An interview with Professor Jonathan White

We are excited to announce that JMC Miller Fellow Jonathan White has been named a co-recipient of the prestigious 2023 Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize for his recent book, A House Built by Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House. JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager Elliott Drago sat down to interview Dr. White earlier this May.

There was no color line in Lincoln’s White House

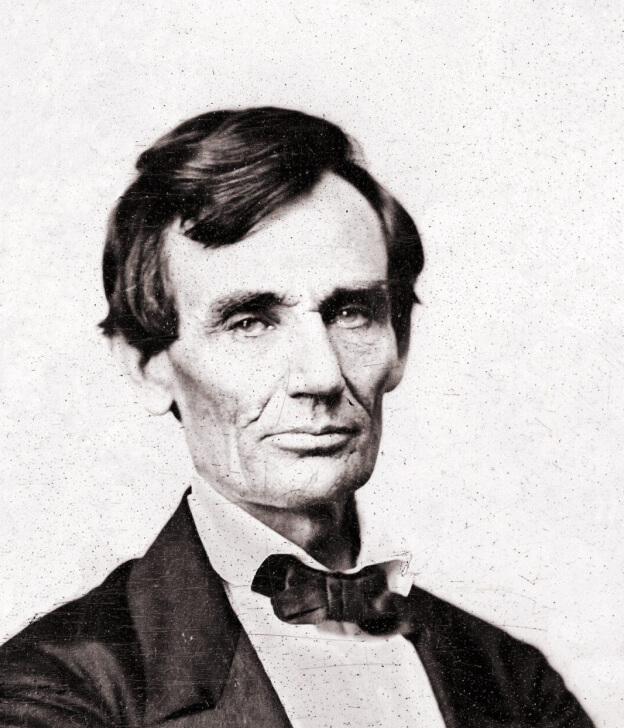

ED: Thank you for taking the time to discuss your tremendous and important book! Many Americans may not realize how Abraham Lincoln’s meetings with African Americans at the White House had a major impact on his political career and life. Can you explain how you came to this project, and the types of sources and questions that drove your research?

JW: I started collecting letters from African Americans to Lincoln in 2014. These correspondents saw Lincoln as a president who was concerned with their lives and with what concerned them. I put the letters into a book called To Address You as My Friend: African Americans’ Letters to Abraham Lincoln (2021). A House Built by Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House (2022) grew out of that project. In these two books I wanted to recapture a historical moment, because today Lincoln gets a lot of criticism from many different areas of American society. Many African Americans today seem to have a sense of suspicion when it comes to Lincoln. But it hasn’t always been that way. When Lincoln died in 1865, African Americans mourned more deeply than white Americans did. And that was because of the relationship that had developed between Lincoln and Black Americans during the war.

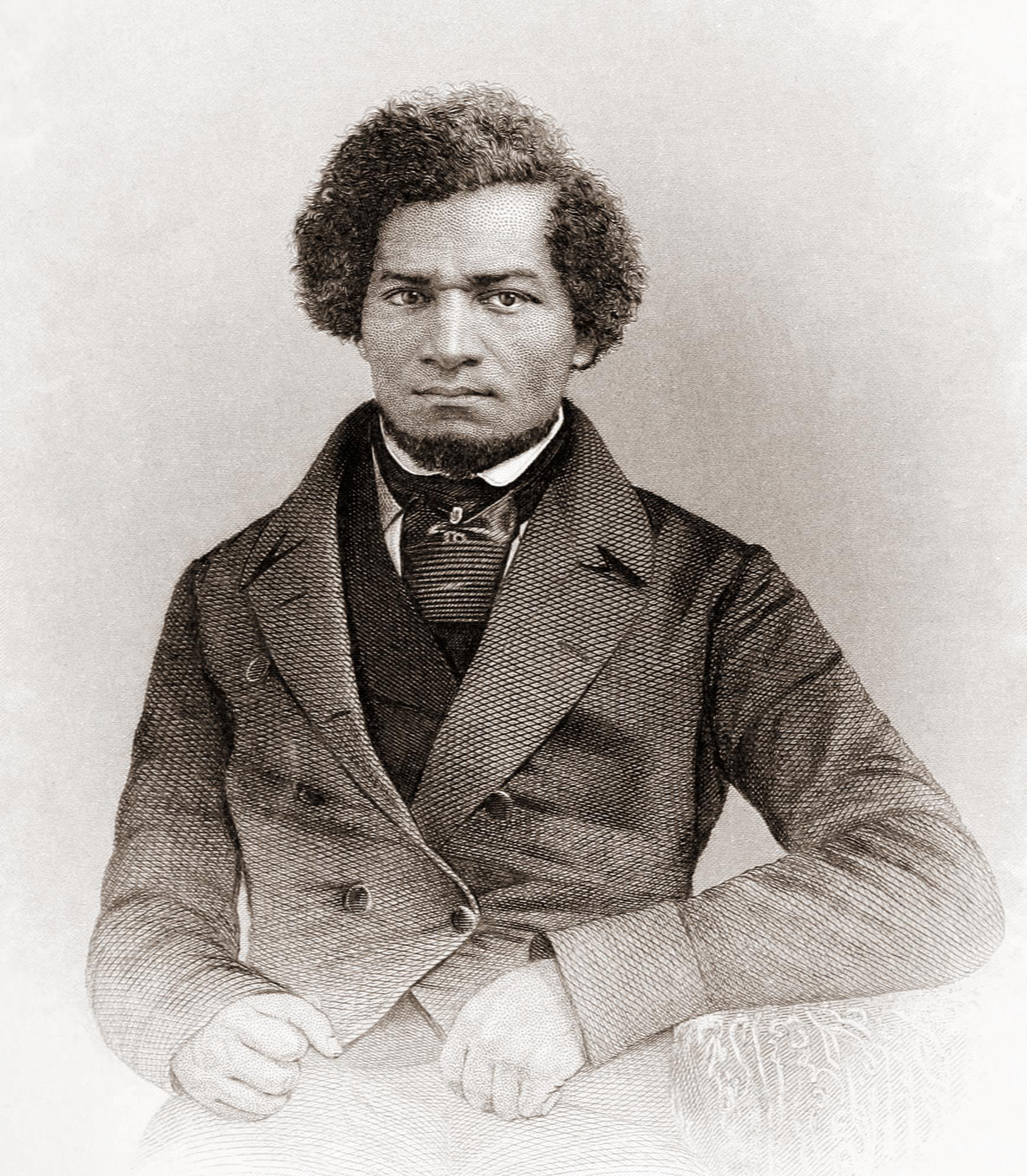

ED: You begin your book with a quotation from Frederick Douglass in which he says how impressed he was with Lincoln’s “entire freedom from popular prejudice against the colored race.” Yet their relationship was not always so sanguine. Can you describe the evolution of Lincoln and Douglass’s relationship?

JW: Frederick Douglass was one of Lincoln’s harshest critics during the first half of the war. He thought Lincoln was too slow on emancipation. And even after emancipation, Douglass was angry that the War Department was not paying Black soldiers equally as white soldiers. He was also angry that the Union was not protecting Black soldiers from Confederate atrocities. So, in August 1863, Douglass goes to the White House and meets with Lincoln, where he pushes Lincoln on these issues. Lincoln’s answers are not altogether satisfactory for Douglass.

But Douglass is really moved by the fact that Lincoln does not treat him differently because of the color of his skin. They meet again in August of 1864 and discuss a way to try to free as many slaves as possible before the next inauguration because at that point, it looked like Lincoln was going to lose.

These personal interactions with Lincoln transformed the way Douglass viewed the president. He comes to see that Lincoln’s heart is fully in emancipation and that Lincoln is truly a great man.

ED: You take care to mention how Lincoln eagerly shook the hands of his Black guests. Why was that physical contact important?

JW: In the 19th century, most white people never would have shaken a Black hand. Lincoln was out of step with the norm, and I think it really speaks to his empathy—that he engaged with people and treated them as fully human on a personal level, whether they were famous or not. Sure, Lincoln is shaking Frederick Douglass’s hand, but he’s also shaking Black women’s hands out on the streets of Washington, or very poor, downtrodden refugees from slavery who are working in hospitals as cooks.

ED: One of the most evocative scenes from the book was when Lincoln received a special Bible from the Black community of Baltimore. Explain the circumstances surrounding the giving of that gift.

JW: The Black community of Baltimore wanted to show their gratitude to Lincoln, so they had a beautiful pulpit Bible made with a purple cover and a gold plate that depicts Lincoln freeing an enslaved man. They presented it to Lincoln in September of 1864 at the White House. One of the men made a short speech where he alluded to “The Star-Spangled Banner,” our national anthem that had been written in Baltimore during the War of 1812. And he also alluded to ideas about citizenship—that Black people wanted to be part of this national community.

They used the Bible as an opportunity to thank Lincoln for everything that he had been doing for African Americans during the war, but also to encourage him to work to bring African Americans more fully into the body politic.

“All men are created equal”

ED: How would you explain the relationship between Lincoln’s interactions with Black Americans and what Lincoln understood about America’s founding principles and history?

JW: I think Lincoln really believed it when he said that the Declaration of Independence applied to “all people of all colors everywhere.” For him, the principles of the Declaration were true, even though he knew they would never be upheld perfectly. But Lincoln always strove to make them more real. In 1857, Lincoln said that the founders didn’t need to write “All men are created equal” into the Declaration. Saying such a thing had nothing to do with achieving our independence from Great Britain. Lincoln said those words were in there for “future use.”

And Lincoln, I think, was that future use: He was the guy who was able to help make those principles more true or more real in the United States, and part of the evidence of that is how he treated African Americans.

ED: What’s next for Jon White?

JW: In August I’m publishing a book called Shipwrecked. It’s a biography of a man named Appleton Oaksmith, who was convicted of slave trading during the Civil War. It’s an extraordinary 19th-century adventure story that I use as a lens to explore the great lengths that Lincoln went to destroy the illegal transatlantic slave trade during the Civil War.

I’m also publishing an edited collection called Final Resting Places: Reflections on the Meaning of Civil War Graves with a friend named Brian Jordan. We gathered 29 historians, and each one wrote an essay about a grave site that’s meaningful to them. They are really powerful essays—one even brought me to tears recently—and it’s a beautifully illustrated book with about 120 images.

ED: Those projects sound fascinating! We look forward to speaking with you again soon!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).