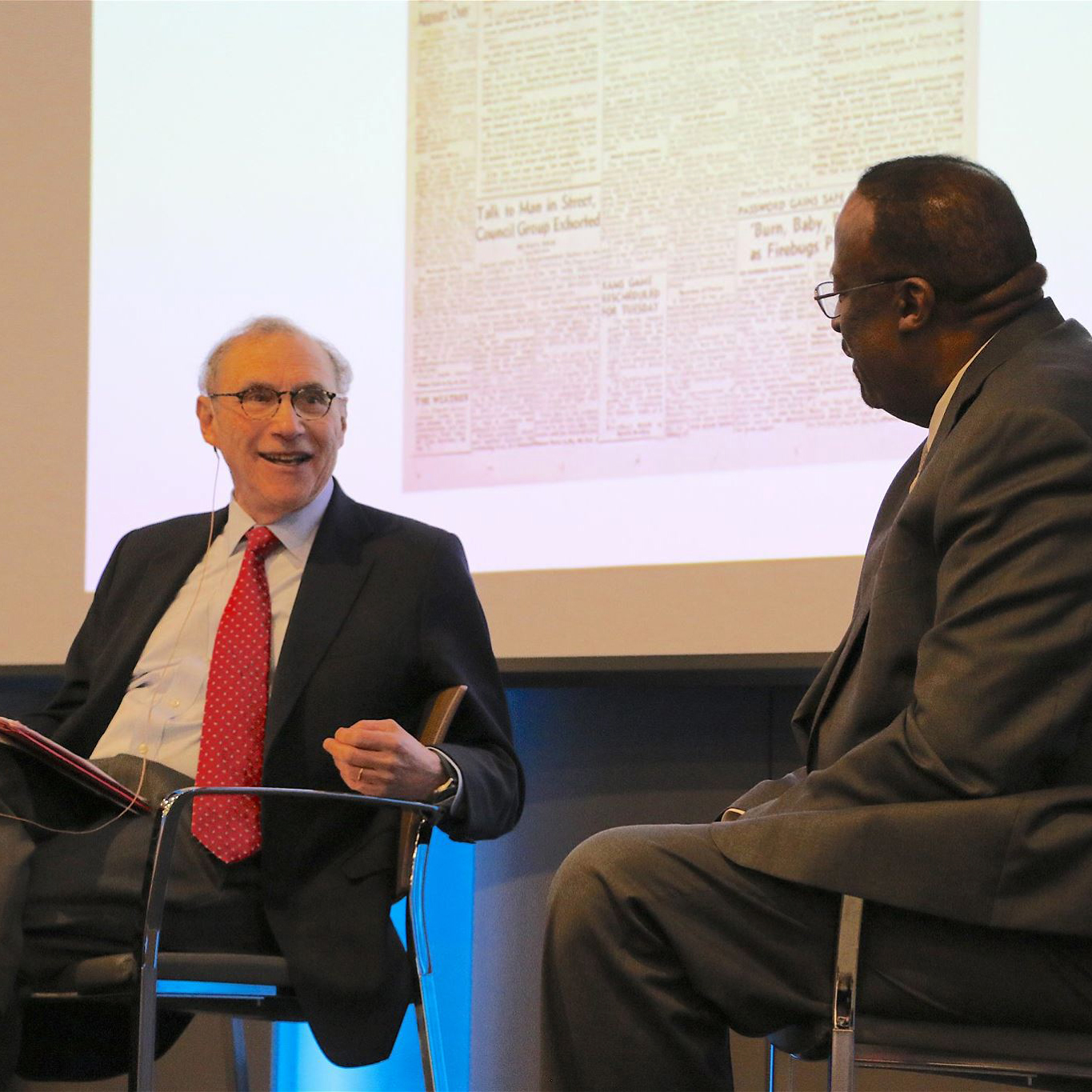

An interview with Gene Dattel

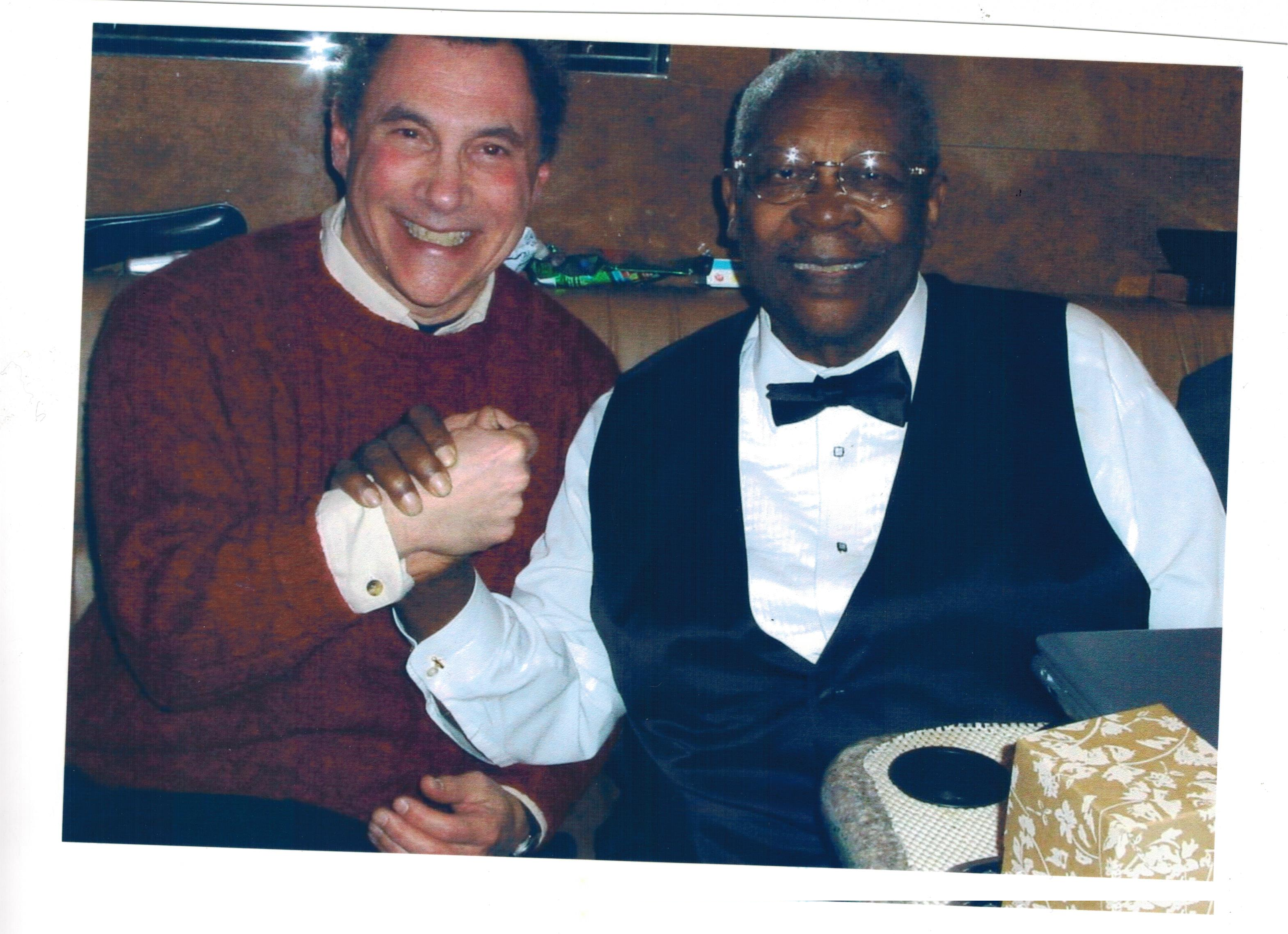

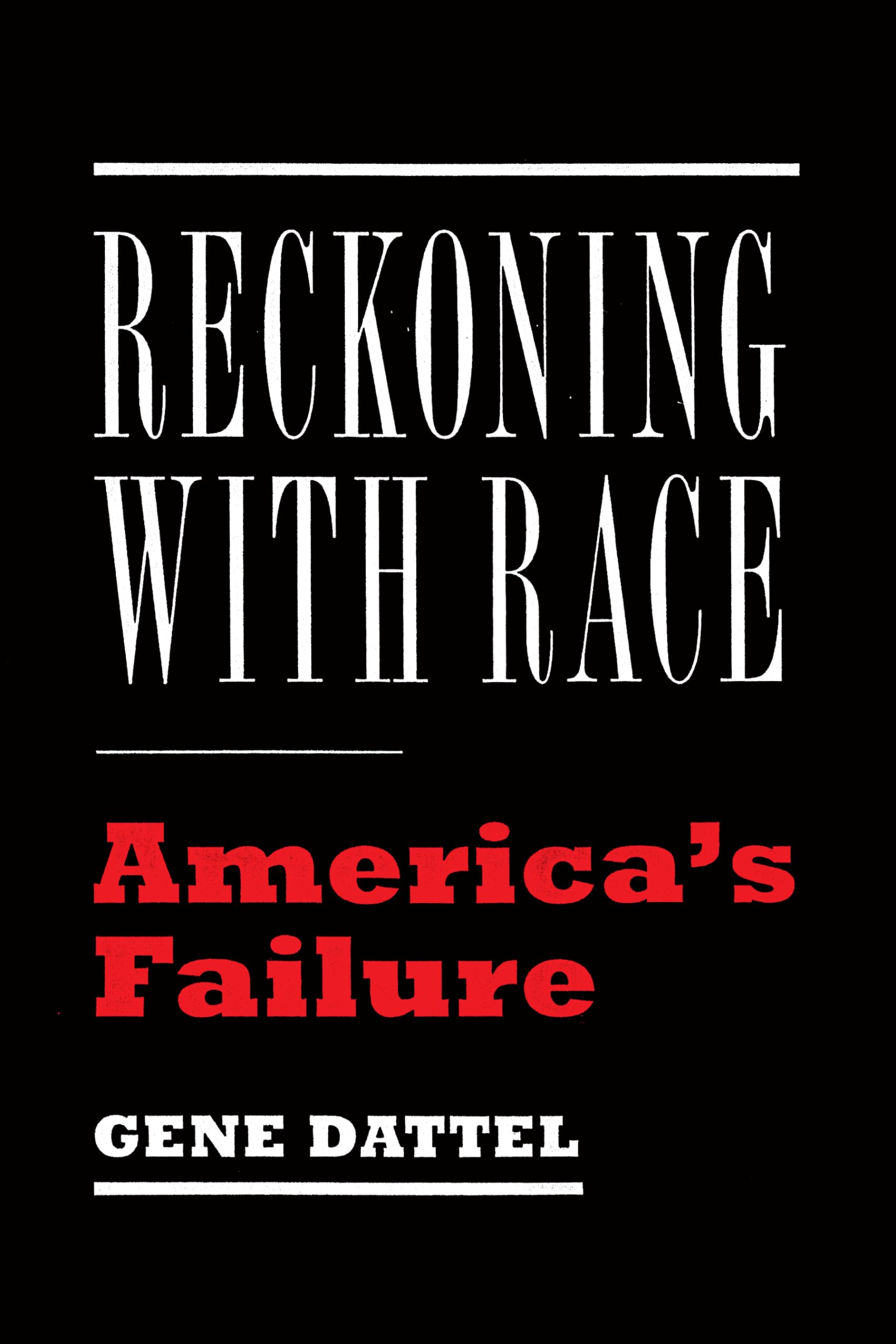

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Gene Dattel to discuss his work on ethnicity and race, economic and cultural history, and the rich exploration of the American experiment. Mr. Dattel has a B.A. from Yale and a J.D. from Vanderbilt University Law School. He then embarked on a twenty-year career in finance as a managing director at Salomon Bros. and Morgan Stanley. He lived overseas for fifteen years in London, Hong Kong and Tokyo. He has served as an advisor to the Pentagon, major financial institutions, and cultural institutions from the New York Historical Society to the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum. He is a Fellow at Yale’s Berkley College and formerly on the advisory board of the B.B. King Museum. His first book, The Sun that Never Rose, presciently outlined Japan’s long-term structural economic problems when conventional wisdom predicted an unassailable economic juggernaut. In addition, he has written Cotton and Race in the Making of America and Reckoning with Race.

ED: Why did you become an American historian?

GD: My serious interest in American history began my sophomore year at Yale (1963) when I took an extraordinary seminar, a survey course in American history taught by Professor Robin Winks who would become a giant in his field. James Meredith integrated the University of Mississippi when I entered Yale. The attendant violence caused classmates to question and criticize me, the only Yale student in my class from a majority Black area, the Mississippi Delta. Mr. Winks recognized my concern and created a private non-credit tutorial for me concerning economic history, racial history, and colonial nationalism during the course. I was hooked for life.

Over the years, I have found that historical analysis is critical in terms of context, complexity, and methodology for understanding issues and events in a variety of areas. The ability to discern patterns via history has been key to my intellectual and professional journey both domestically and in my fifteen years abroad. History, for me, is humanizing. Plus, and most importantly, I am continually captivated and fascinated by historical probing, detective work, and synthesizing.

My books and articles are historically based. Whether Japanese culture, the role of cotton in America, race, or financial history my approach has been that of an historian.

Perhaps, most gratifying, my mentor Robin Winks, early on said, “You think like a historian.”

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

GD: My nine-year sojourn in Japan in the 1980s was the catalyst for my pursuing a multifaceted approach – economic, cultural, and experiential – to history. Japan was feared as an economic threat to America. As such, it was the first non-white, non-Western nation to challenge America (and the West) economically. Because of my extensive contact with private-sector Japanese financial institutions and the Japanese government, I immediately realized that Japan’s financial institutions, as opposed to its manufacturing sector, were dysfunctional and would create a serious structural problem for the country’s growth. My analysis was cultural and historical as well as economic and experiential. I became obsessed with the misunderstanding of Japan’s financial power and wrote a book, The Sun that Never Rose based on the cultural and historical derivation of Japan’s financial institution.

After my Japan book, I turned my attention to America with Cotton and Race in the Making of America which describes the fateful intersection of the global power of cotton to the African American experience. I highlighted racial attitudes in both the North and the South, rather than concentrating on the South. I delved further into arguably America’s most difficult and complex social problem in Reckoning with Race: America’s Failure.

GD: Currently, I am pursuing global racial and ethnic separatism through historical examples with comparisons to America. This project began with my college seminar (1965) “Colonial Nationalism.” Again, my travels – especially during my fifteen years living abroad – provided an opportunity to research and investigate the post-independent path of former colonies and the impact and influence on today’s world and, as C. Vann Woodward wrote in 1960, the “reinterpretation” of Western history.

ED: Do you consider yourself a cultural historian who writes on economics or an economic historian who writes on culture?

GD: As a practitioner in the world of economics, I write about the cultural derivation of finance. So, I am a blend of economic and cultural historians because the linkage is direct. Culture includes ethnic, racial, and historical characteristics. Culture in turn determines the values that permeate each country’s history and its economic, educational, familial, institutional, and behavioral ecosystem. Finance is critical to the proper long-term functioning of a society. Market structure, regulatory, central planning, and judicial environment differ from country to country.

A country’s culture also determines the way different ethnic and racial groups are either separated from or integrated into a society. Concessions to assimilation, in my judgment, are necessary to create social cohesion for a viable path to the economic mainstream.Culture can be adaptive depending on circumstances.

At times it is useful to show the artistic reflection of a country’s economic structure. For example, I have given presentations on “King Cotton: The Art and the Power.”

ED: Describe the main argument of your book, Cotton and Race in the Making of America.

GD: The story of cotton in America is a dramatic economic tale whose fundamental importance in the nation’s history has generally been underappreciated. Slave-produced cotton was shockingly important to the destiny of the United States; it almost destroyed the nation. The Founding Fathers allowed race-based slavery, cotton’s eventual labor pool, to exist at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 because they thought it to be already receding. They were blindsided by the economic tornado that was cotton. Cotton became America’s leading export between 1803 and 1937. No commodity, industrial, or technical product will ever match this reign. Black Americans were fundamentally linked to cotton for sixty years as slaves and for one hundred years after emancipation.

Slave-produced cotton caused the American Civil War and formed the Confederate strategy to win the war. I was convinced that I could describe and analyze cotton’s role before, during, and after the Civil War from the neglected perspective of a financial market participant who was well-grounded in American history.

The power of cotton was analogous to that of oil in the twentieth and twenty-first century.

GD: It was imperative to incorporate the racial experience of free Blacks in the North into the story of Black America. Too often historians exclude race in the North and dwell exclusively on the South, the perennial scapegoat for America’s continuing racial dilemma. The treatment of and attitude toward Blacks in the antebellum North was an important guide to what happened after emancipation.

A complete, nuanced, objective story of the linkage of race-based slavery to cotton over the period of cotton’s ascendancy is essential to our understanding of our most difficult historical social problem. My account deals frankly and directly with the dueling narratives of both the right and left political spectrum.

ED: What made the Mississippi Delta an exceptional hotbed of blues activity?

GD: The Delta provided the appropriate mix, time, and place for the blues to blossom as a distinctive American genre of music. Cotton, the “indispensable product”- produced communities of emancipated Delta Blacks imbued with church music, a social environment, multiple themes conducive to music, proximity to other Black groups in a rural setting, and an abundance of experimentation – provided the background which spawned the music genre. Simultaneously, blues arose in several cotton states, among whom were Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, but the Yazoo Mississippi Delta was the Cotton Kingdom with an exceptionally pronounced depth of the ingredients necessary for music germination. The blues story is well told through the interpretive markers on the Mississippi Blues Trail.

Delta towns, linked by rail, crude roads, and culture, allowed individual musicians to interact throughout the region. The proximity to Memphis and the Illinois Central Railroad connected the Delta to New Orleans and Chicago and allowed the blues to travel to other Black communities and, later to the world and other music genres. (British Invasion rock bands were heavily influenced by blues music.) Led Zeppelin vocalist Robert Plant during a visit to bluesman Robert Johnson’s grave credited Johnson with helping launch his musical career. Two songs on Zeppelin’s first album were Robert Johnson’s songs. Fusion occurred. A London concert featured the London Gospel Choir, Eric Clapton, and Luciano Pavarotti performing together.

Cross-fertilization was possible because of the network of cotton farms and nearby towns with accessible proximity to each other.

ED: Tell us about the research endowments and other exciting projects you are facilitating at Yale University.

GD: For the last nine years, my wife, Licia Hahn, and I have been sponsoring, organizing, and moderating a discussion/mentoring/topical seminar for Yale undergraduates. This was started at one of the residential colleges, Berkeley College, at the behest of Professor Marvin Chun who became dean of Yale College. It covers a multitude of topics of student interest.

I have also sponsored and funded fellowships for Yale students to do projects – oral histories of elderly Black women in Mound Bayou, MS, an all-Black town, and research (the blues music genre– in the Mississippi Delta).

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

GD: Over the years beginning with a course in the American colonial period taught by Edmund S. Morgan in college through subsequent research, I have become profoundly impacted by America’s founding principles. The founders – grounded in classical political theory, fully conversant in the history of governments, blessed with practical knowledge of the affairs of men, cognizant of the foibles of human nature, and with a vision of the future – created a society unique in world history. The nation that they created would be stable and capable of adjusting to a dynamic environment.

The goal of individual freedom, for them, required a government to be constructed with a system of checks and balances designed to avoid the pitfalls of a purely democratic system. They had studied the past and knew what could go wrong.

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 forged a compromise among various diverse interests of states with commercial, size, geographical, political, and historical differences. The result was a constitutional republic that became not only the envy of the world but also the leader of Western Civilization.

I have deep reverence for the founding fathers and the principles which guided them. I return to the contributions of individuals, the Federalist Papers, the assimilation process deliberately installed for a growing land mass and massive immigration, entrepreneurship exemplified by Benjamin Franklin and his American progeny, a judicial system that embodied a corrective mechanism unparalleled in world history, the legacy of British institutions, and a continuity which overcame diversity and challenges from generation to generation. The Founding Fathers did not envision a utopia, but rather a society well-designed for reality and human nature.

My perception of the founding principles was further reinforced by the fifteen years in which I lived abroad in different cultures and my professional encounters.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history

GD: In today’s world of ethnic and racial separatism, it is imperative to understand America’s natural process, unique in world history, of assimilating its diverse population. Millions of immigrants were successfully absorbed into this society.

Concessions to assimilation best describes America’s absorption capacity, the transformation of ethnic and racial groups, and the organic manner in which this takes place. The result allows for cultural heritage to be preserved and social cohesion to underpin a functioning nation while allowing cultural heritage to be preserved. A national identity was/is formed.

GD: Every student needs to know the history of immigration, the attitude of the founders towards integration, religious tolerance, and the practical issues of entering the economic, social, and political mainstream. Students can best appreciate this aspect of American exceptionalism by comparing the experience of other countries. Nations plagued with ethnic and racial separatism cannot function properly. Examples abound.

Currently, assimilation is a loaded word. The academy and the media disdain and reject America’s historical metaphor “the melting pot.” The richness and ideals provided by Crevecoeur and Israel Zangwell are lost. Instead, they prefer “mosaic” (which is brittle, and not akin to the strength of an alloy) and “salad” (which lacks meaning) and a series of rebranding attempts – acculturation, amalgamation, pluralism (which explains nothing except that there are different groups) and now (extreme) multicultural (which sounds positive, but in the current state is anything but positive). All avoid clarity, history, and political identity groups result. Universities exemplify, cultivate, and reinforce the separatism now embedded in our society.

The story is rich in its exploration of the American character, norms, and a path of unity in a world of ethnic and racial separatism. There is an obligation to include the Black America and American Indian experience frankly, without neglecting the validity of American exceptionalism

(Runner-up candidates for students would be 1) the American Free Market ecosystem and 2) the importance and enduring relevance of American federalism.)

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).