave traders from criticism; more often, however, they faded into obscurity after the Civil War. Several of the most notorious also died during the war (including one who blew himself up on a landmine while working for the Confederate government). Many of their former facilities either fell into disuse, were repurposed, or were destroyed after the Civil War. Thus, unlike other aspects of the conflict, relatively few physical markers of the slave trade survived to inject the memory of the trade into recollections of the conflict. The slave trade had also been a particularly contentious part of the ideological struggle over slavery before the Civil War, and much of the early literature on the American South either ignored it or diminished its importance as an extension of that battle. This continued into the late 20th century; it was only in the 1980s that historians began to reconsider slavery primarily through the lens of the slave trade.

ED: Tell us about some of the sources you consulted throughout the course of your research.

RC: One of the reasons the wartime slave trade has been overlooked for so long is the fragmented nature of the sources depicting it. On the one hand, the wartime slave trade was everywhere. I found references to it in hundreds of collections of wartime letters and diaries, innumerable published materials, and all over contemporary periodicals and government records. On the other hand, it is the specific focus of relatively few of these collections. My project was thus largely one of matching single lines in letters written by Civil War soldiers with individual diary entries, newspaper articles, and military and court documents. Collectively, these form a mosaic that provides a coherent picture of a surviving commerce in enslaved people that endured to the last days of the Civil War.

A cordon of liberty

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

RC: At the heart of a study of the wartime slave trade lie questions of freedom and fundamental understandings of the American republic. As Andy Lang has shown, the Civil War emerged in large part over clashing visions of American democracy, and, given the lengths to which they went to perpetuate it and the persistence with which they engaged in it, the survival of the wartime slave trade underscores the salience of slavery in the Confederacy’s vision of American life. It also speaks to the potency of Constitutional interpretation and application. As James Oakes and others have argued, a vibrant anti-slavery strain of Constitutional thought emerged in the decades leading up to the Civil War. While this had its limits, the eradication of the slave trade in Union-occupied areas show the power of these ideals put into action—the application of the “cordon of liberty” was a very real phenomenon.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about the American political tradition?

RC: For me, the most profoundly impactful part of this project involved tracing African Americans’ bids for freedom during the Civil War. That they pursued them even at the potential cost of sale and separation from friends and loved ones speaks to the power of the ideals of liberty and the promise of the American experiment. The challenges against which they struggled and the costs they incurred to attain even an incomplete version of that freedom are a potent reminder of the value of something we too often take for granted.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).