An interview with Jeffery Tyler Syck

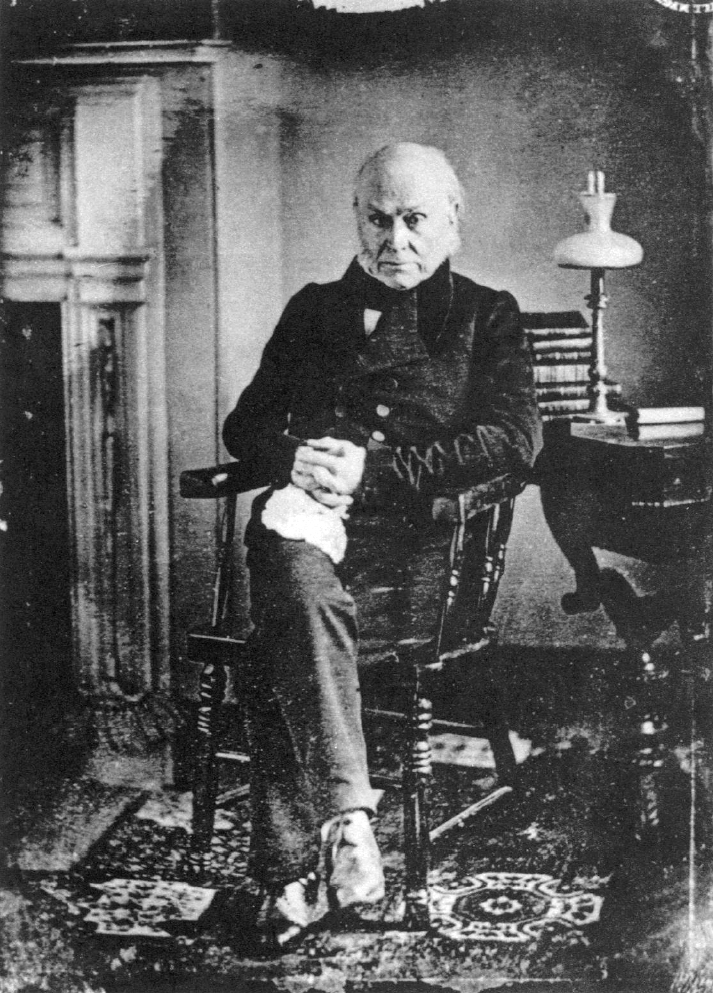

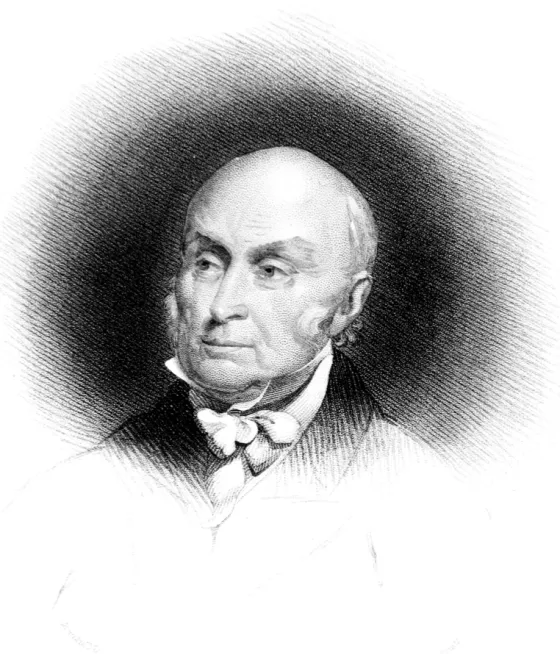

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Jeffery Tyler Syck to discuss his work on John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, and whether the United States is a republic, a democracy, or both.

Recommitting ourselves to the principles of the founding

ED: Do you consider yourself a historian who studies political theory or a political theorist who studies history?

JTS: This is an oddly hard question for me. In undergrad, I double majored in politics and history, as a scholar my research has always blended the two, and now as a professor I teach both. So the two fields have been tightly linked in my mind for as long as I can remember. In the final analysis though, I would say a political theorist who studies history. Most of my research has previously involved studying how big ideas like equality and virtue interact with our political institutions – how a changing definition of freedom might reshape slave policy for instance. That is what political science is supposed to be all about when it can manage to leave all the number crunching behind. Though I will add that I am increasingly attracted to what Fredrich Nietzsche called “monumental history” – the study of great deeds and ideas aimed at inspiring future generations. So I may try to dabble in that a bit more in the future.

ED: Can you tell me the moment that you were drawn into the orbit of John Quincy Adams?

JTS: In my second year of graduate school, I was preparing for my comprehensive exams and reading David Greenstone’s book The Lincoln Persuasion. There is a really interesting section of that brilliant book on the political thought of John Quincy Adams. Now I will admit that until that moment I always saw John Quincy Adams as his father’s less impressive intellectual understudy. But I found reading Greenstone that I was completely wrong – John Quincy Adams is a unique and complex thinker who diverges from his father in fascinating ways. So I dived into Adams myself – reading everything by him I could get my hands on. My initial impression was confirmed the more I read. John Quincy Adams is one of the noblest and most thoughtful statesmen in American history. I do not think I have ever encountered another American who so brilliantly combines the very best of humanity’s conservative and progressive instincts.

ED: What is the thesis of your book project,The Untold Origins of American Democracy?

JTS: There is a pretty big debate among members of the American public about whether the United States is a republic or a democracy. My book project seeks to answer that question and the conclusion I came to after years of study is that we are sort of both. The founding fathers tried to create a republic – that like all republics would foster political consensus and protect the rights of the people. The problem was that many Americans at the time did not feel that the republican government gave proper scope and authority to the will of the people. So very quickly after the founding our regime began to democratize. That is where things are today – in attitude I would say we are mostly a democracy but we have a lot of republican institutions and impulses. Typically, this blend is a very good thing for us and I think we should maintain the balance as best we can.

I pinpoint America’s ongoing transformation into a democracy to the presidency of Andrew Jackson and his republican detractors – John Quincy Adams and John C. Calhoun. These three men, more than any other, are responsible for the wonderfully hybrid form of regime we now have.

An American Cicero

ED: Give us a little background on how John Quincy Adams made the transition from President Adams to Congressman Adams.

JTS: After he lost to Andrew Jackson in the 1828 presidential election, John Quincy Adams was understandably pretty crushed. He felt that like his hero Cicero, he had failed to save the republic from a dangerous demagogue who would inevitably destroy our freedoms. So, like Cicero, Adams planned to retreat to the countryside and write philosophy. He did end up writing quite a bit of philosophy but he was also approached to run for Congress and agreed – over the serious objections of his family who thought it demeaning for a former president to occupy a lower office.

Despite his family’s concerns, Adams proved to be a remarkably good congressman.

JTS: Without anything left to prove to the world, he simply followed the dictates of his own conscience – churning out a long philosophic speech turned essay every couple of years, he also launched a crusade against slavery that earned him the undying respect of America’s slave community. All while founding the Smithsonian Institute and leading the charge for the nation’s first funding for scientific research. In many respects, he was a far better congressman than president and I think the last chapter of his career is probably the greatest.

ED: Which essay by Adams is your favorite and why?

JTS: My favorite essay by Adams is a long reflection he delivered on the Social Compact while in Congress. It is where the true uniqueness of his political thought is most obvious. Adams is not the first person to write on the idea of a social contract, and he pays a lot of attention to the ideas of John Locke, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and Hobbes. But at the end of the day, Adams does not really agree with any of them.

For Adams, the social contract makes the most sense as a historical phenomenon.

Unlike all the other social contract theorists, Adams thinks that the idea of free government needs to be based on the history of freedom instead of an abstract conception of it.

JTS: So throughout the essay, Adams lays out in moving detail how self-government came to the United States. The whole piece is an interesting reflection on how history can be deployed to defend and promote philosophic ideas. The essay also just serves as a nice way to think about the development of natural rights philosophy in practice.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

JTS: I think the most important thing that I have learned is that the American founding is in many ways still ongoing. We are the first country in human history dedicated to the idea that all men are created equal and that the government consequently exists to protect our rights. That goalpost is a foundational principle that never changes, it’s based on a simple fact of human nature. However, how we accomplish that goal will have to change subtly as time goes on. Our founding fathers did not think they had all the answers and they did not – none of us do. That is why we have the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. In short, the preservation of our noblest ideas will require some level of evolution over time. We must recommit ourselves to the principles of the founding in each new generation and find where we are failing to live up to “the last, best, hope of the earth.”

ED: What’s one thing you wish every student knew about the American political tradition?

JTS: When I went into teaching American politics, I thought the hardest thing would be explaining some big theoretical concept like “all men are created equal” to young people. What I found is that the biggest problem that faces so many young people in their political education is that they feel so divorced from politics itself. It’s not that they hate their country or its principles, they just cannot fathom that they have a place in its politics and thus think this is all not that important to them. So the one thing I have just lead with in my classes and that I wish everyone knew about our history is that they are themselves part of the American political tradition. The United States is founded, partially, on the idea that we are not ruled by some distant monarch across the seas.

We here in the United States rule ourselves. That means each of us – students and professors alike – are called upon to understand, defend, and refine our political tradition.

JTS: The founding fathers left us with a big task. A hard task. But I think it’s a very beautiful thing and I wish all students could see that.

ED: Fascinating insights, thank you for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).