An interview with Lorien Foote

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Lorien Foote to discuss her work on the important role played by federal fugitives during the Civil War. Dr. Foote is the Patricia & Bookman Peters Professor in History at Texas A&M University, and is the creator and principal investigator of the Digital Humanities Project “Fugitive Federals,” which visualizes the escape and movement of 3000 Federal prisoners of war during the American Civil War.

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

LF: An illness that derailed my original life plan. As an undergraduate, I majored in Political Science, took Serbo-Croatian as my language, and wanted to work for the State Department. However, a mysterious illness during my junior year in college made me hesitant to travel overseas and unsure about my future. I returned to my hometown of Norman, Oklahoma, to get certified to teach high school while I figured things out. I had to take a graduate history seminar (it was on the Origins of World War I) as part of the certification process, and I loved it more than any class I had ever taken. I realized I wanted to be a historian.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

LF: I specialize in the Civil War and Reconstruction, 19th Century America, and War and Society. I think if I’m honest the movie Glory in 1989 sparked my interest in the Civil War. My military history interests were shaped by my first tenure-track job. The university wanted me to teach the military history class that ROTC needed to teach, and I had no training in that in graduate school. So, I applied for the Summer Seminar in Military History held at West Point and loved it. From that point on, I incorporated military history into my research.

ED: How did you stumble upon the history of the 2,800 Union POWs who escaped Confederate prisons in South Carolina?

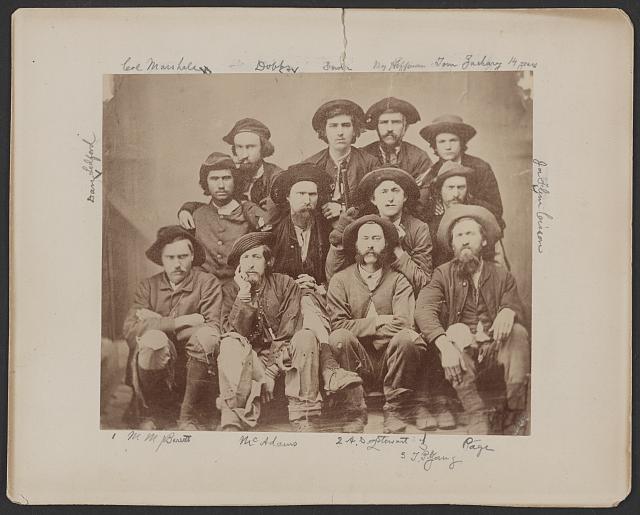

LF: I stumbled on this story during the research for my previous book, The Gentlemen and the Roughs. I was reading the diary of a Union officer from Maine. He was captured and sent to Camp Oglethorpe in Macon, Georgia. Then his diary entries started talking about being transferred to Charleston, and being put into an open field in Columbia, South Carolina, and then escaping, and then having dinners and conversations in enslaved people’s cabins, then running into so many other escaped prisoners that the roads were crowded, and then staying with Unionists in North Carolina … and I thought, “What is going on?!! I’ve never heard of this.” I had to know more.

The escaped and the enslaved

ED: Explain the thesis of your book, The Yankee Plague: Escaped Prisoners and the Collapse of the Confederacy (2016).

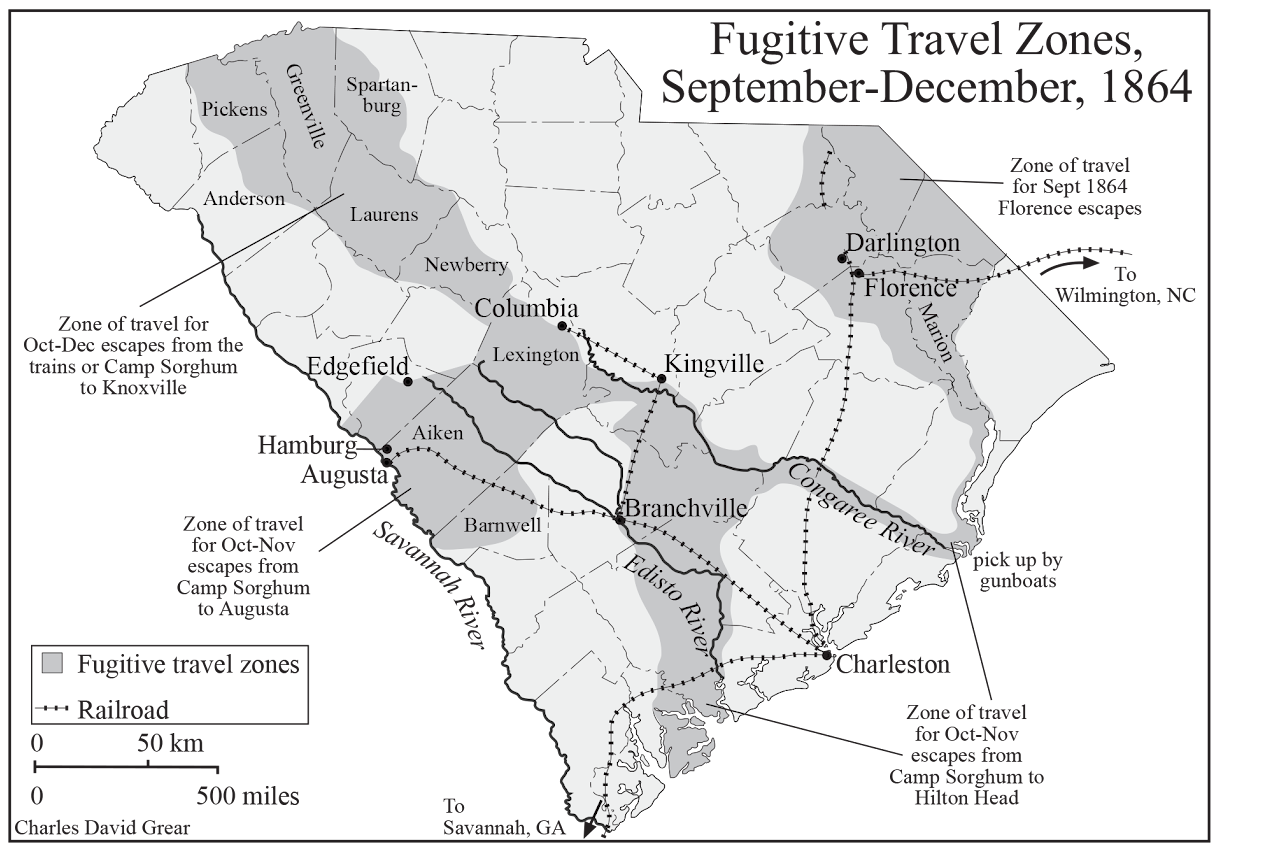

LF: The Yankee Plague tells the story of the mass escape of 2,800 Union prisoners of war from prison camps in South Carolina and North Carolina in the winter of 1864-1865. I use this event to show that the Confederacy in this region collapsed even before Union armies invaded. A number of escaped prisoners communicated to enslaved people that the time had come to escalate and organize their resistance to enslavement and to the Confederacy. I also show that in this region, the absence of white men, due to Confederate conscription, created a crisis of internal security. When faced with deserters, slave rebellions, and mass numbers of escaped prisoners, the state ceased to function in many places.

LF: In North Carolina, the home front collapsed when guerrilla activity made women and children into participants and perpetrators of violence. The movement of thousands of escaped prisoners, and the enlistment of southerners from the region into Union army units in Tennessee that raided into North Carolina, demonstrate that the Confederacy had not established meaningful borders. Finally, I show that Union and Confederate attempts to handle the massive number of POWs in the region interfered with the prosecution of military operations in the final months of the war.

ED: Your work also focuses on the efforts of enslaved people to assist these Union escapees. What effects did their efforts have on the collapse of slavery and the Confederate war effort?

Enslaved people provided escaped prisoners with food, intelligence, guidance across the landscape, and eventually, some organized military force to intercept Confederate pickets.

LF: Their efforts were important for the collapse of slavery in the region. The government of South Carolina had to devote resources to suppressing some organized slave rebellions that occurred in the wake of the mass prisoner escapes. More importantly, because of enslaved people escaping to Union lines, and the consequent resistance of enslavers to Confederate impressment of labor, the Confederacy was not able to get the slave labor that it needed to finish fortifications around Charleston and on the coast.

ED: Did any Union escapees become famous or infamous after the war?

LF: New Jersey fireman J. Madison Drake, who escaped from a train carrying prisoners from Charleston to Columbia, wrote a popular account of his exploits and parlayed that into a minor celebrity for the rest of his life. Two Republican journalists, Junius Henri Browne and Albert D. Richardson, who escaped from Salisbury prison, wrote best-sellers. At one point, their escape party was guided through guerrilla-infested territory by a sixteen-year-old girl, whose exploits were turned into a song by the popular writer Benjamin Russell Hanby. After the war, the murder of Richardson by the abusive husband of the woman he loved led to one of the most notorious trials of the Gilded Age.

ED: Share with us the genesis of the “Fugitive Federals” digital humanities project.

LF: One of the readers of the book manuscript was Stephen Berry, who was pioneering digital projects at the University of Georgia. He pointed out that the database I had compiled from records in the National Archives that contained a list of escaped prisoners with their capture, escape, and arrival points, would yield more insights through ArcGIS mapping and visualizations. I sought out Andrew Fialka, one of the brightest historians I know who had done incredible work mapping guerrilla violence during the Civil War in Missouri and Kentucky, and whose maps had changed how we saw that violence. Andrew agreed to be my project co-director and created initial maps and visualizations. Working with a team at Georgia and geographers at Texas A&M, we developed a prototype website. The project has grown from there. It has become a tool to teach historical research methods and undergraduate students write biographies of the prisoners in the database and these bios are posted on the site and are accessible to researchers.

ED: Describe your favorite primary source that you encountered while researching your work.

LF: Every diary by an escaped prisoner. Because they were unarmed, afraid, and dependent on enslaved people and poor white southerners for aid, and because they were lurking about in the bushes and forests watching and listening to people as they tried to decide whether to approach, they saw and heard things that other people didn’t. My two favorite examples: a conversation between two enslaved people that God was moving as he did in Egypt days, so should they put blood on their doors; an escaped prisoner who ran into an enslaved person who told him where Sherman’s army was in Georgia – the slave was right, and he knew where Sherman was two days before Confederate military officers in the region did.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

LF:

How important it is to have the rule of law in a republic. This was an essential point to the founders: for a republic to thrive, the laws must come from the people, the people must agree to be governed by those laws, and the laws must be applied to all people fairly.

LF: I study a period in American history when there were many people who did not have a say in the making of laws that affected them and when the law was not applied fairly to all people. This damaged the republic and was an important reason that it descended into civil war. It is important to keep moving toward the ideal of the rule of law. This was something that mattered to reformers in the 19th century – it was an essential aspect of political equality. I’ve published a book about courts-martial trials in the Union army and a book about how Americans tried to implement the laws of war during the Civil War. It has been interesting to learn that ordinary Americans, from all walks of life, understood that it was important to have a rule of law regarding how armies could behave in war.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about American history?

LF: I wish everyone knew that we are not more divided now than we ever have been. Journalists, media outlets, and people on social media keep making the claim that we are. But any study of the election of 1800, or the events of 1861, 1919, or 1968, exposes that claim as false. Americans have had many times in our history when politicians demonized opponents, when violence and riots ruled in the streets when people feared that the republic would not last much longer, and when people attacked the very founding principles.

I think it’s important to recognize the deep divisions that have always existed in American society so we can also recognize the values and the commitments that have kept it going through all of that.

ED: Thank you so much for your time and work!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).