An interview with Kelsa Pellettiere

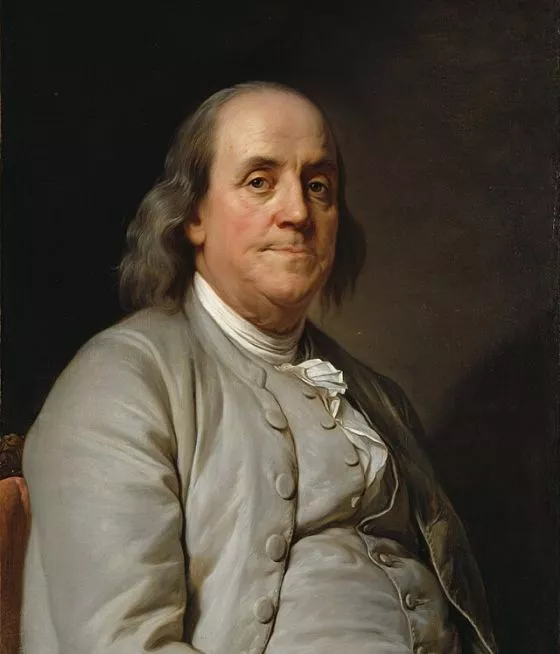

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Kelsa Pellettiere to discuss Benjamin Franklin, Madame Brillon de Jouy, and the politics of personal diplomacy.

The power of personal diplomacy

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

KP: So, my journey with history interesting because I stumbled into it. I always loved history when I was homeschooled as a little kid and when I attended high school it was my best subject. It was interesting and came to me easy, but I never thought I would want to be a historian. I joined the Louisiana National Guard at 17 to pay for college. By the time my contract was up, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life as far as a career. So, one day, when I realized I used up all my electives for history courses, I switched my major to history. One person who particularly encouraged my love of history and determined the projection of both my research and love of teaching was Charles Elliott from Southeastern Louisiana University. He was so enthusiastic, made you really think about why the colonial history of Louisiana was so important to shaping the state today, and he was so supportive by encouraging me to take up space in classroom discussions. He’s the reason I went on to get my MA at Southeastern and pursue my Ph.D. at the University of Mississippi, where I am currently a candidate.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

KP: While my specialty is broadly speaking the American Revolution era, my research explores the fluid relationship between friendship, gender, and honor in early American diplomacy. My dissertation uses Benjamin Franklin as a case study to examine these themes. The way I stumbled into the topic was after taking an independent study with Charles, who I mentioned previously, about the transnational relationship between France and the United States in my MA program. The Louisiana history course I took with him in undergrad left me interested in French history and the colonial era in North America. After reading A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France, and the Birth of America by Stacy Schiff I became fascinated with the idea of personal diplomacy and Franco-American relations, especially since the French Revolution played a crucial role in shaping early US policies both foreign and domestic throughout the early national era.

Franklin seemed to be a culmination of all my favorite research subjects: the colonial era, American Revolution, and France. After reading Stacy Schiff’s book I went on to write my MA thesis on Franklin in France during the revolution. I also study how Franklin’s contemporaries, like John and Abigail Adams, react to Franklin’s French-like behavior during the war. Throughout the war, Franklin’s honor is closely observed, dissected, and attacked due to his behavior in France despite all the grueling effort he put into securing foreign aid, a military alliance, and formal recognition of the United States from one of the most powerful and influential nations in the late-eighteenth century. In many ways, Franklin sacrifices his reputation for his country because he knows that the only way to secure the safety of his nation requires him to perform his duties in a manner that is decidedly un-American (i.e. not protestant).

ED: In your review of Ken Burns’ documentary about Benjamin Franklin, you note the skill with which Burns frames how Franklin addressed the crises of the late colonial era. Tell us how Franklin represented himself and American interests during one of these crises.

KP: Franklin represented colonial interests to the best of his abilities for the most part while he was a colonial agent in England. There were moments when he was clearly disconnected from colonists’ views on certain subjects, but as conflict between the colonies and England continued to build, Franklin became more vocal on behalf of the colonies and urged England to acknowledge their complaints. He played a role in leaking the Hutchinson letters to his friends back in North America which enflamed political passions on both sides. In these letters, the royal governor of Massachusetts called for English liberties being abridged in the colonies and that they should not have full rights compared to those who lived in England. This infuriated the colonists because they had always asserted that they were English men with the rights of Englishmen regardless of where they resided within the British Empire. Following the wake of public outrage from the colonists there were accusations thrown around about who had taken the letters and sent them to North America. This led to two men engaging in a duel with swords when one accused the other of theft of the letters. Duels occurred largely in part to a man’s honor being attacked and dueling was a way for men who were attacked to regain their honor. Thankfully, neither of the men died, but the duel concerned Franklin enough for him to expose himself—quite publicly in the press—as the culprit for leaking the letters knowing full well that this would lead to attacks on his own honor and reputation. Franklin misjudged, however, how the British public in London would react to his confession. While this does enflame passions between England and her colonies, Franklin believed sharing these letters with his compatriots back in North America was the right thing to do because Hutchinson was a public official and the people of Boston deserved to know what these public officials had said with regards to their grievances around representation in Parliament.

ED: Give us a little taste of Franklin’s “party animal” lifestyle abroad, and how that lifestyle informed his diplomatic efforts.

KP: Oh, gosh.

“What didn’t Franklin do?” is a better question.

KP: As the Minister Plenipotentiary to France, Franklin was expected to present himself weekly at Versailles to the French court and then dine with the rest of the visiting diplomats. In this space, Franklin enjoyed all the lively entertainment that only Versailles could provide (especially after dark). It was at these parties where Franklin grew particularly fond of French wine, but he enjoyed the pleasures of French women most of all. While Franklin is popularly remembered for chasing French women–this ranged from simple flirting to sex–his sexual appetites had always been plentiful if we are to believe in his autobiography. In many ways, because of the rumors that have circulated around Franklin during his time, in France, many women who were close to him are often believed to have had sexual relations with the elder American despite the overwhelming about of evidence to contrary.

ED: What were some of the political nuances surrounding Franklin’s friendship with the French thinker Madame Brillon de Jouy?

KP: The Franklin-Brillon friendship is fascinating in terms of understanding how men and women form friendships in the late-eighteenth century. A general understanding of Franklin’s life and his connection to Madame Brillon is that Franklin tried to pursue her, and she rebuffs him—but their relationship not that simple! A significant amount of my research explores how Madame Brillion avoids a sexual relationship with Franklin because she is extremely focused on not damaging her honor and reputation as a woman, which is why she adopts him as her Papa. She is very aware that the standards for propriety differ between men and women and by making Franklin her “father” she can provide a layer of protection for herself. I’ve met a lot of people who are under the impression that sex was a lot more casual in France for both men and women, but Brillon’s letters to Franklin make it glaringly clear that is not the case.

The most important nuanced aspect of their friendship, in my opinion, is that Brillon helps Franklin enter the French social scene as her “plus one” to events before France is ready to recognize the United States publicly.

KP: The French government and French supporters of the Americans could not risk offending the British Ambassador to France, Lord Stormont, because doing so would push France into a war with England before they built up their navy for war. If the French aristocracy showed favor to Franklin, one of the leaders of the American rebellion, by inviting him to prestigious events and showing him favor over the English King’s representative, Lord Stormont, England could have declared war on France before the French fleet was ready. It’s important to note that these events Brillon takes him to are not merely for Franklin to experience the luxuries of the city, because it is in these spaces where Franklin is able to discuss the American war effort with French aristocrats who wish to fund and fight in their war against Great Britain.

ED: Franklin’s views on slavery were complicated to say the least. Did Franklin’s thoughts on enslavement evolve over the course of his life?

KP: Yes, absolutely. Franklin grew up in a society that supported and thrived around the institution of slavery. By default, he participated directly and indirectly in this violent institution both as a slave owner and as a printer who sold ads for slave auctions and descriptions of runaways. Throughout his life, however, he struggled with the idea of enslavement. Unfortunately, it took him towards the end of his life to support ending the institution altogether. Unlike many of his contemporaries, however, Franklin acted while he was alive to try and end the institution when he could no longer ignore the hypocrisy of the United States having fought a revolution for liberty and freedom to hold people in perpetual bondage. One of his finest moments was delivering a petition to end slavery to the United States Congress on behalf of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. Unsurprisingly, his petition was rejected.

Franklin’s suggestion

ED: If Franklin were to teach a course on foreign policy, which texts and writers might appear on his course syllabus?

KP: This is not as easy of a question as it sounds because Franklin did not read books many books specifically on diplomacy before arriving in France. Franklin did consume a great deal of travel literature to understand the culture of other nations. But were he to read specific literature on diplomacy, he would have suggested students to read On the Manner of Negotiating with Princes; on the uses of diplomacy, the choice of ministers and envoys, and the personal qualities necessary for success in missions abroad by Francois de Callères published in 1716. This was essentially a manual to teach a person how to engage in the art of negotiation. It’s been republished over the years by various people but the most amusing version I’ve seen was one reprinted appealing to modern day CEO’s and executives.

ED: What is your next project?

KP: Currently I’m writing my dissertation which is titled “The Politics of Friendship: The Personal Diplomacy of Benjamin Franklin,” which explores the fluid relationship between gender, friendship, and honor in early American diplomacy. It specifically uses Benjamin Franklin’s mission to France during the American Revolution as a vehicle to examine these intertwined themes. My hope is that I can defend sometime in the fall of 2024. I’m also the recuring guest host for the “Historians at the Movies” podcast hosted by Dr. Jason Herbert for the next few weeks where we discuss the new Apple TV miniseries Franklin starring Michael Douglas. It’s been a lot of fun talking with Jason and other notable historians each week since the entire series follows Franklin’s mission to France during the American Revolution, which is the entire scope of my research.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

KP: My research overall has shown me how the American Revolution is a clear moment in time where men and women are associating their individual reputations with the honor and success of their nation during war. I find that quiet fascinating when thinking about how people today in many ways venerate that generation. It brings a different perspective to how people on an individual level interpret the meaning of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” in association with American patriotism.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

KP:

I wish every student learned more about the importance of personal diplomacy and the importance of cultural exchange.

KP: Part of the reason Franklin was so successful in life and in France as a diplomat was because he understood how to connect with people and fostered personal relationships with them. If Franklin had not learned how to treat with the French in their home country, I don’t think Franklin succeeds as well as he does in France to secure American Independence.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).