An interview with Professor Mark David Hall

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Faculty Partner Mark David Hall to discuss his most recent book, Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land: How Christianity Has Advanced Freedom and Equality for All Americans. Dr. Hall is a Professor in Regent University’s Robertson School of Government and a Senior Fellow at the Center for Religion, Culture, and Democracy.

All possess alike liberty and conscience and immunities of citizenship

ED: Thank you for taking the time to talk about your wonderful and engaging book! Explain how you came to this project, and what sorts of questions guided you during your research.

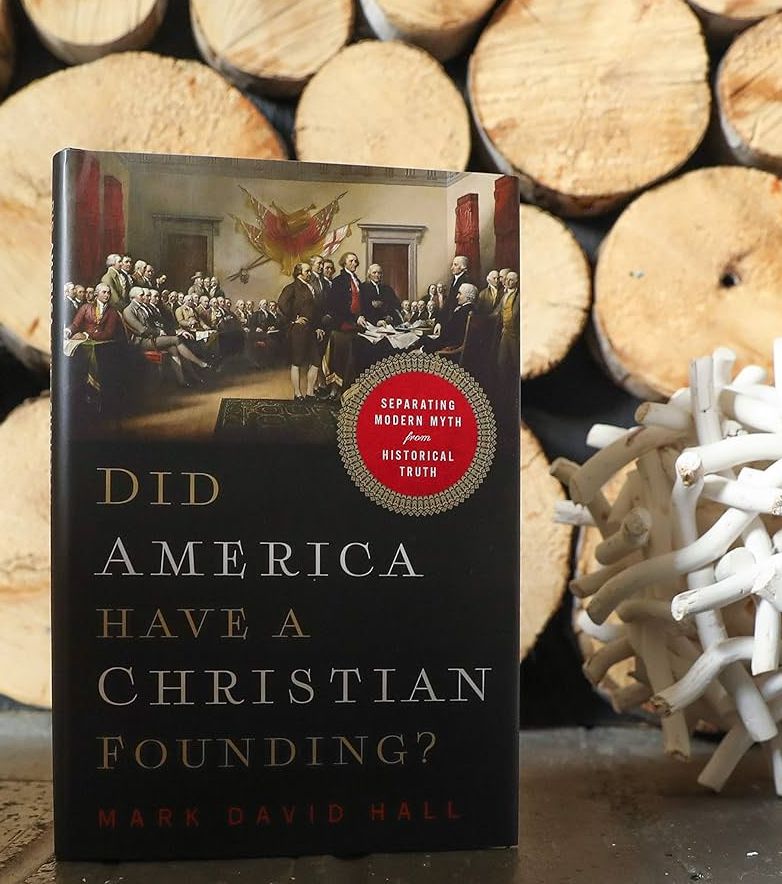

MDH: This book was originally conceived as a sequel to my last book, Did America Have a Christian Founding? (Nashville: Nelson Books, 2019). In between the publication of that book and this one, the 1619 Project came out and it made me angry as it was such a profound distortion of American history. For years, academics have been arguing that slavery and racism are central to the American story. And they often suggest that most Christians supported these evils, and that for progress to be made we had to overcome traditional Christian teachings, maybe by rejecting religion altogether, or at least by embracing a progressive manifestation of it. I acknowledge that Christians throughout American history have defended evils such as slavery, racism, and sexism, but I wanted to tell a different story.

My argument is that, on balance, Christianity has been a force for the advancement of liberty and equality from the Puritans to the present day.

ED: The Establishment Clause is one of the most disputed features of the Constitution. Why has this been the case and what, exactly, does it prohibit?

MDH: I fully support interpreting constitutional provisions as they were originally understood by the drafters and ratifiers. I argue in some detail in my last book, Did America Have a Christian Founding? that the Establishment Clause essentially means what it says, i.e., that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” Simply put, it prohibits the establishment of a national church. States could and did have established churches at the state level. Fortunately, from my perspective, they voluntarily disestablished them.

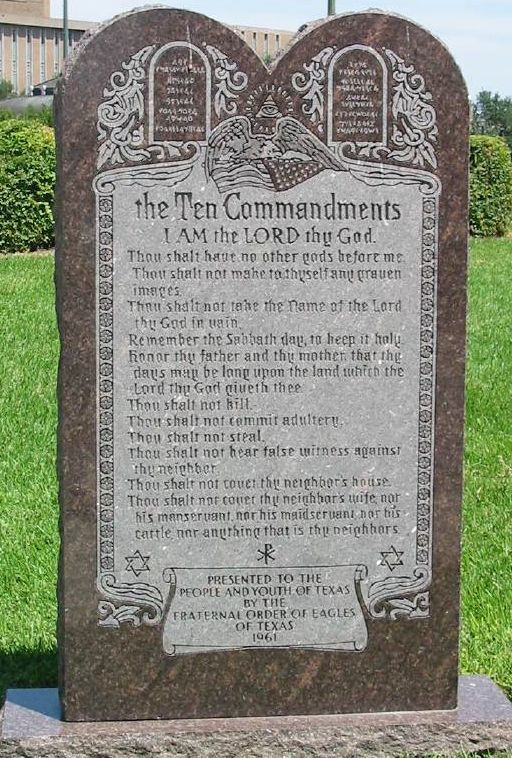

Through the 14th Amendment, the Establishment Clause came to be applied to the states. After 1947, states could not have official state churches either, but this left a lot of room for state governments and for the national government to do things like create monuments that include religious imagery or language (such as a monument of the Ten Commandments). It also permits them to create exemptions or accommodations that protect religious citizens. Congress did this in the Selective Service Act of 1917. Basically, it said if you are a member of a historic peace church and are a pacifist, you don’t have to serve in combat.

Did you know?

This exemption was challenged on constitutional grounds, including that it was a violation of the Establishment Clause. But in no way, shape, or form can the original understanding of the Establishment Clause be understood as prohibiting Congress from protecting religious citizens—even members of select churches. Fortunately, in 1940 Congress expanded this protection to include all religious citizens, and to this day the Selective Service Act protects only religious pacifists. In my opinion, it should be expanded to protect citizens who are pacifists for non-religious reasons, but that it hasn’t still doesn’t constitute an Establishment Clause violation.

There has been a great deal of confusion over what the Establishment Clause prohibits because in 1947 the Supreme Court properly insisted that it must be interpreted in light of the founders’ views, but then provided a very skewed account of their views. Both Justice Black and Rutledge emphasized Thomas Jefferson‘s letter to the Danbury Baptists, where he asserts that Establishment Clause creates a wall of separation between church and state.

If you believe there’s a wall of separation between church and state, then you might come to the conclusion that religious accommodations that protect pacifists are unconstitutional, that monuments including religious language are unconstitutional, that public funds going to private religious schools are unconstitutional. But if you accept an accurate historical account of what the Establishment Clause was intended to prohibit, all these things are clearly permissible. Now we just need to argue which are prudential and which are good public policy.

ED: In your opinion, which Supreme Court ruling (or rulings) embodies the tension of placing religious monuments and speech on public land?

MDH: Beginning in 1947 and through the 1970s, a majority of justices accepted the view that there was a wall of separation between church and state. And so, there are a variety of decisions limiting the sort of aid that states could give to religious schools and serious questions about religious monuments and public land. A good example of a problematic case involved a massive monument of the Ten Commandments on the Texas State House grounds and a plaque containing the Ten Commandments in a Kentucky courthouse. Both displays were challenged as violating the Establishment Clause, and you would think that justices would either hold both of them to be constitutional, or both of them to be unconstitutional.

In fact, four justices believed both were unconstitutional and four justices believed they were constitutional. Justice Breyer cast the deciding vote, counterintuitively upholding the massive monument on the Texas State House grounds and declaring the plaque to be unconstitutional. Kind of a crazy decision, in my humble opinion. Fortunately, we’ve seen that the Court has shifted to embrace a more accurate view of what the founders understood the Establishment Clause to prohibit.

A couple years ago, there was a case involving a massive 40-foot cross put up in a county in Maryland to honor the lives of men from the county who had died in the first World War. The cross was put up with private funds on private land, but eventually it came to be in a public land. The American Humanist Association said, “this cannot be, you cannot have this religious symbol on public land.” Yet the exact remedy was unclear. What are we going to do, decapitate it, so it becomes like a like the Washington Monument, or maybe tear the whole thing down? Fortunately, the Supreme Court said that in no way was this 1925 monument an establishment of religion. The Court said that by a vote of seven to two, even Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan joined the “conservatives,” for want of a better word.

It is important to note that when the cross was erected, there is no reason to think that any of the young men from this county who died in the Great War were anything other than Christians. America was still mostly populated by Christians in that era; probably 94% of citizens would have identified themselves as some sort of Christian. But in the 2020s we obviously live in a far more pluralistic country.

So, erecting a cross to honor dead soldiers in World War One wasn’t a bad idea, but would be a horrible idea today. There’s a very good chance that many soldiers who died in, say, Iraq, would not identify themselves as Christians, and so you wouldn’t want to honor them with a Christian symbol. On the other hand, maybe you’d want a monument that has religious symbols from a variety of traditions. If you go up to the 9/11 Memorial, you’ll see crescent and stars, crosses, and a Stars of David, and so it’s very pluralistic.

ED: What does the history of religious liberty in America reveal about America’s founding principles?

MDH: America’s founders were committed to very robustly protecting religious liberty, and many of them referred to it as “the sacred right of conscience.” And they were coming to recognize that religious liberty applies equally to everyone. The Constitution famously bans religious tests for office, and the anti-Federalists pointed out that a Jew, a Muslim, or even an atheist could become president. The Federalists had to admit that was a possibility, but they usually went on to say but it would never happen.

They were unable to recognize what the United States of America would become, but still, the fact is that that principle is inserted into the Constitution itself.

As well, the Constitution’s oath provisions all permit oath takers to swear “or affirm.” The affirmation possibility was included to protect members of small Christian sects, such as Quakers, Mennonites, and Brethren, who believe that they cannot swear oaths, but they may affirm them. It is noteworthy, I think, that a religious accommodation is baked into the Constitution itself.

One of my favorite letters from the founding era is George Washington’s letter to the Hebrew congregation in Newport, Rhode Island. He explains that in America, we no longer speak of religious toleration. Instead, everyone has a natural right to worship God according to the dictates of conscience and, we might add, to act upon his or her religious convictions whenever possible. Collectively, the founders were very concerned for religious liberty, and they wanted it to be robustly protected. Thank goodness they were coming to recognize that everyone enjoys their rights to religious liberty, not just Protestants, and not just Christians.

Now, let me hasten to say that we have not always lived up to this founding ideal, and there has been far too much persecution or harassment of religious minorities throughout American history. I have an entire chapter detailing the profound anti-Catholic animus that existed in the mid-19th to mid-20th century and how it led to this idea that there should be a strict separation between church and state. Fortunately, we overcame that in the mid-20th century. I like to think we still have a pretty profound commitment to religious liberty. I’m afraid some of my progressive friends have turned against religious liberty, especially when it comes to conservative persons of faith who believe, for instance, they can’t participate in the same-sex wedding ceremony or perform an abortion. But other than that, I think it’s fair to say we still have a pretty robust understanding of religious liberty that must protect everyone, and it should permit people to act upon their religious convictions and not just engage in worship.

ED: What’s next for Mark David Hall?

MDH: I’m spending the year at Princeton at the James Madison fellowship, and I’m writing a book on American Christian nationalism. This topic has been very hotly contested over the last couple of years. Basically, I’m attacking the critics who vastly exaggerate the threat of Christian nationalism today, but I also critique the handful of Christians that actually embrace Christian nationalism. I think all manifestations of the phenomenon are problematic. I’m hoping that the book will be out early next year.I should also mention that I’ll start teaching at Regent University this fall. The Robertson School of Government is starting a PhD program in politics, and they asked me to be involved in it. I hope anyone interested in this program will reach out to me, I would be happy to discuss it.

ED: Sounds like a fascinating project! And congratulations on your new position! We look forward to speaking with you soon.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).