An interview with Michael J. Douma

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Network Member Michael J. Douma. Dr. Douma teaches at the McDonough School of Business at Georgetown University, where he is the Director of the Georgetown Institute for the Study of Markets and Ethics.

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

MJD: Sometimes, I feel that I was destined to work with boxes. I had my first job at fourteen years of age, and I mostly sorted, folded, and placed papers in boxes for a printing company. My other teenage jobs included taking clothes out of boxes at a department store, and sorting machine parts into boxes at a light industrial warehouse. As an undergraduate, I worked for four years in my college’s archives, mostly sorting old papers, labelling them, and…naturally… putting them into boxes! I like to say then that I learned history from the primary sources, not from the textbooks. In fact, to this day, I have still never fully read nor have I required students to read an American history textbook. After years working in archives, I discovered it was more interesting to be a researcher than an archivist, that is, to take papers out of boxes rather than to put them in boxes!

Beyond these kinds of practical influences, I ascribe a real kind of Calvinist “calling” to my work as a historian. That is, I feel called to be a historian, and I think everything from solving puzzles to watching old movies as a kid led me in that direction.

I’ve always wanted to know the answers to things, especially about the history of my family and my community.

MJD: I have always enjoyed research and writing, and I have little sympathy for those who bemoan the “publish or perish” culture, because I see writing for publication as an essential and indeed enjoyable part of this line of work. It beats moving boxes all day.

ED: Many teachers introduce their students to three empires when studying the colonial era, i.e., England, Spain, and France. However, we know that the Dutch commercial empire played an outsized influence on those three powers and the colonial world in general. Why should we pay more attention to the Dutch colonial experience?

MJD: I suppose as a scholar of Dutch history, I ought to answer right away that of course we should give the Dutch colonial experience more attention. However, I also recognize that there is a limited amount of time in history classes and a limited amount of historical information students can digest. Every historian is fighting to draw more attention to their own interests. I suppose the Dutch colonial experience is worth highlighting however simply because it has been so understudied and there is still so much yet to learn. I have never been the type of historian to study what everyone else is studying. I don’t care to write, or in fact, read, another biography of Lincoln of Jefferson. I want to focus on neglected topics that might lead to new insights about the past. Dutch colonial history provides interesting parallels, examples, and counterexamples to British, French, and Spanish colonial history.

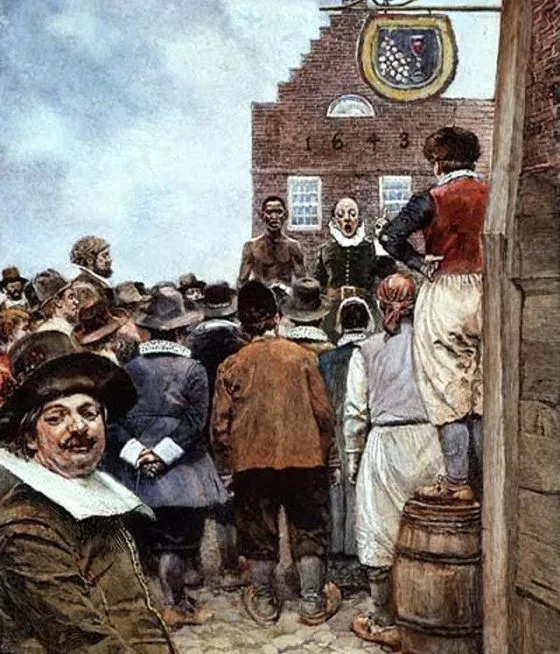

ED: Most Americans assume that slavery withered away in the northern colonies and states with little conflict. How does your work complicate how we understand slavery in northern colonies like New York?

MJD: Ideally, historians should not seek to complicate but rather clarify our understanding of the past. However, the past is always more complicated than we think. This presents a kind of paradox, that the further we dig into the past, seeking explanations, the more questions we have.

The history of slavery in the North is a particularly weak area of American historiography and is dominated by myths and misunderstandings. Myths from the Progressive Era established Northern slavery as mild, benign, and economically necessary. Every state and county history in this era excused local and regional slavery as a temporary anomaly.

The standard view of slavery and emancipation in the North is still wrong on many accounts. For example, contrary to the conventional view, slavery in the North was more commonly rural than urban. Prior to my recent work, there has been essentially no research on the demographics of slaves in the North. This has led historians to falsely assume that the Northern slave population grew largely on account of slave imports, when in fact, it appears that the domestic birth rate was quite high.

The number of slaves in the North was fewer than in the South, but slavery in the North was ubiquitous.

MJD: Slaves played an important, though not strictly necessary role in Northern labor. At times, market activity encouraged the growth of slavery, but markets also provided a transition for enslaved persons into free labor. It was not economics however, so much as a change of moral vision, expressed in anti-slavery politics and gradually built into the law, which lead to the death of slavery in the North.

The status of slaves in Northern states was also more complicated than many realize. Because each Northern state had its own timeline of emancipation and abolition, enslaved persons sought to escape to states which offered better protections. In this picture, there were various kinds of unfree people of different statuses. In New York, after 1799, there were thousands of children born to slaves, who were technically free yet bound to service until they reached an arbitrary age of adulthood, 28 for men and 25 for women. In New Jersey, there was a category of “slave for a term” after 1804. Census records and other contemporary evidence suggests that Northerners did not always clearly distinguish between the fully enslaved and those enslaved for a term. This was partially responsible for the apparent contradiction of slaves recorded in the census of Northern in years when legally there should have been no slaves in those states.

Finally, my book emphasizes that slavery in the North was much more Dutch than has been previously thought. Thousands of New York’s slaves, well into the nineteenth century, spoke Dutch as a first language or were bilingual Dutch-English speakers.

The past really is a foreign country sometimes.

ED: Tell us a bit about the process by which Dutch New Yorkers became a distinct group from their ancestors and families in the Netherlands.

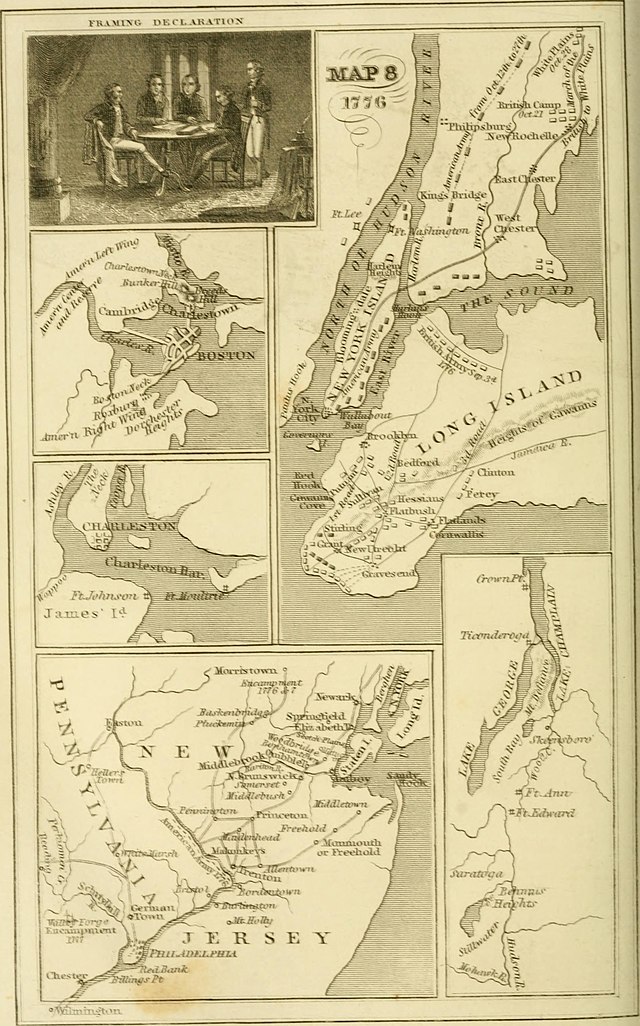

MJD: I wish I could give you a good answer here, but this is not really a topic that historians have spent much time answering. I begin my work roughly in the year 1700, some two generations after the transition of Dutch New Netherland to English New York. Probably the best work on this transition comes from Joyce Goodfriend, who has focused on the persistence of Dutch culture and language in New York City in the late 17th and early 18th century. My impression, beyond what I have gathered from Goodfriend’s valuable work, is that migration from the Netherlands to New York was fairly minor, although not completely absent from 1664 to say 1846, when a new wave of Dutch American immigration began. This meant that Dutch New Yorkers and New Jerseyans received some books, ministers, and new neighbors from the Netherlands, but only at a rate to keep them aware of their families across the ocean. Developments on the American scene, such as the Great Awakening, the American Revolution, and of course, the spread of American slavery, shaped a Dutch colonial culture that acted and thought differently than did the Dutch in patria.

ED: What were some of your favorite sources that you uncovered during your research? Which source surprised you the most and why?

MJD: At the beginning of this project, I expected to find account books with prices of farm products and lists of credits and debits of slave-owning Dutch farmers. I found very little of that kind of source material. Instead, I turned towards gathering data on a larger scale. I scoured sources for data on prices of slaves and farm commodities. I collected lists of runaway slaves. I looked for demographic clues beyond the historical snapshots captured in the census. In the end, much of my book’s argument is based on the data that I tediously sought out, compiled, and analyzed. This meant that I had to read up on disciplines that I was not trained in, such as statistics, econometrics, and demography.

Inspirational spotlight

I also found legal history sources to be quite useful in this project. Much of chapter six in my book is an argument built on a reading of individual slave cases in the New York courts. Historians before me tended to focus on the statutory law, while neglecting the common law. Statutory laws reflect the desires of politicians to shape society. They can ban slaves from going out at night, or they can ban slavery. But the common court cases reflect how the legal profession interpreted and applied the laws, and how citizens tried to get around them. Here, I discovered that the law in New York was gradually bent in the favor of the enslaved, so that in the 1780s, protections were built in again certain types of slave sales. Eventually, by the second decade of the nineteenth century, New York courts leaned towards emancipation and freedom as a default condition, requiring slaveowners to plead their case.

ED: How does your book augment our understanding of the economics of slavery in colonial New York?

MJD: I’m not sure that there was much of understanding of the economics of slavery in New York before my book. At least, I wasn’t able to find many sources that addressed this topic. The general view has been that slavery in the North, including New York, was economically marginal because there was no great staple cash crop such as cotton or tobacco in the South. I turn this “staple interpretation” on its head, showing that New York farmers profitably used slave labor to grow and sell wheat, but that slaveholding was ultimately a choice that transcended financial gain. In the 18th century, prices for slaves in New York were similar to prices for slaves in the South, but over time, the prices of slaves in New York decreased relative to those in the South. This indicates the gradually diminishing role of slave labor in the North, which was, I argue, largely a consequence of political changes, and was not due to the decline of wheat cultivation or alternative methods of growing wheat.

ED: Your book sets out to challenge and overturn assumptions about the history of slavery in New York. What types of assumptions did you hold at the beginning of your research, and did these assumptions change by the end of your research?

In the beginning, I really didn’t know whether I would discovered that slavery in New York had been economically viable or not. I didn’t and still don’t have a political or historiographical motive to argue one way or the other. As I began this project, I taught a few sections of a course on Slavery & Capitalism, for which I read extensively on the economic history of slavery. I was originally opposed to much of the research of the well-known Fogel and Engerman interpretation [i.e., that slavery was an economically rational institution], but over time I came to have more mixed reactions to their conclusions. Some of the more influential works for me were Christopher Hanes’ article on turnover costs and Gavin Wright’s work on slavery and property rights. These works convinced me that economic efficiency was not the essential concern here. Rather, in the study of slavery and economics, we need to understand, in addition to turnover costs and property rights, also the role of things like transaction costs, auction pricing, and expected returns and risks of investments.

I struggled mightily with what is called the “mild thesis.” This is the idea that slavery in the North was milder than it was in the South. At first, I turned against this view because there are so many clear examples of Northern violence against slaves and restrictions on their movement.

However, I couldn’t get around the fact that Northerners for generations believed their slavery had been milder. To me then, the real question was why did Northerners think this way, and only secondarily, was this rooted in any historical truth?

MJD: We should always condemn slavery, yet we need to study it dispassionately to understand it better. Chapter seven of my book, however, tries to explain how there was a kernel of truth behind the mild thesis, even though it was ultimately misguided and misused in the historiography. In short, the reason why Northerners thought their own slavery had been mild is because in its last generation, slavery had grown weaker and slaves had gained some legal rights. The first wave of historians who wrote about New York slavery lived in the shadow of the death of slavery. They knew stories of slaves from their parents and grandparents, who defended their own role in the story. Multiple layers of selection bias produced historians and histories that left out the worst elements of the past.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

MJD: It is clear to me, from my research, that principles of liberty emanated out of the Revolution. There were attempts to end slavery in New York in the 1780s, but resistance, particularly from the Dutch farmers in the state, was too strong. By the first decade of the 1800s however, even the conservative Dutch had to give way to the new ideas about liberty. Now, it is easy to point to the hypocrisy of a nation built on freedom, where slaves still resided. And, the old saying by Samuel Johnson still obtains: “Why do we hear the loudest yelps for liberty from the Drivers of Negroes?” However, it was precisely this contradiction between slavery and freedom that gradually wore down the old slaveholding morality and replaced it with a new anti-slavery order. These were not just the consequences of politicians reading John Locke and Cato’s Letters. The founding documents of the nation encapsulated these ideas and helped spread them, but ultimately the language of the language of the American revolution, and the mental and moral vocabulary that it ushered in, was a large-scale social movement that shaped the minds of lawyers, farmers, merchants, and even the enslaved themselves.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

MJD: This is a good question, but I reject the premise. Too often we think of history as a list of particular things that every student must know. I’m reminded of the old textbooks that used to say “Every schoolboy knows X, Y, or Z” in which X, Y, and Z are things that people today would think inconsequential and unimportant. When we teach American history through a canonical set of documents alone, we tend to propagate a singular view of the past, when I think it’s healthier for American society to entertain competing views of our national history. This came home to me over a decade ago when I spent a week grading essays of the U.S. AP History exam. I was disheartened but not surprised to discover that 90% of students taking the exam answered their essays in the same way, with the same political bent, even though the topics of the essays had multiple competing interpretations known to historians. It could not be the case that all of these students arrived at these similar conclusions on their own. Instead, it appeared that a main function, if not also the design of the AP History industry, was to inculcate certain views, not to teach critical thinking, per se.

ED: Thank you for your time and insights!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).