An interview with Professor Jordan Cash

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Jordan Cash to discuss his book, Adding the Lone Star: John Tyler, Sam Houston, and the Annexation of Texas. Dr. Cash is assistant professor of political theory and constitutional democracy at James Madison College, Michigan State University, and author of The Isolated Presidency.

Nothing new under the Texas sun

ED: What inspired you to become a political scientist?

JC: I came to the study of political science through my interest in history. When I was quite young, my great-grandmother gave me a set of books on presidents and first ladies, and my grandmother gave me a book on the American Revolution soon after that. Those books had quite an effect on me and sparked my interest in history, and specifically in American history. Later on, I became fascinated with ancient history, to the degree that I wanted to become a classicist and study ancient Rome.

When I was in college, I double majored in history and political science and after taking classes in both majors, I realized I could pursue my interest in political history through political science, particularly after taking several classes in political theory and constitutional law. With this realization, when I was looking at graduate schools, I looked at political science programs where I could explore all of those interests. In effect, I became a political scientist because that was the field where I was most able to explore all those areas of study that I was interested in.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

Significant institutions

JC: My specialty is in American politics, particularly American political institutions: Congress, the presidency, and the Supreme Court. I was drawn to the study of institutions because I wanted to examine the intersection between political theory and political practice, and how the theories undergirding the institutions affected the behavior of political actors. As with my general interest in history, I was first interested in presidents, and later became more interested in the courts and constitutional law.

Yet as I began to study history and the American political system, I started to see how significant institutions are not only to American politics generally speaking but also to American political thought. That the function of how our regime is meant to operate is tied into how these institutions are structured to achieve certain functional ends. This is apparent in the presidency both in how presidents often articulate new theoretical and constitutional understandings of our regime—think Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Abraham Lincoln, or Woodrow Wilson—but also in how they act, demonstrating the way the Constitution sets up institutional actors to behave in particular ways. That kind of analysis is really the central core of my research, examining the constitutional logic of the institutions in our system and how that logic orients the behavior of officeholders.

ED: Explain the thesis of your new book, Adding the Lone Star.

JC: In Adding the Lone Star, I seek to uncover the nuances of presidential power through a comparative of two American-style presidents working on the same issue at the same time, but from two different constitutional, institutional, political, and geopolitical positions.

Specifically, I examine how American President John Tyler and Texian President Sam Houston pursued the annexation of Texas to the United States.

In examining these two presidents, I argue that we can better perceive the nuances and conditions which affect how American-style presidents use their constitutional, institutional, and political authority.

More specifically, I contend that we gain three insights into presidential power from this comparison. First, we see the immense control that presidents have over foreign affairs even in the face of daunting external circumstances and pressures.

Second, by including the Texian presidency in the discussion of the American presidency, we can observe how variations in American constitutional practice affect presidential behavior.

Finally, by assessing the different sizes and relative strengths of the two republics, we can better understand the avenues available to American-style executives in responding to diverse geopolitical conditions. Thus, together Tyler and Houston help us see the complexities and possibilities of executive power, while also reminding students and scholars of American politics of how comparative analysis can enable us to better understand variations and subtleties in our constitutional system.

ED: Most Americans might not know much or anything about President John Tyler. Why should Americans know more about him, and what should they know?

Tyler might be the most interesting American president nobody has ever heard of.

JC: Usually if anyone has heard of him it is as the second part of the catchy alliterative campaign rhyme from 1840: “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” the “Tippecanoe” being William Henry Harrison who was the presidential candidate when Tyler ran for the vice presidency. Yet Tyler becomes more interesting once in office because when Harrison dies a month into his term, Tyler becomes the first vice president to become president upon the death of his predecessor, the first “accidental president.” Indeed, his assertion that he became the president upon the death of his predecessor set the precedent that vice presidents would fully assume the office in the event of a presidential vacancy and not merely be an “acting president.” This is a significant constitutional precedent Tyler sets that would later be codified in the Twenty-Fifth Amendment over 120 years later.

But even after becoming president Tyler has major problems. He vetoes a few bills his party supported, so they expel him from the party, making him an anomaly of presidential history: the president without a party. In such a situation one might expect that Tyler would be doomed to failure and that Congress is going to roll over him, but instead, Tyler aggressively asserts the constitutional authority of his office and is able to achieve some of his policy goals, as well as protect the constitutional system from a Congress that seemed poised to unbalance it. In short, despite Tyler’s obscurity, he has a surprisingly rich constitutional legacy and a record of success that belies his difficult political situation.

ED: You compare Tyler and Texian President Sam Houston’s approaches to foreign policy matters throughout your book. What were some of the major differences between their approaches?

JC: The major differences between Tyler and Houston in how they approach foreign policy are driven primarily by their differing institutional circumstances. Tyler is president of a rising great power, so he does not have to worry about any immediate existential threats to the United States. Rather, Tyler’s problems are all domestic. He has no electoral legitimacy as an accidental president, Congress does not like him, and he was expelled from his own party. He is extremely constrained institutionally and is what I term an “isolated president” who only has his constitutional authority to rely on.

The sun of Houston

Houston, by contrast, is immensely popular, the hero of the Texas Revolution who is the overwhelming choice to be president of Texas. Indeed, without political parties in Texas, Houston becomes the sun around which Texas politics revolves. But Texas is a small weak republic at the mercy of its neighbors. Mexico wants to reconquer it, the U.S.—at least for the first few years of Houston’s tenure as president—seems indifferent to it, so Houston must look elsewhere for support. That is the main difference, Tyler is forced to negotiate with his domestic opponents and convince them of annexation, while Houston must develop a grand strategy to weave through the interests of stronger international powers, particular the United States, Mexico, and European powers, particularly Great Britain and France. Indeed, Houston leverages European support to scare the Americans into action, while Tyler has to try and ensure the annexation of Texas from becoming a full-blown sectional crisis between North and South.

With Tyler, I think one of his key characteristics was his resilience.

ED: Did Houston or Tyler possess any character or leadership traits that modern Americans might want to emulate?

JC: He lost all the political supports presidents normally rely on and yet continued to press on and achieved some significant successes. He could have given in to Congress, which would have had substantial ramifications for the relationship between the branches and our constitutional system more broadly. Thus, Tyler’s resilience, his willingness and determination to press forward, I think can be important lessons for modern Americans. Of course, Houston was also extremely resilient. He came back from a personal scandal that saw him resign as governor of Tennessee to then become the president of Texas a few years later. It is an amazing political comeback story.

But Houston I think also demonstrated a high level of strategic thinking and action that is quite impressive given the position Texas was in.

He managed to maneuver Texas through a very difficult and hostile time, and that ability to see the whole picture, to know how other nations would likely react to his moves and anticipate them is demonstrative of Houston’s acute perception and strategic thinking. That ability is an important but often understated part of leadership, to have a goal and to be able to make and follow through on a plan to successfully achieve it. Houston did that despite numerous setbacks and leveraged these other players to act in ways that served his cause. It was an impressive display of grand strategy that not only preserved Texas’s independence, but ultimately secured its annexation.

ED: Give us a few examples of how the politics of slavery influenced the annexation of Texas.

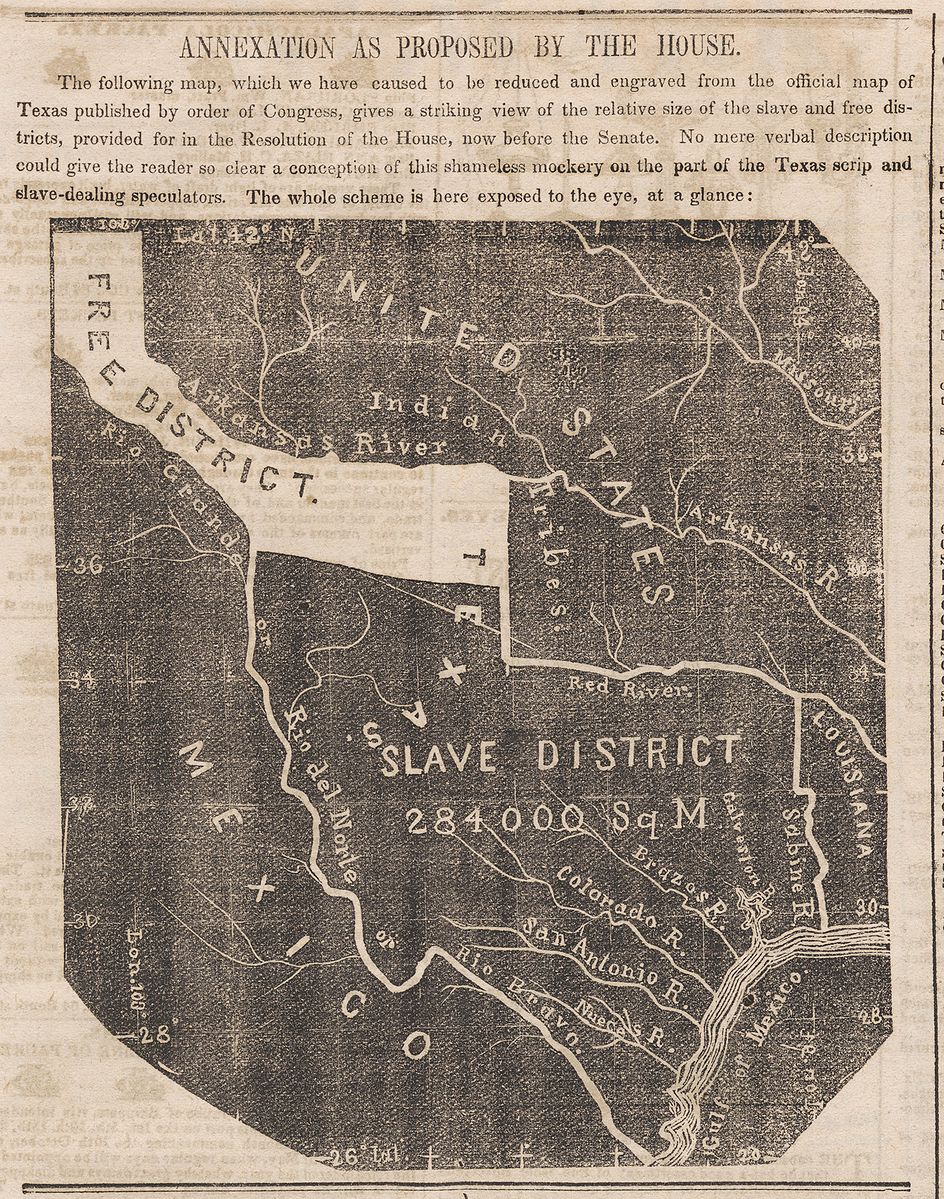

JC: There were a couple ways the politics of slavery influenced the annexation of Texas. First, the Texians—who had slavery—tried to use the prospect of abolition as a way to scare the Americans into acting. Specifically, Houston and his administration cozied up to England—which was known to support global abolition as a matter of policy—and made sure the Americans knew they were doing it, suggesting that they might come under Britain’s sphere of influence and might even abolish slavery. This was unacceptable to many Americans in the South who supported annexation, including members of Tyler’s cabinet, who then pushed Tyler to be more aggressive on annexation.

Second, the South’s interest in annexation meant that many Southern Americans—as well as many Northerners and abolitionists—viewed annexation as a win for the South. This gave Tyler some problems as he continually had to make the argument that annexation would help the nation as a whole. His secretaries of state actually did not help with this. His last secretary of state, John C. Calhoun, made the pro-slavery argument for annexation and even included a pro-slavery letter with the annexation treaty when he sent it to the Senate. This certainly contributed to the initial annexation treaty failing, so Tyler had to find some other way to achieve annexation, which, of course, he eventually did, utilizing the pro-Texas sentiment of James K. Polk’s election victory in the 1844 presidential election to pass a congressional resolution approving annexation.

Once Texas was annexed, it sparked the Mexican-American War which contributed to the debates over slavery in the western territories gained in that war. Figures like the abolitionist Frederick Douglass and former president John Quincy Adams remarked that Texas annexation was a victory for the slave power, and even Ulysses S. Grant in his Memoirspointed to annexation as a conspiracy to create more Southern slave states.

Once Texas was annexed, it sparked the Mexican-American War which contributed to the debates over slavery in the western territories gained in that war. Figures like the abolitionist Frederick Douglass and former president John Quincy Adams remarked that Texas annexation was a victory for the slave power, and even Ulysses S. Grant in his Memoirspointed to annexation as a conspiracy to create more Southern slave states.

ED: When comparing Tyler and Houston’s use of executive power, did you find any commonalities between the two presidents?

JC: While their constitutional and political circumstances were quite different, they used their common powers in similar ways. As their treaty and military powers were constitutionally quite similar, they had a large degree of control over their nations’ foreign policy and they clearly utilized it, often acting unilaterally in pursuit of their policy goals. Indeed, one of the main takeaways from these cases is to reemphasize the primacy of presidential policymaking, particularly in foreign policy. If we broaden out our scope to consider the whole history of American interest in Texas, we can see that, from the beginning, annexation was driven by presidents, Tyler and Houston were simply the ones who finally accomplished it.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

JC: The first thing my research has taught me about our founding principles is that they still matter. The manner in which the Constitution structures and empowers our institutions continues to have an effect on how officeholders use their authority. It is fashionable today to say that the founding principles do not really matter, but these founding principles structure how political actors behave today, and if we do not understand what those principles are, what the political science of the founding was, then we will not be able to truly understand why our politics works in the way that it does.

Historically speaking, I think this book is a good reminder that American history is wonderfully complex and often has permutations we would not expect. Texas began as a Mexican state and had its own Revolution, its own government, even its own founding fathers, but after annexation all of those things became folded into the broader American story. I think we sometimes forget that American history is not just a history of the American people writ large but includes these smaller collections of people in the states, as well as in towns and cities. Local and state history is part of American history, and local and state politics is part of American politics. If we ignore that, or forget to look for it, we miss major parts of our own history and limit our understanding of how our own history and, in political science terms, limit our comprehension of our own politics.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

JC: I wish students would remember how long history is. Not every issue or problem is a new one we have not seen before. On the contrary, many of the major issues we are dealing with we have been seen before in some form or are observable somewhere in history. Few issues are truly unprecedented, and I think history shows that the ancient writer of Ecclesiastes was right: “there is nothing new under the sun.” If we can recognize the kind of issues we have seen before and how they were dealt with then, that can guide us in determining how to address our own problems today. The collective wisdom that history provides can serve as a lesson or a warning, and having that longer perspective of history I think could alleviate much of the anxiety many people have when they look at our contemporary politics. Understanding that we have faced and overcome many serious and significant problems—or that we can learn from our mistakes when we have not overcome certain problems—is invaluable and I believe makes for a much healthier citizenry and a much more useful public discourse.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).