An interview with Professor Thomas Powers

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Thomas Powers to discuss his latest book, American Multiculturalism and the Anti-Discrimination Regime: The Challenge to Liberal Pluralism. Dr. Powers is the Political Science Department Chair at Carthage College.

ED: Why did you become a political scientist?

TP: Politics raises all the fundamental questions of human life. Above all, politics is a crucial site of moral contestation and, as result, politics shapes the human mind (as Aristotle puts it, politics is “architectonic”). In modernity, politics became bound up with “ideas” and thus “intellectual history”—through the Enlightenment and then through the rise of modern “ideologies.”

In the process, the role of ideas sometimes came to seem to be more important than any simple political dynamic. But the civil rights revolution is not rooted in ideas; it is a straightforward political project in which ideas are (once again) the product of the regime. Today the “ideas” that matter are ones that originate in very simple political concerns (contra many who point to “postmodernism” or, more recently, to “cultural Marxism”). Civil rights teaches us, whether we (liberal democrats) want to see it or not, the power of politics to shape human life.

ED: What led you to write your book?

TP: When I first started working on these questions, I was writing a dissertation on “multiculturalism” at a Canadian university (the University of Toronto). Unlike the United States, Canada has an official multiculturalism policy, but the idea of multiculturalism had a certain role in the U.S. as well (this was in the mid-1990s). I suspected that, somehow, “cultural relativism” and related ideas (postmodernism, e.g.) were at the core of the idea of multiculturalism. Wanting to get a job back in the U.S., I looked into “American multiculturalism” but I quickly learned that that meant studying multicultural education (the only important source of the idea in America).

What I saw there was at first hard to understand because the American multicultural education writers of the 1970s and 1980s were not preoccupied with relativism or postmodernism (by the end of the 1990s, it’s true, a merger with postmodernism did occur). Instead, at the outset they were all about “civil rights” and in a very simple and clear way. Once I started to take them at their word, I had to contend with the fact that what they offered was a new civic education for America rooted in the commitments of the American civil rights revolution.

Then multiculturalism came to mean something very different for me—and the project took on much greater importance in my mind. Multicultural education’s teachings were simultaneously familiar, because rooted in civil rights aspirations, but also deeply radical, especially from the point of view of the liberal democratic political tradition. Like everyone else I knew, I had begun by taking for granted the necessity of the civil rights revolution. But here was a whole academic literature compelling me to start to think about the general meaning and implications of that revolution in a way that had not occurred to me.

ED: Why do we need to read your book?

TP: My book tries to take a very broad view of the civil rights revolution and to make use of multicultural education as a kind of guide to that revolution’s aspirations and logic. One can approach civil rights by looking at anti-discrimination law—and my book begins with chapters that do that—but the story of the law does not give us access to the mindset behind the law or tell us why various (often fairly radical) legal changes were thought to be necessary.

Multicultural education does that. It spells things out in terms of a new morality, a new political psychology, and a new account of democratic pluralism. In doing so it never relies on the liberal democratic tradition and, indeed, at every step it breaks with and challenges the categories of the older traditional American way of looking at things.

Multicultural education compels us to reckon with the many deep and important tensions between the fight against discrimination and the liberal democratic political tradition.

ED: Your newest book is titled American Multiculturalism and the Anti-Discrimination Regime The Challenge to Liberal Pluralism. Let’s unpack that title – how do you define ‘multicultural education’ and ‘anti-discrimination’?

TP: Multicultural education can be defined historically as an education reform movement that grew out of the civil rights movement. The first time the term “multiculturalism” was used in its current form was in the context of American education debates of the 1960s, in a 1967 essay by Native American education writer and anthropologist Jack Forbes. (American multiculturalism is not tied at the outset to Canadian multiculturalism in any way.) The word “multiculturalism” is basically a positive way of saying “anti-discrimination.”

The anti-discrimination regime is everything we think of when we think of civil right reform. Here is a slightly modified version of a long paragraph from the book that summarizes it:

“Anti-discrimination politics appears as several different things that are all nevertheless connected. It comes to sight first as a moral commitment—our sense that racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination are unjust and that justice demands some significant effort to stand up to them. It is also obviously somehow a representation of the interests or claims or demands of the groups commonly thought to be the victims of discrimination in need of protection from it. It is, in addition, and very noticeably, a complex array of new laws and government institutions put in place to make the effort on behalf of those groups, and in the name of their moral claims, a reality. It is also a complex set of new ideas elaborating not just the new moral and legal requirements of the effort but other terms of social, psychological, and cultural description of the world needed to make sense of this new political commitment. Finally, it is an extensive project of cultural norm-setting and social institution-building undertaken by activist-leaders empowered and inspired by all of the above, a campaign that reaches from government to the universities to the professions—and to Hollywood, journalism, the military, even religion (what conservatives, borrowing from the neo-Marxists, now call the “long march through the institutions”). Taken together, these disparate elements provide, as the advocates of the fight against discrimination often say, a “lens” through which we are to see anew, perhaps for the first time truly, social life, democracy, and our world. It is this complex combination that justifies our use of the very old term “regime” and it is this that the study of multiculturalism, more helpfully than any other dimension of the whole, puts us in a position to see.”

ED: James A. Banks, “the father of multicultural education,” emerges as a central figure in your book. What drew you to his scholarship, and what do you believe was his most significant contribution to the field of education?

TP: Banks is the most widely-cited and prolific of all multicultural education writers. I disagree with Banks fundamentally on many things, but I found his work to be invaluable as a guide for thinking through the inner meaning of the civil rights revolution.

I found that he had written in very interesting and revealing ways about the hopes and assumptions of civil rights politics without being so radical as to be unhelpful.

TP: I had looked at political theorists like Iris Marion Young who offered general “political theory” accounts of the “politics of difference.”

But Young, like other similar political theorists, makes it hard to see the simple political teaching at the bottom of things. (In the case of Young in particular, she actually starts from criticisms of anti-discrimination law—but that is very misleading because her ultimate position is simply a radicalization of anti-discrimination commitments.)

As an education reformer, Banks always spoke to the American community as a whole. What he says is ultimately deeply “radical,” but then what Banks teaches is precisely the radical character of civil rights politics as such. Banks offers direct access to something that we will miss if we begin from better-known (and perhaps seemingly more “sophisticated”) theorists. Though he is not as famous as Noah Webster, he is comparable to him in that he serves as a very useful touchstone by which we may see into the moral and political outlook of democratic life (as much as it may drive my fellow conservatives nuts to hear me suggest such a comparison). Certainly, I know of no more useful guide to the thinking of our post-anti-discrimination world.

Did you know?

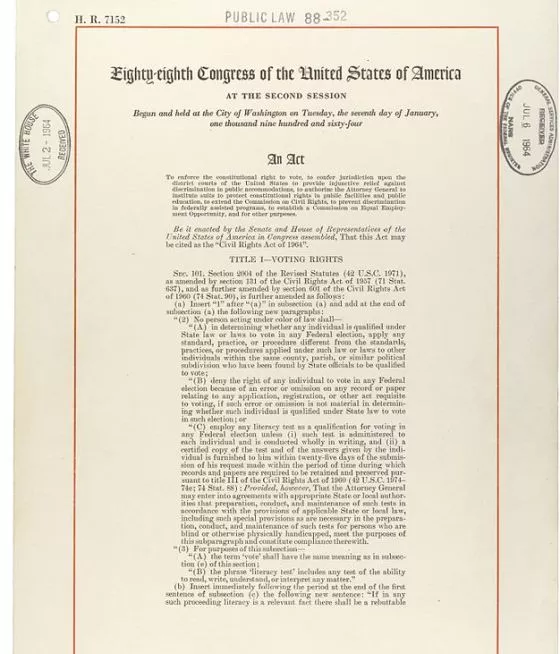

ED: Why do you consider the Civil Rights Act of 1964 a “crucial turning point,” and what unforeseen consequences occurred in the United States as a result?

TP: A big question and so a couple of broad answers. (This is the general question of the book.)

One way to measure the change wrought by the 1964 Act is to contrast it with our traditional liberal democratic understanding of things. But here we have to speak not just of the 1964 Act, but of all the other civil rights laws that came immediately after—and the significant reinterpretations of the law that followed as well. (For example, nobody thought in 1964 that civil rights law banned the use of “stereotypes” or regulated harassment or the “hostile work environment”; those changes came a couple decades later.) It is very basic to our situation today that the authors of the 1964 Civil Right Act had no clear idea what they were unleashing when they proposed the law. Certainly nobody could have predicted our experience under the law in the six decades since.

TP: Anti-discrimination politics offers several major challenges to the liberal democratic understanding of things, challenges that were not posed by earlier reforms (like the New Deal, say).

First and most importantly, anti-discrimination challenges the liberal view of the relationship between morality and politics: the idea that legislating morality is wrong (the liberal view) is challenged by a new politics that puts basic questions of morality at the center of things.

Second, anti-discrimination regulates our interpersonal relations, how we are to treat one another. This is very explicit in the law’s regulation of the workplace, schools, public accommodations (hotels, restaurants, etc.), and neighborhoods (in housing laws). Civil rights law directly governs our “social” relations in a way that the New Deal never tried to do.

Third, anti-discrimination offers a new formula for thinking about pluralism or “group politics,” one that differs from the liberal tradition in many ways—above all, by requiring a much more interventionist and hands-on management of things by the state (this is one way of stating the difference between “multiculturalism” and traditional liberal “pluralism”).

Fourth and finally, and this is of course the most obvious and noticeable change, anti-discrimination politics challenges our liberal commitment to freedom of speech (I note in the book over a dozen kinds of anti-discrimination policies that restrict speech). All of these challenges can be summarized by reference to a wide-ranging assault on the liberal public-private divide. (There is much to admire in Christopher Caldwell’s treatment of these issues in The Age of Entitlement, but his reduction of the liberal tradition—and of the question of anti-discrimination’s challenge to it—to the issue of “freedom of association” is a real limitation.)

What then should we say about anti-discrimination on its own terms, and not simply in relation to the liberal tradition? That is much harder to say because we are in uncharted territory. I do think that anti-discrimination politics is ushering in a new kind of understanding of democracy and is shaping a new kind of modern democratic “citizen.” It ought to be the challenge of every political scientist today to try to come to terms with and give an account of this broad development; amazingly, this is not even a question for political science today (mainly, in my opinion, because political scientists are too busy doing the new order’s work).

In the book I emphasize two dimensions of this question. First, the new form of group-politics is much more contentious and combative and, at points, spirited and angry. It has a new sensibility that I believe is shaping our politics at a basic level, and not generally for the better. This new view of things is very different from the deliberate efforts of the liberal tradition to tame group politics (its morality of toleration, its soft skepticism, its view of groups as “factions,” its political prescriptions like the separation of groups and state or the public-private divide—which I summarize in chapter 7 of the book).

Another, second, way of looking at this is by exploring the new “moral” outlook of civil rights politics. There is a whole constellation of moral categories—identity, inclusion, recognition, respect, equity, social justice, etc.—emanating out of the civil rights revolution.

To the extent that democratic citizens adopt and absorb these categories, their view of the world and their character will be shaped by them. Once again, I note what I believe is a very combative, spirited element of the new morality as well, a morality rooted finally in corrective justice. I have my doubts about whether corrective justice, especially group-based corrective justice, can form the basis of a healthy democratic political life.

ED: What does your book’s subject matter reveal about America’s founding principles and history?

TP: As my summary of the liberal tradition (chapter 7) and my contrasting account of things at the level of “group politics” (chapter 8) and at the level of our public morality (chapters 9 and 10) indicate, the liberal democratic understanding of politics, political morality, and group politics offers many lessons that we need urgently to relearn.

ED: What is your next project?

TP: I’m working on a study of Canadian multiculturalism policy and I’m also starting to write about how we might think about reforming our civil rights laws and make the civil rights regime less punitive and less likely to encourage group conflict and mistrust.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about the American political tradition?

TP: There’s more to the “liberal” tradition than laissez-faire capitalism or “libertarianism. This is something that the liberal pluralist tradition has taught me. Liberal pluralist thinking (Locke’s Letter Concerning Toleration, Madison’s 10th Federalist, etc.) contains a lot of political wisdom—yet it is agnostic on the question of “free markets” and the regulation of “property.” This means that both the Left and the Right today can learn a lot today from the American founding as we try to sort out the vexing questions surrounding “identity politics,” the “politics of difference,” and the civil rights revolution.

ED: Thank you for your fascinating insights!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).