An interview with Robert Allison

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Robert Allison to discuss his work on the American Revolution, Olaudah Equiano, and the fundamental premise of 1776. Dr. Allison is a Professor of History at Suffolk University in Boston, and also teaches in the Harvard Extension School.

The fundamental premise of 1776

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

RA: I do not remember a time when history did not interest me, but the idea of being able to read, write, and teach history as a vocation did not occur to me until I was in my late 20s. I had begun my college education as a history major in the mid-1970s, and there were few jobs for historians. What would I do with a degree in history? I asked that, and so did just about every person who found out what I was studying.

So I dropped out of college and became a cook.

I was still reading a lot of history, though, and during a couple of years as a cook in Phoenix, I started taking classes at Arizona State and also haunting the used bookstores and the Phoenix Public Library (which had great book sales). At one of these sales I picked up books that I still have in my office—Henry Adams’ History of the United States in the Administrations of Jefferson and Adams, a collection of Great Slave Narratives, edited by the novelist and Arna Bontemps, which included The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano, and Bernard Bailyn’s Ideological Origins of the American Revolution.

I did not think the Phoenix Library had enough books to be getting rid of these, but it was my gain. All of these books gave me a turn of thinking, and I decided to finish college. Happily, a friend who worked at the same hotel was moving to the Boston area, and even more happily I saw an interesting statistic, in Phoenix for every 100 women, there were 120 men, while in Boston the ratio was reversed. I came to Boston, found a job in a restaurant where I met the woman to whom I have been married now for 39 years and also started taking classes at the Harvard Extension School. There I met some terrific professors, in history where Drew McCoy taught the early American Republic and Colonial America (two courses I have since taught there), and Werner Sollors taught African-American literature.

Sollors and McCoy encouraged me to think about graduate school, so I did and wound up in the History of American Civilization program at Harvard, and in my first semester, I took Bernard Bailyn’s seminar. I still think about the questions he asked in the seminar. More importantly, he hired me to be his research assistant on a project he was doing on the ratification of the Constitution, where my job was to look up things he did not know off the top of his head. Those things were quite obscure. This was the best learning experience in my career as a historian, though I did not realize it at the time.

Graduate school on the whole was fun—something of a luxury to spend my time reading, writing, or teaching, after having spent my working days or nights flipping eggs in the morning or steaks and burgers at night (I continued working summers in a restaurant on Cape Cod).

RA: By this time there were fewer jobs in history than when I started off twenty years earlier. My wife and our now two sons were rooted in Boston and did not want to move. Sollors suggested sending my c.v. to every college in the greater Boston area, telling them what I could teach. I mailed out 60 copies of my c.v., and got back 59 letters saying thank you, this looks interesting, but we are all set. But, the chair of Suffolk’s history department called and said they had a faculty member going on leave that fall, and he needed someone to teach Colonial America and the Civil War. So I was hired and enjoyed the students and my colleagues so much that we thought of ways to keep me at Suffolk, and I have now been here since 1992. The following Spring, after I earned my Ph.D., I began teaching at the Harvard Extension School.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

RA: The American Revolution, the Colonial period, and the formation of the U.S. Constitution are my areas of specialization. I continue to learn new things about all of them.

It might have been visiting Washington’s headquarters in Morristown, or reading Robert Lawson’s Ben and Me, but then there were a lot of interests I had as a kid that I cannot recall. The American Revolution remains fascinating because, unlike every revolution in my lifetime, and most of those that I know about, the American Revolution did not replace one oppressive regime with another. What we learn from studying revolutions is that overthrowing the bad old regime, though it seems impossible, is actually easier than creating a new regime that is not worse. We should be able to learn something from this

ED: Can you share a historical incident that happened in Boston that would surprise Americans?

RA: In 1920 a man named Charles Ponzi opened an investment office on School Street. So many people came to invest with Mr. Ponzi’s Securities Exchange Company that the City allowed him to park on the street—next to City Hall, the only other person allowed to park there was the Mayor. People came because Ponzi could double their money in 90 days. If you do not understand how this investment scheme works, contact me directly as I have a great opportunity for you.

Ponzi did not invent the pyramid scheme, but it gets its name from his brief career on School Street.

Faith and work

ED: Tell us a little bit about Olaudah Equiano’s character. Which of his character traits should students strive to emulate?

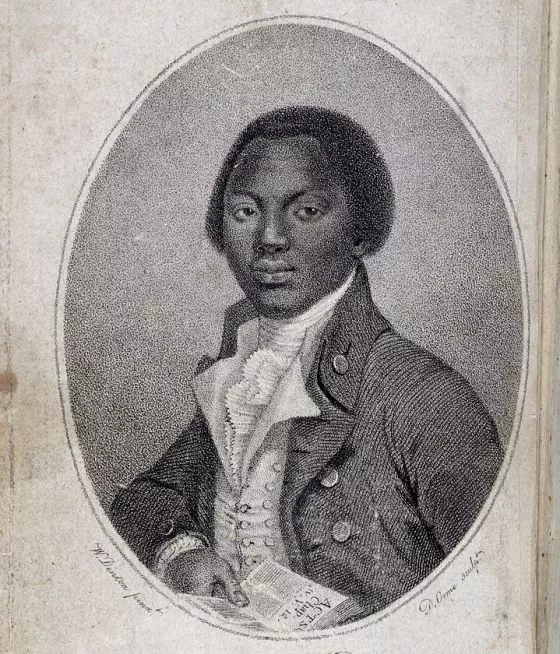

RA: Equiano (left) worked hard and had faith. He questioned those around him, as well as himself. His story is astonishing, and though the Interesting Narrative is categorized as a “slave narrative,” for most of his life he was free, and the ten years he was enslaved is only a small part of the life he outlines in the book. His life as a free man, traveling from the Caribbean, to England, North America, the Arctic, and the Mediterranean tells us much about the world as he knew it.

ED: What was your favorite primary source that you uncovered during your research?

RA: The last piece Benjamin Franklin wrote that he saw in print, in March 1790, was a satire aimed at a pro-slavery argument Congressman James Jackson made on the floor of the House. Franklin’s name had been attached to a petition asking Congress to end the slave trade, and Jackson responded with an argument that slavery was actually beneficial to the enslaved. Franklin took Jackson’s argument and rewrote it as the speech of a fictional Algerian justifying the enslavement of Christians in the 1680s. After hearing the pro-slavery argument, Franklin concludes, that the rulers of Algiers agreed that ending the practice of enslaving Christians would be “problematic.” He feared with justification a similar result in Congress.

ED: Are there any misconceptions about American history that you’ve enjoyed debunking?

RA: One misconception is that the generation who based their Revolution on the principle that “all men are created equal” did not actually believe that. Certainly they not only tolerated, but in some cases benefitted from, the marked inequality among people. And by the 19th century, equality as a starting point was no longer a self-evident truth.

But this change was a historical development.

The fundamental premise of 1776 was that all men were created equal, each endowed with fundamental rights. How to reconcile this fundamental premise with the institution of slavery was their great conundrum, but they did not dispute the inherent rights of all people, violate this principle as they might.

RA: A subsequent generation found this inherent contradiction too difficult, and had to choose between their forebear’s principle of equality and their own interest in slavery. For the most part, they chose to keep slavery. Fortunately enough of their countrymen held onto the principle of equality—David Walker, Maria Stewart, Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln—to allow us to reclaim this fundamental principle after a bloody war.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

RA: The founding generation included some extraordinary men and women, who would have been leaders in any society, and whose ideas can still challenge and inspire us. But they had disagreements among themselves—profound and serious disagreements—and their time also included its share of con artists, dilettantes, and reprobates. The fundamental principles that shape the Massachusetts Constitution, which John Adams wrote in 1780, and the U.S. Constitution that we credit Madison with framing—power checking power, ambition checking ambition, to the end, as the Massachusetts Constitution says, “that this will be a government of laws, and not of men,” were not designed because this generation was better than we are, but because this generation understood human nature. “If men were angels,” Madison wrote, “no government would be necessary.” And, as Madison noted, “If every Athenian were a Socrates, the Athenian assembly still would have been a mob.”

A few weeks ago I was talking about the creation of the U.S. Constitution with a colleague from France. He was struck by the fact that since 1789 the United States has had one government, while France has had eleven—five Republics, two Empires, two monarchies, and the Vichy regime and DeGaulle’s provisional republic.

Our Revolutionary generation got something right, creating a system that continues to work, has allowed the country for which it was created to grow and prosper, and allows us to continue arguing with one another without cutting each other’s throats.

ED: What is one thing you wish everyone knew about American history?

RA: American history is fascinating, filled with extraordinary stories—not just stories that will inspire or admonish, but will entertain and enlighten. It is always interesting, as we consider the different problems people have faced over the centuries of our national existence, and the various solutions they have imagined for their problems and challenges. Sometimes the solutions worked, often they did not. We can learn much from successes and failures.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).