An interview with Matthew Young

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Matthew Young to discuss his work on toleration, hope, and the apocalypse. Dr. Young is an Assistant Professor of political theory in the Department of Political Science & Policy Studies at Elon University.

To cultivate a sense of hope

ED: What inspired you to become a political scientist?

MY: I have always been interested in understanding complex systems. As a young man in high school, I was interested in becoming an auto mechanic, for much the same reason—the complexity of the system. Yet human beings are far more complex than automobiles, and political science aims to understand what happens when eight-billion-odd human beings live in the world together, interacting with one another according to almost infinitely varied principles and values and material conditions. If you’re interested in complexity, there’s simply no better field to study.

I began studying political science, though, as an undergraduate at Berea College, where I fell in love with political philosophy. As the writer Glenn Tinder once explained, we engage in political thinking to reach answers that cannot be reached in any other way. As I studied politics I was captivated by a set of questions about politics that it truly seemed could not be answered any way but through political philosophy.

ED: Tell us about your current research. What are you writing about?

MY: I’m currently finishing up a book manuscript on toleration, hope, and the apocalypse. Toleration is frequently seen as the central virtue of modern liberal societies. Toleration is a principled refusal to coercively interfere with ideas or actions we judge to be morally objectionable. As such, toleration is a form of forbearance in the face of disagreement. It’s precious, too – because the practice of toleration enables peace, cooperation, and perhaps even civic friendship despite deep and intractable disagreements.

And yet today, toleration seems to have lost most of its luster. Some view it as too begrudging and judgmental, falling far short of other values like respect or recognition. Others see it as too permissive and accommodating, giving a platform to morally objectionable views. In sum, toleration today is suffering from a crisis of confidence.

My work is aimed at rescuing toleration from its current malaise.

Confident and principled toleration

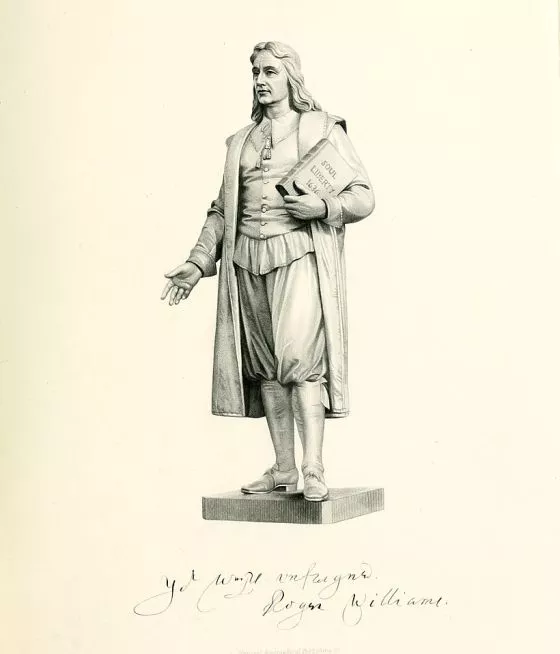

MY: I argue that toleration relies on hope, or a certain sense and certainty that our efforts are not in vain, that evil will not ultimately triumph over good. I show throughout the book how many early modern tolerationist writers drew on apocalyptic theological ideas as a source of hope, tempered by patience. While this may seem counterintuitive, this patient hope allowed thinkers like the early American Roger Williams to sustain their commitment to toleration in the face of grave difficulty. While we may not share in this particular early-modern apocalyptic vision, I argue that if we’d like to maintain confident and principled toleration today, we’d do well to try to cultivate a sense of hope.

ED: What’s your favorite source that you studied throughout your research, and why?

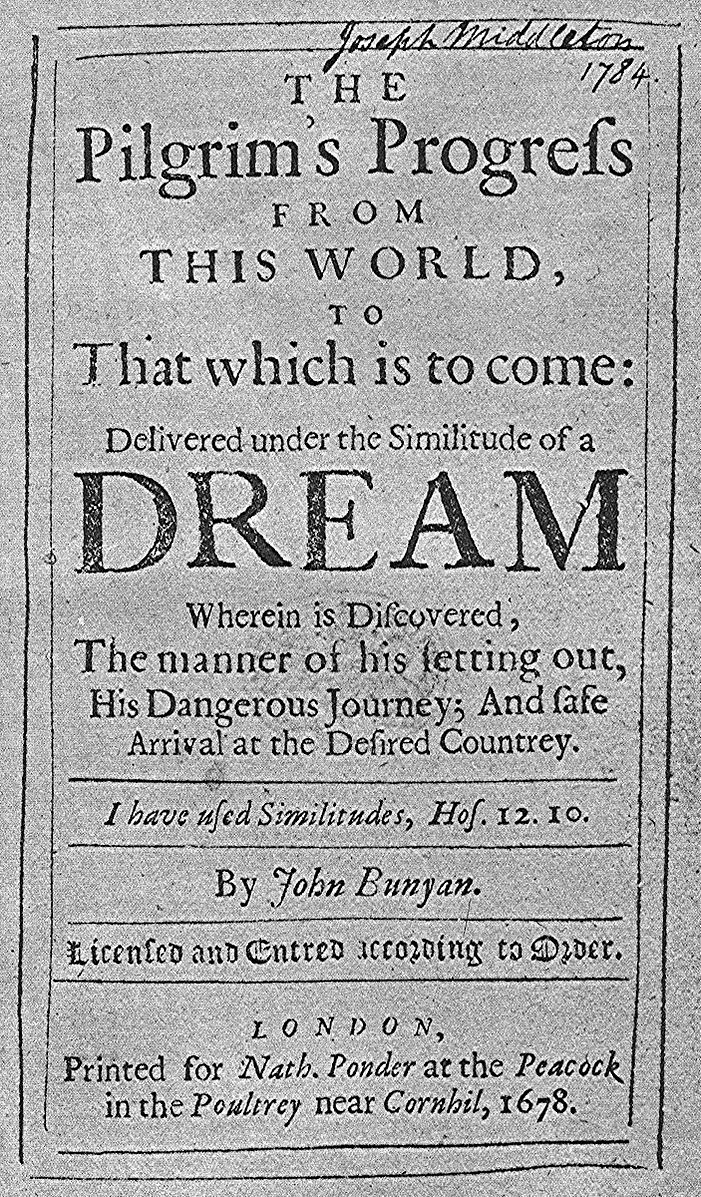

MY: One chapter of my book examines the writings of John Bunyan, a 17th-century non-conformist minister who, while imprisoned for preaching without a license, authored one of the finest allegorical novels ever written: The Pilgrim’s Progress.

I draw on Bunyan’s fiction, theological and pastoral writings, and poetry to show a distinctive approach to toleration that rests in large part on his belief in divine judgment and retribution. In the Social Contract, Jean-Jacques Rousseau writes that “it is impossible to live in peace with those one believes to be damned.” Yet Bunyan shows the exact opposite—that in fact, believing in divine judgment can help us tolerate disagreement. Without divine judgment, toleration seems like allowing evil to persist and go unchecked in the world—a sort of injustice. Yet if there is a just God who will ultimately punish evil, then it excuses us, in the present, of trying to punish them – in other words, true believers can leave retribution to God (“vengeance is mine, I will repay” says the Lord), and instead practice toleration. I find this argument delightfully counterintuitive and provocative, and it’s held my attention for years now.

ED: Why does apocalyptic language remain relevant in the world today?

MY: Look around! Apocalyptic language is ubiquitous. Whether it’s rising tides, economic inequality, nuclear holocaust, global conflict, AI and automation, forest fires in the Amazon, pandemics, even the way we talk about presidential elections, apocalyptic rhetoric is everywhere. And that’s to say nothing of the hundreds of millions, if not billions, of adherents to apocalyptic religious beliefs. In this way, we are not so different from the thinkers I write about, who too lived in apocalyptic times.

Yet I worry that the dominant apocalyptic narratives today are substantially different than the sort of traditional religious apocalypse. The apocalypse, in its classic sense, is an unveiling, a moment of revelation where things formerly hidden become visible. And so the historical thinkers I study found it to be a source of hope and promise amid desperate situations. And yet today “apocalypse” is more synonymous with “catastrophe.”

It seems that our apocalyptic rhetoric in the present may increase the stakes of conflict without offering that sense of hope that sustains toleration and the promise that we can weather difficult seas together.

ED: Explain how you teach your favorite topic to college students.

MY: My favorite courses, or topics within courses, have to do with toleration and civil discourse. As a teacher, a political theorist, and a citizen, I’m entirely committed to helping my students and fellow citizens learn how to live together despite their disagreements. I think this is the single greatest problem in political life. I try to develop practices surrounding civil discourse, free speech, and toleration in every course I teach, but sometimes I get to address this problem head-on (including in cooperation with the Jack Miller Center, where I’ve led seminars for K-12 civics educators and college faculty on how to develop a culture of civil discourse in their classrooms).

In a couple of months here at Elon, I’ll be teaching a short course on “Polarization & Civil Discourse.” We begin with a simple observation: we rarely talk with people who disagree with us on serious political or moral issues, and when we do have those conversations, they seldom seem to go well. Few people think that our state of civil discourse in the United States today is healthy. In this course (which was deeply inspired by my friend and former colleague John Rose), we spent the first few meetings trying to grasp the causes and costs of polarization: Why are we polarized? Why do we respond so poorly, when we are challenged about our beliefs? Why is it so hard for us to own up to being wrong about something? Is there any way to set up our conversations for success? What virtues or practices might we need to develop in order to build and sustain this capacity for conversation, cooperation, and perhaps even friendship across our differences?

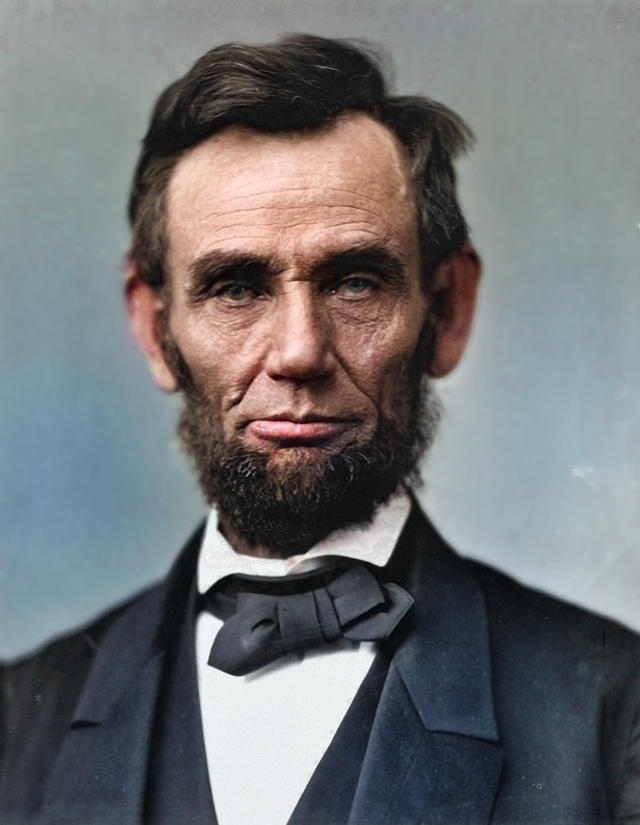

Just like any other skill or virtue, civil discourse requires practice. And so over the remainder of the semester, I sit with students and we practice having the same big, serious conversations about politics that we’re so used to ending disastrously. But we do so with a shared commitment to keeping our conversation going, to listening carefully to each other, to speaking authentically and sincerely, and to prioritizing understanding over scoring cheap points. I’m deeply inspired by Abraham Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address¸ where he says “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies.” Lincoln pleads with the American people to call upon the “better angels of our nature” for help in this fight. My teaching is an attempt to help my students uncover and strengthen the better angels of their nature, for the same goal – because if we are to have hope for the future, I think we must somehow learn to be friends, rather than enemies.

ED: What does your work reveal about the American political tradition?

MY: This fall, I’ve been teaching a course on American political thought, and I’ve been continually struck by the role of hope in the American political tradition. In my work, I argue that toleration relies on hope, but I think that more broadly, the entire success of this political experiment that we call the United States of America rests on a certain hopefulness. I believe there’s a common trope, internationally, about Americans being this deeply optimistic people. And yes, it took a certain optimism to board a small ship and sail across the ocean and dare to suggest that your little colony, starving through its first winters in Massachusetts, would be a “city on a hill.” It took hope for Roger Williams to enshrine the liberty of conscience in the colonial charter for Rhode Island and Providence Plantation. It took a certain optimism to argue, as The Federalist does, that the United States might establish a good government by reason and choice rather than accident and force. It took immense optimism and hope for Frederick Douglass to witness and experience first-hand the immense suffering darkness and misery brought by slavery and yet still believe that there was something salvageable and good about this audacious (if imperfectly applied) idea that all men were created equal. Hope sustained Americans through the Civil War, the Great Depression, and World War II.

Things may seem bad today, but I think it’s incumbent upon us to renounce the cynicism and despair that comes so easily, and to find a way to live in hope.

ED: Thank you for your insights and time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).