An interview with Rachel Ferguson and Marcus Witcher

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholars Rachel S. Ferguson and Marcus M. Witcher to interview them about their latest book, Black Liberation Through the Marketplace: Hope, Heartbreak, and the Promise of America. Dr. Ferguson teaches at Concordia University Chicago, and Dr. Witcher teaches at West Virginia University.

Commentating the American Dream

ED: What inspired you two to become scholars? What are your areas of specialty, and what sparked your interest in those topics?

RFMW: Rachel is a philosopher focused on political and economic philosophy, and property rights in particular. Marcus is a 20th century political historian. He studied with the civil rights historian David Beito who sparked a passion for minority rights from an individualist perspective. As long-time members of the liberty movement, both Rachel and Marcus knew that classical liberal scholarship on race and discrimination was both deep and profound. Just think of Gary Becker’s work, for instance. But with the events in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014 and the rise of Black Lives Matter, it became immediately apparent that classical liberal insights on racial discrimination were not well-known or understood. Someone needed to put these insights, both philosophical and historical, into one place!

ED: Explain the thesis of your new book, Black Liberation Through the Marketplace: Hope, Heartbreak, and the Promise of America.

RFMW: In Black Liberation Through the Marketplace, we argue against the false dichotomy between being pro-Black and big government and being small government but cavalier about the oppression that Black Americans suffered. Instead, we demonstrate that classical liberals throughout history stood stalwartly against slavery, fought for full Black legal rights, and defended the dignity and independence of Black Americans.

Furthermore, classical liberalism offers profound insights into the nature that Black oppression took. This includes exclusion from the equal protection of the rule of law in cases like convict leasing, lynching, and massacres; exclusion from the defense of their property rights, not only during slavery but also after emancipation when courts would not defend their claims to land and goods; and of course, their freedom of contract, as we see clearly in the case of the whole program of Jim Crow, which forbade free trade and even marriage between Black and white Americans, but also in the shocking eugenicist push for minimum wages and other wage and hour laws to disemploy ‘undesirables.’ Conversely, civil society institutions such as the Black Church, the National Negro Business League, and a wide array of fraternal associations built up a middle and upper income Black leaders that led the incredibly successful and ethically sophisticated Civil Rights Movement. Looking toward the future, we maintain a small government, pro-Black position in pursuit of economic freedom, educational freedom, criminal justice reform, and healthy forms of charity.

ED: Your book contrasts the deep historical injustices experienced by African Americans with the success of African American entrepreneurs. How did you achieve that balance?

RFMW: From the earliest stages of the project, we knew we didn’t want to only focus on the negative aspects of Black history or on the struggle for civil rights. Black Americans’ experience is so much richer and more complex than that.

The story we wanted to tell was a story of a people who overcame incredible challenges–many of which were imposed on them by the state.

RFMW: We wanted to avoid the conservative tendency to white wash the past by not discussing the very real atrocities committed against Black Americans but we also wanted to avoid the progressive inclination to only focus on oppression. In sharp contrast, we dedicated ourselves to telling the whole truth–or at least as much of it as we could in the space that we had. And we are really pleased with the result. Detailing the hardships that Black Americans endured helps to impart how impressive the achievements of Madam C.J. Walker, John H. Johnson, T.R.M. Howard and others were.

ED: You employ the term “classical liberalism” throughout your book. How would you explain “classical liberalism” to a non-academic?

RFMW: We kept things simple by focusing on five aspects: the three fundamental legal institutions of private property, freedom of contract, and the equal protection of the rule of just laws, as well as the cultural commitment to free markets and to thick civil society institutions. The three legal institutions provide the framework within which human dignity can be respected and expressed through all sorts of creative, cooperative endeavors. If we’re not going to be ruled by others, however, then we must rule ourselves! That’s where healthy markets and deep social ties must be cultivated through the efforts of virtuous citizens.

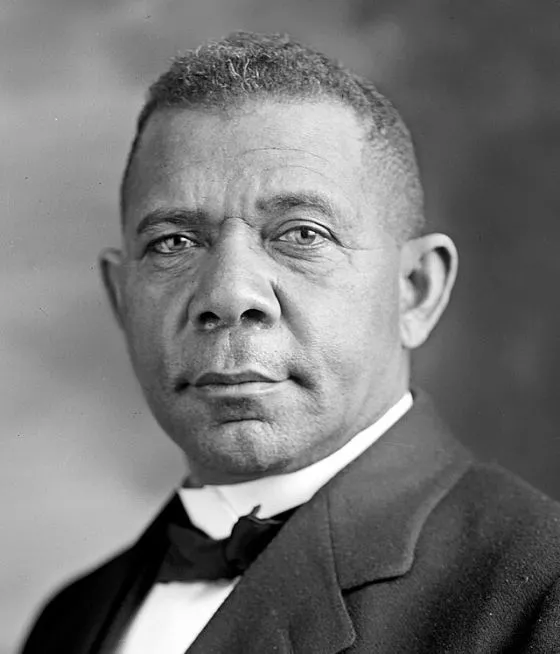

Washington was a keen student of Frederick Douglass

ED: Keeping with “classical liberalism,” give us a few examples of African Americans who utilized classical liberalism to further the Civil Rights movement.

RFMW: Frederick Douglass is of course the most obvious answer to this question. He was undoubtedly a classical liberal and he fought relentlessly for the end of slavery. After the Civil War, Douglass dedicated himself to advocating for Black Americans’ political and civil equality. A big advocate for limited government, free trade, and market capitalism, it is the tragedy of his life that he witnessed what some labeled the “re-enslavement” of Black Americans during the 1870s and beyond.

Booker T. Washington inherited Douglass’ mantle following the former’s death in 1895. Washington believed in self-help, education, and the power of voluntary associations. In addition to building the Tuskegee Institute from the ground up, he organized civil society organizations such as the National Negro Business League to help Black entrepreneurs come together to pool resources, bounce ideas off one another, and mobilize for the betterment of the race. Rarely discussed, Washington was also involved in securing presidential appointments to key judicial postings (including one that addressed a huge swath of the convict leasing practice) and in trying to enact change behind the scenes (often through financing lawsuits against injustice prior to the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People).

RFMW: A final example of a Black classical liberal who fought for civil rights was T.R.M. Howard. A physician by training, Howard moved to Mound Bayou, Mississippi and helped mobilize black Americans during the 1950s. Famously well-armed, he supported and protected Emmett Till’s mother while an all-white jury ultimately determined that Till’s murderers were not guilty. Following this injustice, Howard revitalized an old idea that Black Americans should mobilize a March on Washington. He traveled the country speaking to community groups and church congregations.

At one of his stops, Dr. King’s Dexter Avenue Church in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks was in attendance. She later said that Howard’s words helped convince her to take her stand and not give up her seat on December 1, 1955.

ED: To what extent is your book a commentary on the “American Dream”?

The book outlines the quintessential story of the American Dream.

RFMW: While European settlers fought for their own freedom, enslaved Black Americans learned to fight for theirs as well. They dreamed of enjoying the full rights of citizenship and sharing in the prosperity that a free society makes possible. But while so many obstacles were thrown in their way, some amazing entrepreneurs and cultural innovators broke through their barriers. They lifted up not only themselves, but their fellows as well, through the web of exchange within the Black community referred to as ‘Black self-help.’ Just consider that between emancipation and 1930, Black literacy rose from 8% to 80%! An amazing feat. One of the saddest parts of the story is the way that massive, progressive, federal intervention in the 1960s and 1970s tore apart what had been so meticulously built over the course of the century. FHA redlining, the Federal Highway System, perverse incentives of the welfare state, and so-called Urban Renewal scattered the communities with strong marriages and high employment rates. They were already seeing plummeting poverty rates: between 1948 and 1966 the Black poverty rate was cut in half! But much of that wonderful momentum was slowed nearly to a halt by these terrible policies. We are still paying the price today in our most destabilized communities.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

RFMW: This research has reinforced our belief in the founding principles of our nation. While many condemn the founding generation, their dedication to Enlightenment liberalism set the stage for the abolitionist movement and the civil rights movement. Almost all the Founders believed that slavery was a perverse system of labor and that it violated their belief in individual liberty.

They believed that the institution would die of natural causes in the early 19th century. That didn’t happen for a variety of reasons including the invention of the cotton gin. But their insistence that individuals have certain rights that are endowed upon them by their creator provided future generations of patriots to use that rhetoric to claim the moral and intellectual high ground.

Their eloquent belief in the rights of individuals has continued to inspire revolutionaries and movements all across the globe who fight for liberty in the face of government oppression.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

RFMW: The United States of America represents the first great experiment in liberalism: a society based not on nobility of birth but on merit, and formed with the confidence that a free people can do amazing things. But it was saddled with a completely contradictory institution: slavery. It would be far too simple to say that the central concept of America is slavery, as some (such as the NYT 1619 Project) have claimed, but the key role of slavery and racial oppression in our history is absolutely undeniable. Nevertheless, a large swath of the American Founders were themselves anti-slavery, or at the very least, knew that slavery had to be eliminated if the republic was going to survive.

The strange thing is that the racialization of slavery actually intensified due to the abolitionist pushback on the institution, creating a bizarre dynamic in which legal institutions were improving while cultural racism was actually progressively getting worse. Understanding these nuances is so vital: students need to know that our history of racial discrimination is an abrogation of our liberal principles, and consistently required government intervention to maintain! Instead of giving up on the American project because of this element of our history, we should rather affirm the ways in which we (eventually) held ourselves accountable for our hypocrisy and fight hard for a prosperous future together as one nation.

ED: Thank you for your time and insights!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).