An interview with Professor William Inboden

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Academic Council member William Inboden to discuss his work on President Ronald Reagan as well as the uniqueness of the United States and its history. Dr. Inboden is Professor and Director of the Hamilton Center for Classical and Civic Education at the University of Florida

Founded on an idea

ED: Thanks for agreeing to this interview! Why did you become an American historian?

WI: It goes back to my childhood. I always loved reading history books. I mean, even as a kind of nerdy six or seven year old, my mom would take me to the library regularly and I always wanted to check out history books, usually military history. It’s something that always stayed with me. I majored in history as an undergrad and then earned a PhD in it.

Why this love of history? I think it’s because it brings to the fore the human element and human story in major events. The reason why I always kept coming back to history, rather than say political science or related fields, is because history really puts human contingency, agency, and leadership a little more at the forefront of shaping events. It’s absolutely fascinating to study those in the past and it’s an endlessly rich vein of unknown, undiscovered, and unappreciated stories.

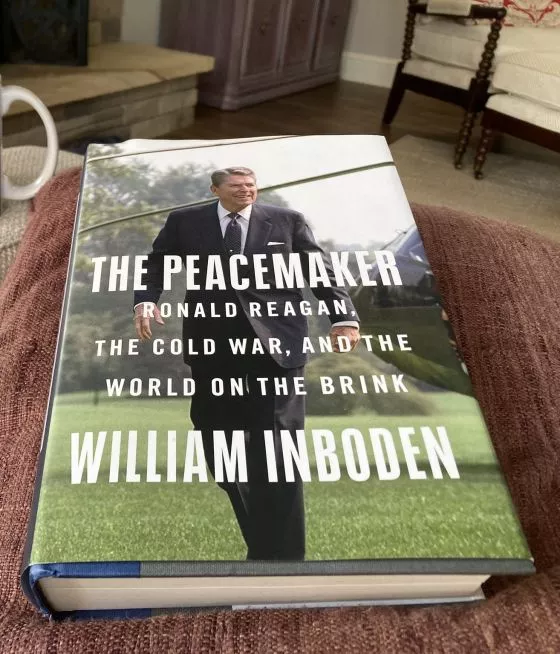

ED: What led you to write your book on President Ronald Reagan?

WI: A number of different strains came together. Some of it is in my own personal odyssey growing up during most of the years of the Reagan presidency. He had been something of an enigmatic figure of fascination. During the fall of my senior year of high school in 1989, the Berlin Wall came down, and my sophomore year of college was when the Soviet Union collapsed. Those were formative experiences for me as a young person, but I never really studied them in depth as a scholar.

A few decades go by, and I’m trying to decide on my next book project. Even though a lot has been written on the Reagan presidency and the peaceful end of the Cold War, I hadn’t yet seen what I thought was a satisfying synthetic treatment of all the different foreign policies that Reagan was trying to navigate and manage during a pivotal decade. Having worked at the White House and with the National Security Council for President George W. Bush, I had more of a firsthand appreciation of how national security is done during the presidency, including the stresses the pressures, conflicts, and difficult decisions made with uncertain information.

I’m fascinated by this question of presidential leadership: can presidents really make a difference in history? Or is history just these impersonal forces and tectonic plates and ineluctable tides? I don’t think so. I think history really is shaped by individual people, especially consequential world leaders. Reagan seems to stand out as an especially consequential one who had a very particular, unique, and insightful set of ideas about the nature of the Cold War.

He challenged the conventional wisdom that denied that a peaceful American victory was possible, and then set about to make that happen.

ED: Why do we need to read your book?

WI: There’s a growing sense of how far removed we are from the peaceful end of the Cold War. A lot of Americans and other people around the world believe the collapse of the Soviet Union and a peaceful end of the Cold War was inevitable, that it was foreordained. In addition, they believe that there’s no conceivable way the world would have actually been destroyed in a nuclear war, and that Reagan got lucky, i.e., he happened to be president when all these other things were happening inevitably. I hope people read my book and see an argument against that inevitability thesis.

I wrote my book as a narrative history in part so people can see it unfold chronologically and appreciate that. Very few people at the time in the 1980s thought that the Cold War was going to end, that Germany would be reunified, or that the world would be spared a nuclear war. What I try to do is show how history looked and felt to Reagan and his team as it was unfolding. Every day, Reagan would go into the Oval Office quite literally not knowing if this was going to be his last day alive on planet Earth – but he also knew that the fate of the world rested on decisions he was going to make. He held what was a very controversial belief at the time, that is, that the Soviet Union was vulnerable, could be brought down and moreover, could be brought down peacefully. Reagan came up with a new strategy to advance and implement those beliefs, and I think it ended up being quite successful.

My book is also a case study of one of the last unequivocally successful presidencies that we’ve had, especially on foreign policy. Every president since Reagan has certainly had failings and deficiencies on foreign policy. American foreign policy hasn’t had a great run the last few decades, but this book is a case study of a really successful grand strategy in foreign policy, and the key role of the presidency and making that happen.

ED: What do Reagan’s thoughts and actions reveal about America’s founding principles and history?

WI: That’s a great question because it is key to understanding Reagan himself. He is not an intellectual or history professor, and he doesn’t pretend to be one – but he was much better read than people appreciate and was very much a man of ideas. He viewed the Cold War as primarily a battle of ideas, and he was very strongly shaped by the American founding.

Reagan read much more extensively on the Founding Fathers than was fully appreciated at the time. For Reagan, the United States at its core is a collection of ideas from the founding about human dignity, natural rights, limited government, the virtues of self-government, and a market economy. These are all distinctive to the American founding, but he also sees them as the world’s universal principles; he doesn’t think that these ideas only need to be confined to the United States.

Did you know?

To Reagan, the Cold War was a battle of ideas and part of his strategy was to delegitimize Soviet communism as a viable idea because of its state mandated atheism, totalitarian political control, and command economy. Yet he also wanted to affirm much more positively the virtues of the free world, including the virtues of a free society, which he saw as most perfectly embodied in the American founding. That’s a less appreciated aspect of his strategy.

Most people know that he liked to criticize communism, e.g., he called the Soviet Union “the evil empire” and said they were going to end up on “the ash heap of history.” Yes, he said all that, but he also spent a lot more time than people generally appreciated putting forward a positive vision of the virtues of the free world, with the United States at the center of it. And for Reagan, a lot of that virtue derived from the genius of the American founding.

ED: What is your next project?

WI: Well, here’s where I hope there are some PhD students reading this interview. My book is a synthetic overview of Reagan’s foreign policies and I just did not have the space to go really in depth on a lot of particular ones, and so I came up with ideas for a bunch of new dissertations, maybe even a future book project or two for me. There’s certainly more work that needs to be done on the US-Japan relationship under Reagan – very complicated, very important: he called US-Japan relations the most important bilateral relationship with the world.

There’s also a lot more work to be done on Reagan’s counterterrorism policy. We think of terrorism as part of the 9/11 era, but really, the first big spate of global terrorism was in the 1970s and 1980s. Terrorism was a big challenge for Reagan that he never fully solved. US-Libya relations is another complicated and understudied topic, especially considering that Reagan launched military actions against Libya a couple times during the 1980s.

I write a bit about Reagan’s defense modernization, though there are multiple dissertations or books to be written on that. My teaser for any of our readers on how to think about the fall of the Soviet Union: Reagan didn’t just try to outspend the Soviets militarily. He tried to outsmart them by leveraging America’s technological ingenuity and innovation to design the next generation of weapons systems that were qualitatively better than what the Soviets had.

That was part of the economic pressure on them, i.e., he wasn’t just throwing more money at the issue. There’s a lot more to be studied there.

Then there are individual personalities from the Reagan administration. We need another biography of Bill Casey, the CIA director; we need a biography of Jean Kirkpatrick, his UN ambassador. I feel like my book, as an overview, is just scratching the surface of so much more work that needs to be done on one of the most consequential presidencies and one of the most consequential decades of the last century.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about American history?

WI: I would say something about appreciating the uniqueness of the United States as a country unlike any other that has ever come before. I have a lecture I give my undergrads sometimes on different meanings or different ways of understanding American exceptionalism. One of them, is appreciating how just unique and different the United States is as a country founded on an idea rather than an ethnicity; a country founded on the principles of federalism. Something like this has just not happened before in human history. The one thing that I appreciate is just how unique and different the United States is, and from there flows so many other ramifications and deeper areas to study.

ED: Thank you! We look forward to reading more of your great work!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).