An interview with Dennis Hale and Marc Landy

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC faculty partners Dennis Hale and Marc Landy to discuss their new book, Keeping the Republic: A Defense of American Constitutionalism. Both Dr. Hale and Dr. Landy teach political science at Boston College.

People want to live in America…and it’s not because of the weather

ED: What inspired you two to become scholars?

ML: As a kid, I loved both sports and politics and aspired to be a sports writer. From the sports pages of The New York Post, curiosity led me to the editorial pages. Murray Kempton made politics seem even more interesting than sports and far more complex. So much for sports writing. At Oberlin, Wilson Carey McWilliams’ brilliance, wisdom, friendship, and passionate commitment to learning brought out the scholar in me. At Harvard, James Q. Wilson’s razor-sharp mind enhanced my ability to think analytically. Sam Beer showed me that a scholar could be grounded in the political world. The depth of my friendship with BC colleagues Christopher Bruell, Robert Faulkner, and Dennis Hale has kept my love of ideas alive even as I have grown older.

DH: I had originally planned on becoming a journalist, and was writing book reviews and articles for a number of periodicals, especially Commonweal. At the same time, I was enrolled in the doctoral program at the City University of New York and was a teaching assistant at Brooklyn College. So I was torn in two directions. But my heart was really with the scholarship, and I finished a dissertation on American Political Science and the Meaning of Citizenship and earned my doctorate. At just around this time Marc Landy alerted me to an opening in the Political Science Department at Boston College (where he was already teaching); I interviewed, was hired, and have been at BC ever since.

ED: Briefly tell us the main theses and themes of your book, Keeping the Republic: A Defense of American Constitutionalism.

ML/DH: Keeping the Republic is a defense of the American constitutional order, and a response to its critics, including those who are estranged from the very idea of a fixed constitution. The central argument of the book is that the Constitution provides for a free government because it places effective limits on the exercise of power. This is an essential ingredient of any good government—even one that aims to be a popular government. That the people should rule is a given among Republicans; that the people can do anything they want is a proposition that no sane person could believe.

Thus, the limits that the Constitution places on American political life are not a problem, but a solution to a problem.

ED: Why do some Americans believe that the Constitution is “broken”?

ML/DH: They believe the Constitution is broken because of the insurmountable obstacles that it thwarts the will of a national majority, protects the economic elite, does not accord a sufficient role for disinterested expertise in government, and is incapable of stemming the decline of trust in government. The Senate is undemocratic because the small states get as much representation as the large ones. The Electoral College is undemocratic because it makes it possible to thwart the will of the national majority. Federalism is undemocratic because the policies of individual states can thwart the national majority. The judiciary exercises undo autonomous power.

The Constitution places undo emphasis on property rights and insufficient attention to regulation of business, thus, economically disenfranchising the majority and enabling major corporations to exert undo economic and political power. The Constitution does not sufficiently control the role of money in elections and the role of industry lobbying. The Bill of Rights does not declare enough rights.

It is too focused on negative rights – what the national government cannot do – and omits rights to a clean environment, an explicit right to privacy, necessary to protect abortion and the rights of homosexuals and transexuals a right to a guaranteed income – rights that only government can provide. The bias it contains in favor of government inaction is responsible for the public’s loss of faith in government.

ED: How did major policy transformations like the New Deal and Great Society feed into anti-constitutionalism? And what is a “stealth government”?

ML/DH: As the ambitions of the federal government have exceeded its ability to deliver concrete results, citizens have learned to hold two contrary thoughts at the same time: the government is responsible for my social and economic well-being and the government is incompetent, unresponsive, and corrupt. As Americans became acclimated to receiving benefits from the federal government— from Social Security to Medicare to discount student loans – the “legitimacy barrier” was broken. It became no longer necessary to ask if a policy was constitutional, only whether it was good. Since the New Deal, the government has attempted ever more ambitious programs of reform, thus increasing the chances to fail. Hence, the growing distrust and disenchantment with government, even as citizens continued to enjoy the fruits of the entitlement state.

Many reforms have been successful, but many have failed because they cut across the constitutional grain.

ML/DH: As in carpentry. Following the grain makes the achievement more stable and durable. Article One provides a good guidepost as to what the government can adequately perform. Hence when the government attempts to micro manage schools, prisons, police forces, bathrooms, and consumer choice, it is cutting across the grain. Much of this excess was spawned during the Great Society as exemplified by the “War on Poverty.” Even though conservative have held the presidency and at least one house of Congress often since 1968 they have not stemmed the tide of constitutional grain cutting. This is mostly due to “stealth government,” which takes advantage of Congress’s paralysis to empower government agencies, in collaboration with the courts and Congress, to move beyond their proper authority to enact sweeping policy changes.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about the American political tradition?

ML/DH: The American political tradition is a mix of liberal, communitarian principles. The Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights proclaim our commitment to liberty.

The Constitution established the liberal principle of government by consent –“We the People”- and provides a framework for enabling an energetic government that is compatible with liberty.

Did you know?

Because we are constituted as a federal republic state, they retain the police power and are therefore charged with providing indispensable supplements to pure liberalism – the preservation of community ties: the cultivation of an active educated citizenry, protection for families, regulation of land use. States delegate much of this power to localities, enabling them to pursue the communitarian principles first enunciated by John Winthrop’s “City on a Hill” Speech.

Most Americans have some understanding of the key constitutional principles of separation of powers and checks and balances. But they do not fully understand the essential contribution of Federalism to preserving and protecting the liberty and stability of the nation. The United States is a country of 333 million people with a very diverse racial, religious ,and ethnic population. It cannot be governed centrally without a heavy dose of authoritarianism. Federalism and the institutions that protect it, such as the Electoral College and the Senate, enable it to enable states to bring size and diversity down to manageable levels.

ED: Which features of modernity worried the founders, and how did their actions assuage their own fears and those of ordinary Americans?

ML/DH: The founders were worried about a number of problems that seemed endemic to modernity. First of all, there was the enormous scale of modern states, and it was clear in the American context that the United States would become even bigger in a relatively short space of time, probably stretching all the way to the Pacific. Second was the commercial and entrepreneurial nature of the American people, which made Americans restless and somewhat insecure (a trait that Tocqueville would note decades later). The current New Hampshire state motto sums it up perfectly: “Live free, or die.” Truculence would seem to be an American trait. Given the unsuccessful tenure of the Articles of Confederation, it was also clear that the country was going to need a real national government, one with the power to coerce the states into obedience if necessary, and to impress the population with the seriousness of federal law.

ED: How would you explain the basic aspects of constitutionalism to non-scholars?

ML/DH: I don’t think that the fundamental aspects of constitutionalism are difficult to explain to non-scholars—our book, certainly, is not written exclusively for a scholarly audience.

What the founders were trying to accomplish can be simply stated. They were trying to create a government that rested on a popular base, and which could be trusted with enough power to actually govern effectively.

ML/DH: The voters chose the Congress; state legislators chose the Senate; and electors chosen by the states chose the President. But the members of Congress had what passed for long terms at the time (4 years), while members of the Senate served even longer (6 years). The President, meanwhile, could in theory be elected to as many terms as he chose to seek. The states would continue to exercise the “police power”—the power to regulate the health, welfare, and morals of the people. This meant schools, public health, infrastructure such as roads and canals: all of the things that shape public and private life in the states and municipalities. This is a complex division of power, always subject to argument, but it makes the United States unique among modern democracies.

ED: You examine several anti-constitutional historical figures while tracing the lineage of anti-constitutionalism in America. Who were some of these figures, and what were some of their arguments?

ML/DH: Of course the first of these figures are those who constituted the “Anti-Federalist” faction during the Constitutional debate, and we discuss their important critiques, some of which led to changes during the Convention debate itself (readers may be surprised at some of these changes).

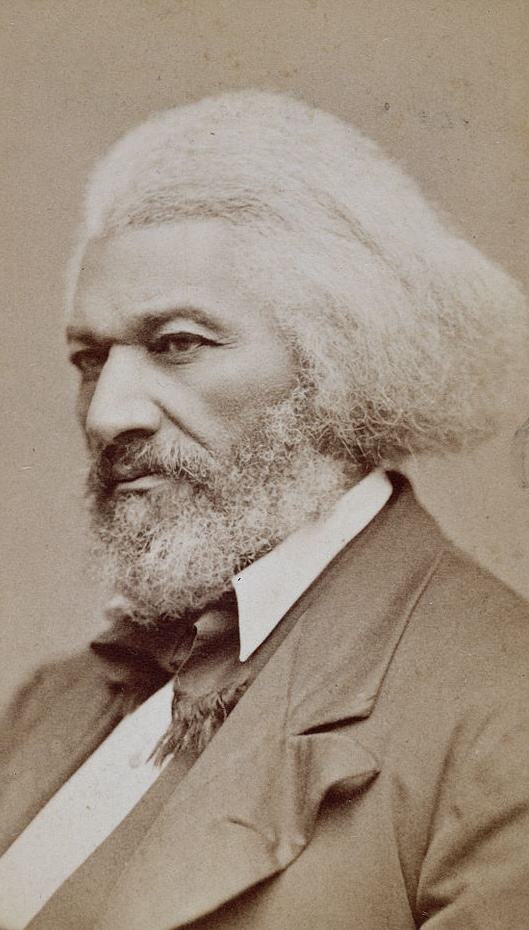

We then look, in turn, at: the anti-slavery critique of the Constitution; Henry David Thoreau; the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who changed his mind about the Constitution, concluding that it did not “authorize” slavery at all; the late 19th-century “utopians” who were concerned most of all with the disruptions caused by industrial capitalism; the original “progressives” (Herbert Croly, Teddy Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and FDR); and the modern progressives, such as the 1960s-era Students for a Democratic Society, along with the highly consequential reform program of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

ML/DH: What I have learned is that the writing of the Constitution was one of the most remarkable events in the history of modern states. The document it produced after a long debate has helped to make America one of the most successful of modern states: stable, prosperous, and consequential. There’s a reason, after all, why so many people want to live here, and it’s not the weather. Furthermore, it was written in such a way that it could accommodate a number of political developments, not all of them predictable: industrialism, global war, even a civil war over the question of slavery. People who are tempted to despair of the country’s future really need to read this book.

ED: Thank you for your time and insights!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).