An interview with Rita Koganzon

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Academic Council Member Rita Koganzon. Dr. Koganzon teaches at the University of Houston. In addition, she won the Jack Miller Center’s 2021 Excellence in Civic Education Award.

ED: Why did you become a political scientist?

RK: By accident. I intended to be a historian, and I majored in history as an undergraduate. When I was applying to graduate programs however, I wanted to write a dissertation on Locke’s and Rousseau’s educational treatises, both of them together. But the professors I was interested in working with discouraged such a broad topic – two different countries in two different centuries! I never took a political science course in college, but I had taken some courses in the Fundamentals: Issues and Texts program at the University of Chicago, a kind of great books program, and those were often cross-listed with political theory. And I had several friends with similar interests in the history of political thought who’d gone on to graduate programs in political science, so I applied to some as well. Conveniently, no one in these programs thought my proposed topic was too broad. And it did become my actual dissertation, so it was a good choice in the end.

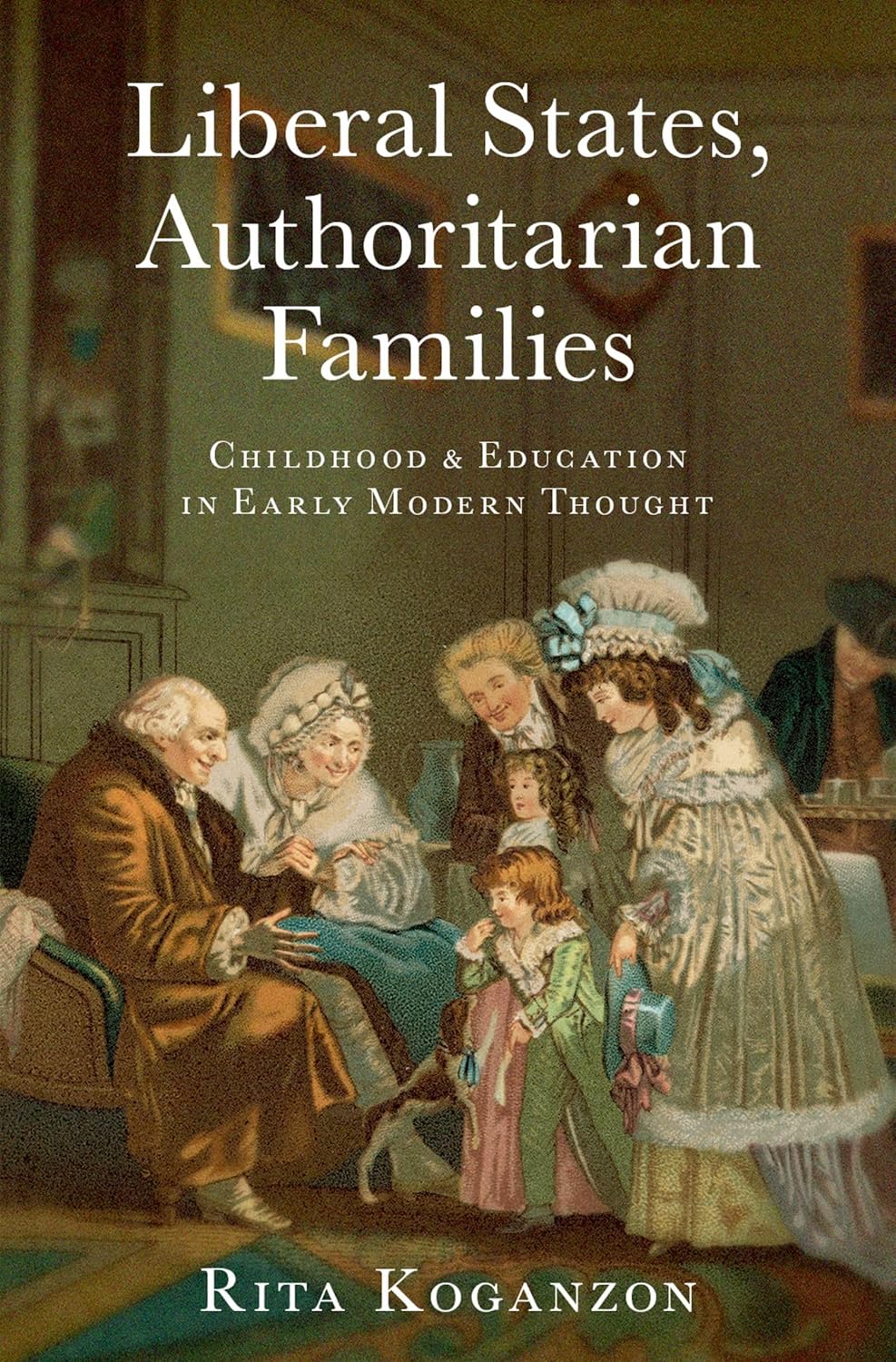

ED: What inspired you to write Liberal States, Authoritarian Families: Childhood & Education in Early Modern Thought, and what types of questions guided your research?

I wrote my book out of a personal interest in the problem of exercising authority over children in a liberal democracy. I always resented having it exercised over me in school, so I was, for an otherwise serious student, frequently in trouble. Most of my teachers seemed totally inept, and I didn’t see why they should wield any kind of power over me, so I invested a lot of effort in mostly absurd ploys to undermine them. But in college, I totally lost this impulse. I encountered for the first time a critical mass of teachers who seemed naturally authoritative – they were erudite and impressive and I wanted to be like them instead of to humiliate them.

My dissertation, which became my book, was an effort to understand this seeming contradiction in liberalism – on one hand, children are mostly fools like me, and need authority to reach adulthood successfully. But on the other, there are few resources in our political theory, which is grounded in equality and liberty, to justify such authority. So I looked to early modern educational theorists like Locke and Rousseau to see how they dealt with this problem in their arguments for new approaches to education suited to this new regime.

ED: In Renewing America’s Civic Compact, you write about the tension between meritocracy, democracy, and higher education. What is the nature of this tension, and to what extent can we alleviate it?

RK: One major challenge to education in democracy is that our desire for equality is permanently in tension with our desire for excellence. Education beyond a very basic minimum is always an engine of distinction and hierarchy, never one of equality (since we are most equal when no one has any education), and we find this very difficult to accept. Some version of meritocracy has long been the American resolution to this tension – from Jefferson to Tocqueville to DuBois to James Conant. Meritocracy worked best in the US when its institutions and paths to success were decentralized across the country, but as a mechanism of selection, it is always susceptible to centralization – finishing high school somewhere no longer suffices when a college degree becomes commonplace, and just any college degree is no longer good enough when everyone gets one so you need the best one, and so on – which ends up hardening hierarchies in anti-democratic ways. We are always in this bind, and it’s difficult to consciously and systematically decentralize meritocratic opportunity, so our best bet lies in preventing over-centralization in the first place.

ED: Your article on book banning from the American Political Thought journal analyzes the rise of children’s “right to read.” How does this right to read impact our public education system?

RK: In the article, I argue that the “right to read” (like most students’ rights, as it happens) is a mirage and a strategic invention by educators who wanted to evade parental and community oversight for their curricular choices – in this case, the books they selected for school curricula and school libraries. Appeals to the “right to read” have made our subsequent book removal and censorship debates impossible to resolve because they allow one side – mostly the side that wants to shelve controversial books that parents and boards disapprove of – to hide behind “student rights” instead of making the positive case for their selections and being accountable to the ordinary governance structure of schools for them.

These ordinary forms of democratic school governance – oversight by elected boards – have come to be maligned as censorship and “book banning,” which only empowers unelected and unrepresentative educators to govern local schools.

A debate of two figured

ED: If you were able to moderate a debate between two thinkers across time and space, who would you choose and why? RK: Alexis de Tocqueville and Woodrow Wilson. They both make compelling arguments for seemingly completely opposed views of the role of central government. Is their disagreement a matter of permanent principle, as it’s often read, or of a contingent response to the political and economic conditions that prevailed around them?

ED: What is your next project?

RK: My next project is a book called Hating School, about the history of opposition to schooling in American educational thought, and the salutary role it’s played in our political tradition.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about the American political tradition?

RK: I wish people knew a lot more about it overall, but the one narrow complaint I had for a long time was ignorance of the virtues of American federalism, and of decentralization of government and society more broadly. My undergrads often seemed like Adam Smith’s “men of system,” overly attracted to the aesthetic pleasure of observing an orderly and uniform whole, and unable to tolerate the ugly messiness of a variety of state and local laws and practices. This was more true in Virginia, a state so intimately connected to Washington D.C., than here in Texas, whose location and geography and history make centralization less intuitive. And as control of the courts has shifted right and the executive has become more of a toss-up, I think many of the students who used to see central government as a savior have themselves become more skeptical of it. So there is hope!

ED: Thank you for your time and insights!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).