An interview with Professor Michael Breidenbach

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Michael Breidenbach to discuss religion in colonial America, in particular, how early Catholics grappled with political allegiances in a Protestant world. Dr. Breidenbach is an Associate Professor of History at Ave Maria University and a Senior Affiliate for Legal Humanities at the Program for Research on Religion and Urban Civil Society at the University of Pennsylvania.

ED: What inspired you to become an American historian?

MB: I once heard the story of a journalist who asked a mountain climber why he started to climb. The mountain climber asked him in reply, “Why did you stop?” The mountain climber’s point was that everyone naturally begins his or her life climbing—the cause of much anxiety for parents!—but that most people stop at some point.

The mountain climber is just someone who keeps climbing, and I feel the same way about learning history. I was naturally curious about the history of where I call home, so I wanted to keep learning.

My challenge to many Americans is: Why did you stop?

MB: I became an early American historian in Britain. Some friends called this ironic, and I think they were wiser than they knew. Studying at the University of Cambridge gave me a needed distance from the place I was studying: to ask new questions, find new sources, talk with those outside of America, and immerse in a culture that helped to form America but is distinctively different.

While living there, I experienced the quip, attributed to George Bernard Shaw, that America and Britain are two countries separated by a common language (including how to pronounce “Bernard”). They are also two countries separated by a common history in early America.

I became an American historian because I wanted to understand my country from the outside while still living in it. Historians often do the work of comedians, but with thesis statements rather than punchlines. In my work, I take a familiar idea or event, view it from the outside, and thereby offer a new way of looking at it. In that sense, all history is ironic.

ED: What led you to write your book?

MB: Writing a history of historical writing is another irony of the discipline. It’s clear how my book, Our Dear-Bought Liberty, ended: it was published in May 2021. But how did it begin? The genesis of a book, like the history that it tells, is complex.

I grew up at the dawn of the Information Age, the terrorist attacks on September 11, and the world becoming “flat.” Perhaps because of these world-historical developments, I became interested in multi-layered loyalties and the complexities of patriotism in an interconnected age. That interest led me to investigate the ironic symbol of an American flag made in China. While in college I traveled to China to talk with manufacturers of these flags and interviewed U.S. politicians who sought to ban their importation. (The result of that research was published in The Atlantic.)

When I arrived in Cambridge, I began studying how religious minorities in the eighteenth century, in an age of global commerce and revolution, reconciled their civil loyalty and religious commitments. At that time, nearly every Western country had an established state religion. So how could religious believers who did not conform to the established church still love and be loyal to their country? Should the establishment recognize them as full members of the political community despite their religious differences? In particular, I was interested in how Catholics in early America navigated their dual allegiances in an English Protestant empire.

As I visited and researched in the cities where these early American Catholics had traveled and studied—Paris, Rome, Liège, London, Bruges, and Baltimore—I increasingly identified with my subjects: young Americans studying in Europe and attempting to reconcile their national, political, and religious identities at great distance from their native origins. As many authors realize in an honest moment, I was also writing for myself.

ED: Why do we need to read your book?

MB: Most Americans are familiar with the story of religious minorities who immigrated to America to flee from religious persecution. These pilgrims established a small settlement and later founded a prosperous republic. They formed a church free from what they considered to be the papal perversions of their faith. These faithful fought for American independence and codified constitutional guarantees of religious liberty. That history, we are told, is a Protestant one. Our Dear-Bought Liberty tells this familiar tale, but with Catholics as founders and framers of the United States. It’s the history of how Catholics negotiated their dual allegiances in a country that was hostile to their faith, and how they offered a unique contribution to religious liberty in America.

What explains the remarkable transformation of Catholics being suspected subjects of a Protestant king to trusted citizens of the American republic? I argue that Catholics became American by declaring independence from the pope. They rejected the two beliefs that had made Catholicism politically intolerable: that the pope’s spiritual and moral teachings can be infallible, and that he holds the authority to intervene in the temporal affairs of other countries, including the right to depose civil rulers.

Catholics of this sort were not a foil to American religious and political arrangements. Instead, they fit their beliefs within the ideologies of the American founding and thereby answered Protestant charges that Catholics should be legally penalized. Once considered lawbreakers, they became lawmakers.

Framing the story this way challenges some of the most deeply rooted assumptions about America’s “first freedom” of religious liberty and church-state separation. It also questions the grounds on which American Catholics have celebrated the compatibility of their faith with their country. Along the way, it offers new archival evidence on the founding of Maryland, the Catholic contributions to religious toleration in colonial America, and the surprising Catholic influences on the American founding.

ED: What does your book’s subject matter reveal about America’s founding principles and history?

MB: One of the founding principles of America is religious freedom. There’s a common assumption that American religious freedom is based on Lockean principles, yet John Locke wrote that a state should not tolerate Catholics, so if there are Lockean sources of American religious liberty, we need to explain the reasons why Catholics were included. Certainly American and French Catholic support during the Revolutionary War softened anti-Catholic prejudice in America. But the extension of religious liberty to Catholics was not just a one-sided process in which liberal or enlightened Protestants and Deists deigned to grant liberty to Catholics. Catholics were also important contributors to religious liberty throughout the colonial era and the early republic.

Our Dear-Bought Liberty shows that American religious freedom has many intellectual and practical sources, but we often miss an underlying principle: loyalty before liberty. Americans needed to pledge their loyalty before they could enjoy their liberty. The reason why Catholics could pledge uncompromised civil allegiance to the United States is because of their denial of papal claims to spiritual infallibility and to temporal power in other countries—claims that, Locke argued, had made Catholics intolerable.

Our Dear-Bought Liberty also advances our understanding of America’s founding history. It tells the story of how the Catholic founders and leaders of Maryland, George and Cecil Calvert, advanced important elements of church–state separation, including no established church or sectarian oaths for public office. Additionally, Maryland Catholics issued the first comprehensive religious toleration law for Christians in English history, codifying the “free exercise” of religion.

My book also shows how Catholics were important supporters of American independence and the new republic. The Continental Congress tasked Charles Carroll of Carrollton and his second cousin, Bishop John Carroll, with gaining Canadian support for American independence from Britain. Charles Carroll was the only Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence, and many Catholics served as soldiers and officers in the Revolutionary War.

John Carroll’s brother, Congressman Daniel Carroll, joined James Madison in supporting the First Amendment, and, as a senator, Charles Carroll was on the committee that finalized the text of the First Amendment. John Carroll’s former student, the Catholic reporter Thomas Lloyd, wrote Congress’s official record of the drafting history of the Bill of Rights. This historical revision challenges long-held assumptions that Catholics were at odds with American church-state arrangements and shows Catholics’ unique contributions to American political culture.

ED: What is your next project?

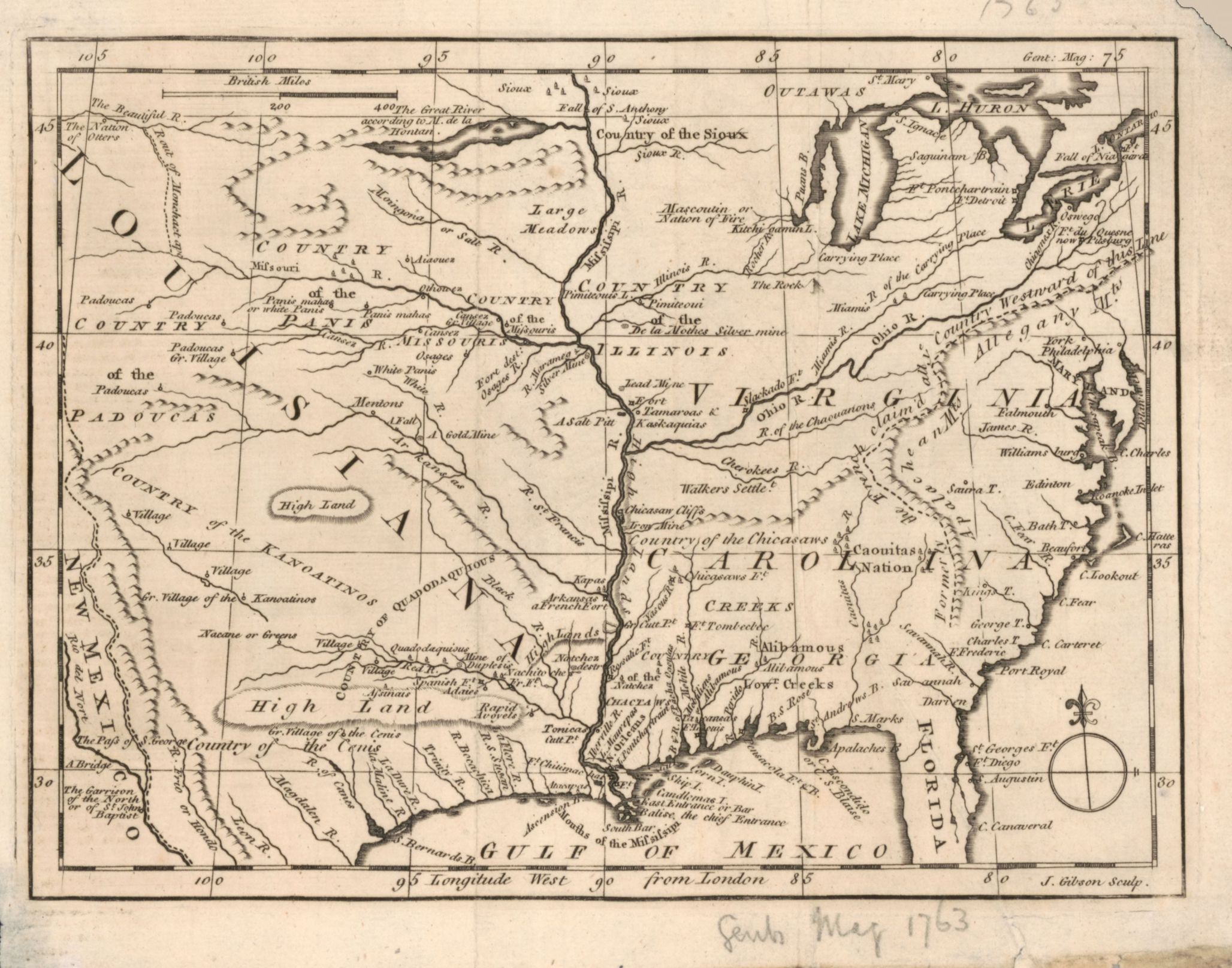

MB: One of my new projects is Naming the New World: Liberty and Language in Early America. It’s the story of how early Americans created a new country by naming and renaming the world around them—from territories, titles, and towns to religions, races, and revolutions. Colonial settlement and the founding of a nation presented Americans unparalleled possibilities to inscribe their languages, politics, cultures, and religions into the land. Americans created new names to mark their republic (Washington, DC) even as they preserved names that marked their royal past (Jamestown) and appropriated names from peoples they dispossessed (Massachusetts).

One part of the study that I’m working on now is the political implications of naming in the revolutionary period and early republic. Naming could be very political: the labelling of even non-political things, like a newly discovered planet named after King George III, became embroiled in revolutionary politics. Whereas French revolutionaries renamed everything from cathedrals to calendars, the American revolutionaries, with a few conspicuous exceptions, retained many royalist and aristocratic names. Americans saw their revolution as continuous with British history rather than an abrupt departure from it.

This project comes at an interesting time as people attempt to rename the world around us. Such efforts may be seen either as political projects to reimage a more egalitarian future or as exercises in damnatio memoriæ, the condemnation of memory. My work suggests that controversies such as these rest in large part on who has had the authority to name. No longer was naming in early America the provenance of cartographers and colonizers. Indeed, efforts to democratize naming authority can be detected as early as colonial America, where local people exercised the power to name their own community and the things in it. These dynamics of state building and cultural development enjoin us to consider the relationship between language and liberty.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about American history?

MB: American history is increasingly politicized and polarized, so what we need most are certain virtues for historical learning. To rephrase St. Francis of Assisi’s famous serenity prayer, we need the humility to accept the facts that cannot change, the courage to interpret them, and the wisdom to know the difference.

ED: Thank you for your insights and time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).