An interview with Professor Maura Jane Farrelly

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Maura Jane Farrelly. Dr. Farrelly is associate professor and chair of American Studies at Brandeis University.

Motivated by their faith

ED: What inspired you to become an American historian?

MJF: The summer after I was in 9th grade, my parents took my siblings and me on a vacation to Massachusetts. We went on a whale watch in Provincetown and spent an afternoon in the cemetery in Plymouth. I knew then that I was going to be a marine biologist or an American historian. My senior year, then, I took organic chemistry. And I became a historian.

ED: What do you consider an underrated moment in the American founding?

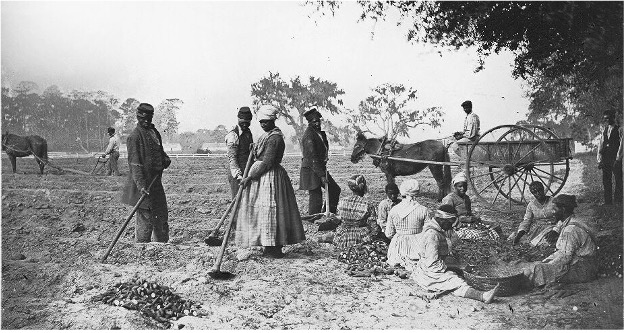

MJF: I’m not sure I would say it’s underrated, but I would say it’s profoundly misunderstood — and that is the decision of the Constitutional Convention to adopt the 3/5 clause. It is sometimes presented as a provision that “defined Black people as 3/5 human.” I certainly understand the rhetorical power of parsing the clause in that way — and the greater truth that such a parsing asks us to confront about the legal and social status of Black Americans at the time of the Founding is important.

But I always remind my students that South Carolina’s delegates would have been more than happy to have the people they owned count as 5/5 of the population, as far as determining the size of their state’s congressional delegation was concerned. The 3/5 clause was designed to give property — or wealth, really — some kind of representation in Congress.

No state, not even Massachusetts, had spent more money on the American Revolution than South Carolina. But a majority of that state’s residents were Black. South Carolina’s wealthy White delegates wanted to know that their disproportionately large contributions to the founding of the nation would have a voice in Congress.

In that sense, the 3/5 clause is not unlike some of those memes you’ll see floating around on the internet today, comparing the amount of money that states like New York and California contribute to the federal coffers to the amount contributed by states like West Virginia and Mississippi. The implication is that the opinions of New York’s and California’s lawmakers should therefore matter more.

ED: How did the early Catholics of Maryland contribute to American identity?

MJF: I guess I would say they contributed by being a fantastic example of how the American context changed European identity into something altogether different. Thanks to religious discrimination, English-speaking Catholics in colonial America had to actively choose to be and remain Catholic, in a way that their religious counterparts in Catholic Europe did not.

They had to take responsibility for their religious identity, and this gave them a sense of ownership over that identity (and the priests who helped them to maintain that identity) that was really lacking among Catholics in the predominantly Catholic countries of continental Europe.

The American context turned British colonial Catholics into fierce republicans who felt entitled to tell their clergy what to do (in the same way they felt entitled to instruct their legislators).

That some of the most meaningful and lasting changes in America’s history were brought about by people who were motivated by their faith.

ED: What has your research taught you about faith-based efforts to drive meaningful historical change in the United States?

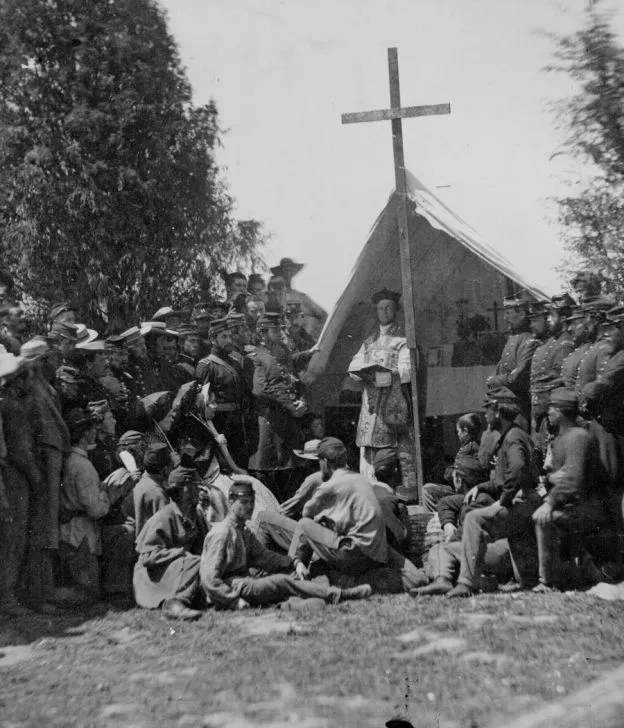

MJF: Whether it was abolitionists in Boston who opposed the Fugitive Slave Act, or child welfare advocates in New York who worked to get children off the city’s streets, or settlement house residents in Chicago who pushed for the direct election of senators and a federal income tax, all of these people were motivated by a sense that they had an obligation to humanity that was rooted in their obligations to God.

Certainly there is much damage that has been done — in the United States and elsewhere — by people who were motivated by their faith.

But that’s the thing: whether the change was good or bad, if it truly transformed the culture in some way, there was often a person of faith involved — someone who had a sense that he or she was acting in the name of something greater than themselves.

ED: While a minority during the colonial era, by 1850 Roman Catholics were the largest single denomination in the United States. How did American Protestants respond to this demographic shift in the 19th century?

MJF: The same way they respond to massive demographic shifts today — with a great deal of angst, hyperbole, hypocrisy, and violence. I’m not sure how much I can say in such a short space, but there’s nothing new about the animosity that some native-born Americans feel today toward the immigrants in their midst.

Whether it was the French in the late 18th century, or the Germans in the early 19th, or the Irish in the mid 19th, or the Italians and the Chinese in the late 19th, or the Jews in the early 20th, or the Japanese and the Indians in the mid-20th, or the Mexicans in the late 20th, or the Central Americans and Middle-Easterners in the early 21st, the fear has always been the same: These people are going to change American culture.

And guess what? That fear has never been unfounded. Immigrants have always changed the culture — and they always will. They are the scrappiest, cleverest, hardiest people in the world, and they have made America great.

ED: Describe your favorite research “rabbit hole,” and the results of that quest.

MJF: Tracking down the average menu price for terrapin during the Gilded Age and discovering that at one point it soared to an astonishing $6 per dish — the equivalent today of about $170. I also spent a ridiculous amount of time once studying the history of the wild blueberry industry in Maine.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

MJF: That those founding principles are the only source of authority we really have for making some of the social justice claims being made in America today — and I worry that many of the young people pushing for reforms that I happen to agree with fail to see that truth. I mean, if you’ll work for me for $8 an hour — a wage that, at 40 hours a week, won’t enable you to feed your family or pay your other bills — why should I pay you $15?

Someone coming out of a faith tradition like Christianity or Judaism might say “because human beings are created in the image and likeness of God.” You pay a man or woman a living wage because there is that of God in him or her. Of course, that argument doesn’t gain too much traction in a lot of circles today. So this begs the question of why I should feel so obliged.

Growing up in the American school system, many of us made a pledge every morning in which we promised to seek “liberty and justice for all.” That promise was supposed to reflect our commitment to America’s founding principles — principles that were articulated by men who were inconsistent and hypocritical, just like we are. I would argue, however, that their hypocrisy ought not to undermine the power of the principles they articulated — especially since we really seem to have very little else to rely upon when making social justice claims.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

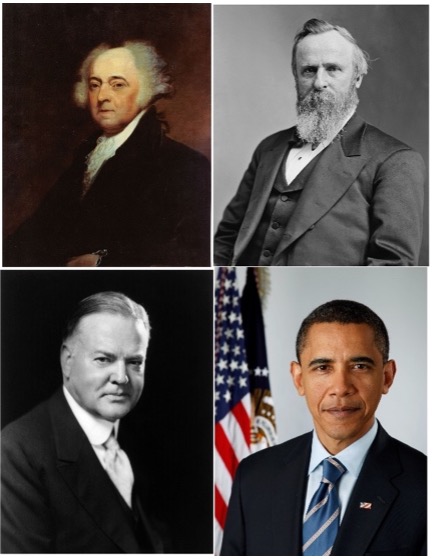

MJF: That John Adams was still alive when Rutherford B. Hayes was born; that Rutherford B. Hayes was still alive when Herbert Hoover was born; and that Herbert Hoover was still alive when Barack Obama was born. When you know that, you realize how young this country is — and why, then, we are still living with the legacy of something like hereditary, race-based slavery. It was not that long ago.

ED: Wow, what a fascinating way to think about our young republic. Thank you for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).