An interview with Jason Canon

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC network member Jason Canon to discuss his work on empathy, democracy, and early modern political thought. Mr. Canon is a doctoral candidate at the University of Cambridge.

ED: What inspired you to become a political theorist?

JC: I’m told that when asked as a child what I wanted to be when I grew up, my earliest response was “a fire hydrant”. I’d like to think that I’ve made better career choices since, though with some loss in job security.

Through college, I planned on a career in political office. Two discoveries changed that plan: the first was an internship with a U.S. Senator, in which I discovered how little of their life I wanted for my own. The second was a remark by Friedrich Hayek that one could make a greater contribution to others by working on ideas rather than the business of politics.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

JC: My work focuses on political sentiments: how we feel about politics and how politics makes us feel. This remains a remarkably understudied area of political science, particularly in exploring how emotions decide how we vote. Why are fear and anger such potent political forces? How can empathy create understanding when we disagree? These and related questions were first formulated during the Enlightenment, and so that’s where I’ve begun my research.

I hadn’t paid much attention to sentiment until 2016. First, the Brexit vote and then the November election showed me that we’re far from appreciating its import. The election was on November 8; I began writing on these questions the day after.

ED: Tell us a little bit about your most recent project.

JC: If there’s one thing that we could use more these days, it’s understanding. Empathy — our ability to feel what we think someone else feels — drives much of how we understand one another, but we lack any general model of how it works in politics. Or, for that matter, how politics shapes empathy. Which regimes are more or less conducive to this kind of emotional understanding? Do some institutions harness it better than others? We simply don’t know.

Sympathy and empathy

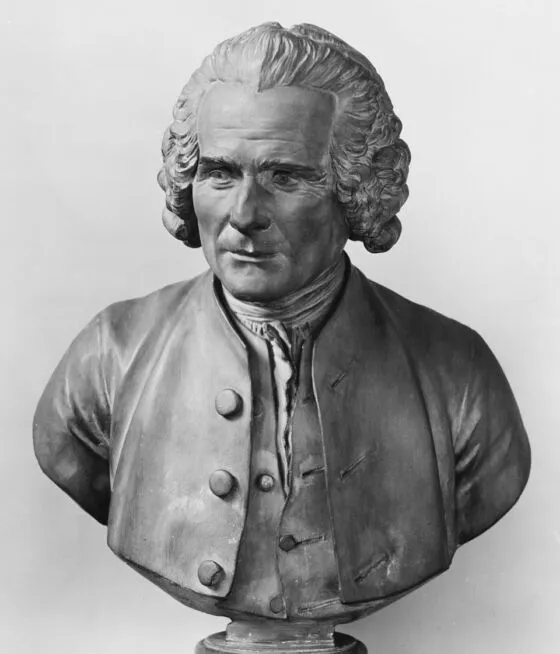

JC: Our poor understanding of empathy isn’t entirely our fault: political science is rightly more concerned with conflict than concord, and we didn’t even have the word “empathy” until 1908. But prior to that, centuries of political theorists had been thinking about related notions of “sympathy”, and so my dissertation returns to some of the most important of these — especially David Hume, Adam Smith, Jean-Jacques Rousseau [right], and Sophie de Grouchy — to ask what we can learn from their accounts, and what contemporary psychology and philosophy (which have made far more progress in recent decades) can reveal about what they got right and what they missed.

ED: What was your favorite research rabbit hole, and why?

JC: It has almost nothing to do with my dissertation, but I’m forever fascinated by debates on the nature of freedom. There are almost as many theories of freedom as there are political theorists, all emphasizing one or another aspect: freedom from domination, from wrongful interference, from fear.

I’m drawn to this debate because it’s one that cannot be decisively answered, and yet each attempt at an answer reveals something essential about what it means to be free at this moment, as this person, in this polity. It’s a conversation that must continue if we hope to preserve our system of self-government.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

JC: It’s helped me appreciate how the Founders saw themselves as participating in the central debates of the Enlightenment. This has been known to generations of scholars, of course, but I continue to be impressed by the transatlantic traffic in revolutionary ideas. Hume’s importance to James Madison, Smith’s importance to Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Paine’s collaboration with Grouchy in France —

America’s story can’t be told without the story of the Enlightenment, in much the same way that we miss something crucial about the Enlightenment if we overlook the emancipatory possibilities opened by the American experiment.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about American history?

JC: The founding generation’s spirit of imagination and innovation remains available to us still. They believed that humanity could design ways of channeling passion and self-interest into a more peaceful, more prosperous politics. History proved them right. But we’ve not only forgotten many of their conclusions; we’ve lost the ambition and the hope that led them there.

Jack Miller Center scholars (in their different ways, I think here of Gordon Wood and Danielle Allen) have done so much over the years to remind us that America’s experiment — always imperfect, forever unfinished — remains a radical one.

Our current politics look bleak largely because we’ve forgotten this.

Across the world’s liberal democracies, people are wondering whether what we’ve had is the best that things will ever get. America’s story proves otherwise.

ED: Excellent, thank you for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).