An interview with Jon Lauck

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Jon Lauck to discuss his new book, The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800-1900.

The pure application of the founders’ republican principles

ED: What inspired you to become an American historian?

JL: I was bitten by the history bug very early and I’m not sure I can say why. I have always wanted to know about the origins of things and why events unfolded the way they did. I was also a high school debater, which meant that I was always researching big questions and digging into interpretive debates. I also think that how one views the past shapes the outlook they bring to current affairs so if you don’t have a solid grasp of history your view of the world will be distorted. Getting the facts of American history accurate is critically important.

ED: What led you to write your new book, The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800-1900, and what is your central thesis?

JL: I wrote a book on Dakota Territory titled Prairie Republic because I was teaching a class on South Dakota history and noticed that much of the work on the early years of the state was out-of-date. I noticed that 90% of the non-immigrants who moved into South Dakota were Midwesterners and that caused me to want to explain the DNA of these people. What did it mean that they were moving in from the Midwest? I noticed there wasn’t much work on the Midwest as a region so I dug into the matter and wrote a book on the problem titled The Lost Region: Toward a Revival of Midwestern History (University of Iowa Press, 2013). Well, if there’s no good book on the history of the Midwest I figured I had better write one. That’s where The Good Country(University of Oklahoma Press, 2022) came from.

ED: Where does the Midwest begin?

JL: It begins in Eastern Ohio where the Appalachian plateau ends. That eastern tier of counties in Ohio and those counties along the Ohio River down in the southeast are a borderland. This is all discussed in a new book titled Where East Meets Midwest (Kent State University Press, 2025). By the time you get to Columbus, you are definitely in the Midwest.

The midwest democracy

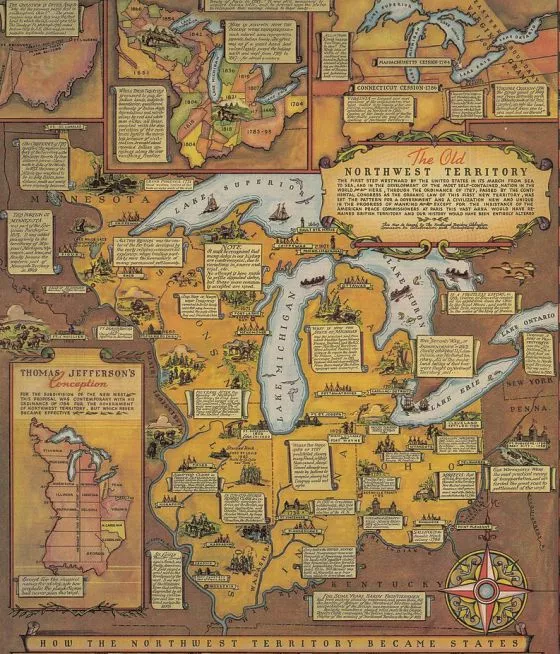

ED: Describe how the Northwest Ordinance influence the early settlement of the Midwest.

JL: It was the magna charta of the Midwest. It set the basic principles for the entire region. It set up highly-democratic self-governing states with broad suffrage rights. It put a premium on education. It guaranteed basic civic rights. It banned slavery. It made the Midwest, in my opinion, the most democratic place in the world for that time.

ED: What types of educational offerings could a typical Midwestern student pursue within the Midwest during the 19th century?

JL: In the Midwest the rates of literacy were sky high. This included the education of African Americans. More African Americans were educated in the Midwest than whites were educated in the American South. Colleges sprung up everywhere—there were many more in the Midwest than other regions.

Education was foundational to civic life in the nineteenth-century Midwest when, by comparison, it was relatively rare in the world at this time.

ED: What role did Native Americans play in the creation of the Midwest?

JL: There was a major continental war fought between native tribes in the 1600s that decisively shaped how the Midwest was peopled. For a long time, the Iroquois drove other tribes West and the early Midwest became a land of refugees from these wars. It is a complicated history of refugees moving and regrouping and trying to find a new home. I recently spent quite a bit of time reading up on this history and it is quite fascinating. If you want a short version, see my new article “Finding the Pre-History of the Midwest: A Note on American Indian Scholarship” in the Spring 2024 issue of the journal South Dakota History.

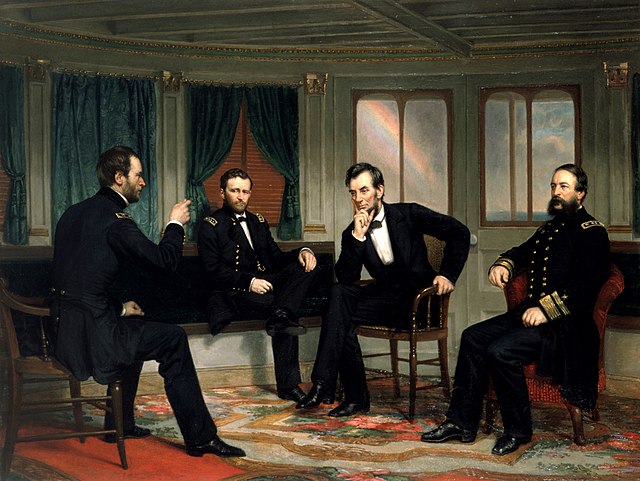

ED: The Midwest can boast that it provided the Union army with over half of its troops over the course of the Civil War. What made Midwesterners so willing to enlist?

JL: They were ardently pro-Union and anti-slavery. Their leaders—Lincoln, Sherman, Grant—were dedicated to preserving the Union and could draw on the profound human and economic resources of the Midwest to make that possible (left, with Rear Admiral David Porter).

ED: Explain how the “deep divide” between the Midwest and the South manifested itself over the course of the 19th century.

JL: There was a definite split between these regions and it steadily grew over time. We used to pay more attention to regions in American history and this has unfortunately fallen out of favor. But the US was a nation of highly distinct regions for a long time and still is, although the distinctions are less stark. The Midwest and the South had completely different economic systems. The South was aristocratic and the Midwest was democratic.

The slave system deeply distorted the South while many churches and civic leaders in the Midwest contributed to an abolitionist movement designed to uproot slavery. When an anti-slavery Midwesterner named Abraham Lincoln was elected president the South seceded and triggered the Civil War.

Without the Midwest, the Civil War likely would have been lost by the North.

ED: You write that the “arc of racial progress in the Midwest bent decidedly upward.” What barriers did African-Americans have to overcome in order to live and thrive in the Midwest?

JL: There were Black Laws and bans on African American voting in the early decades of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois history. It took hard work, but these discriminatory laws were beginning to fall more than a decade before the Civil War. Other northern states such as Wisconsin and Minnesota were more progressive than Ohio and Indiana and so fewer adjustments had to be made. After the Civil War, sweeping civil rights laws abolishing racial discrimination were passed by all the Midwestern states. Remember, this was a century before such laws were implemented in the American South.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

JL: The influence of the founders was very much evident in the early Midwest. It was the founders who wrote the American constitution who also wrote the Northwest Ordinance that governed the Midwest. The republican principles that Gordon Wood and Bernard Bailyn used to chronicle in their work went into full effect in the new Midwest where the people did not have to make concessions to Southerners.

The Midwest is the pure application of the founders’ republican principles.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

JL: It’s complicated. It’s not all one thing. If you see people trying to impose sweeping narratives or theories on the past they are going to stumble. The story is complex. American history differs greatly by region and particular place and because of certain individuals. It’s important that you learn the details because if you don’t you’ll be forced to live with what others assert American history to be.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).