An interview with Daniel Gullotta

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Daniel Gullotta to discuss his work on Andrew Jackson, and the changing religious landscape of the United States. Dr. Gullotta is a postdoctoral research associate at the Declaration of Independence Center for the Study of American Freedom, based at the University of Mississippi.

America at its core

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

DG: I’d be lying if I said Indiana Jones didn’t have some influence… But in truth, my passion for history comes largely from my father. I have vivid memories of watching historical documentaries with him—he was fascinated by it all, no matter the era or location. Whether it was the Samurai, Ancient Romans, World War II, or Martin Luther, he would be completely captivated and shout, “Dan, you’ve got to see this!” His enthusiasm was contagious, and it’s what first sparked my own love for history.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

DG: I specialize in religious history, specifically American religious history. Like many millennials, I am very much a product of 9/11 and its aftermath. While I don’t recall all the details from that time, one thing that stands out is when I first learned that religion played a significant role in the attacks. This realization opened a can of worms for me, sparking a lifelong fascination with how religious beliefs influence the actions of historical figures.

Religious questions, Jacksonian answers

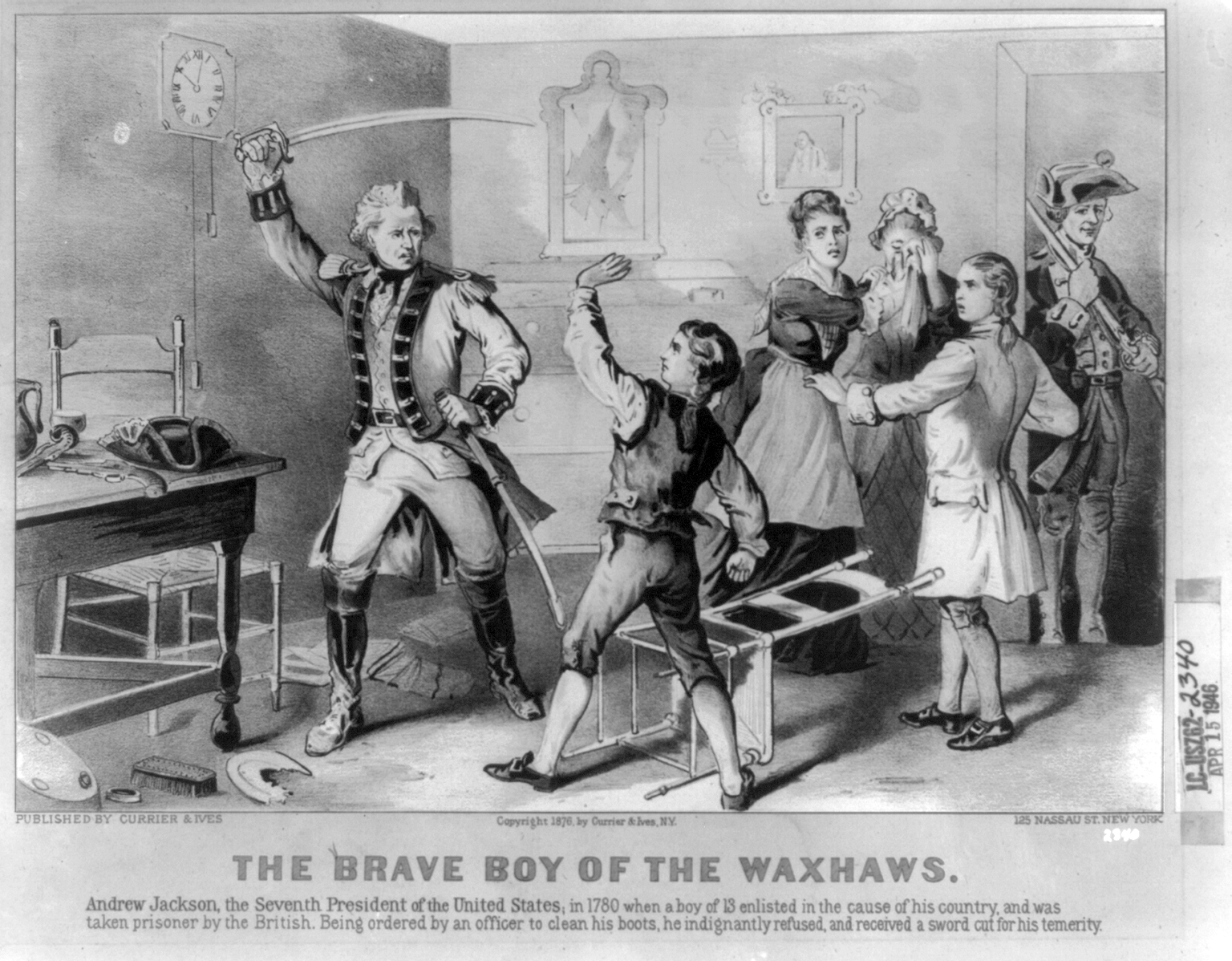

DG: My focus on the early 19th century and the rise of Andrew Jackson was shaped by several factors. One key reason is the noticeable gap in scholarship. While the religious politics of the Whigs have been extensively studied, far less attention has been given to the Democratic Party of that era. This gap inspired me to delve into the religious dimensions of Jacksonian Democrats. Beyond this academic motivation, I also find Andrew Jackson himself incredibly compelling. While waiting for my Green Card, I devoured a number of biographies, and when I came across Jackson, I was struck by how fiercely historians disagreed about him. The debate surrounding his legacy made it impossible not to be drawn in.

ED: Clergy members supporting a dueling slaveholder like Andrew Jackson sounds counterintuitive. Who were some of the religious figures who aided in Jackson’s rise, and what does their support of Jackson tell us about the extent to which religion and politics were intertwined in the 19th century?

DG: That’s a great question, and we can identify some clear patterns among the clergy who supported Jackson. First and foremost were ministers who were personally connected to Jackson or had direct experience with him, such as the chaplains who fought alongside him during the Creek War or his close friend, Ezra Stiles Ely, a Presbyterian minister who corresponded with him regularly. Others were likely motivated by the fact that Jackson was open, though not preachy, about his orthodox Christian faith and regular churchgoing. For many clergy, this openness, coupled with his seemingly miraculous victory at the Battle of New Orleans, was seen as a sign that God was working through Jackson. This led some ministers to make overly optimistic predictions about Jackson’s presidency, including the hope that he would enforce Sabbath observance (something that, of course, never materialized). For many clergy, however, their support boiled down to a deep-seated opposition to John Quincy Adams’ Unitarianism. While they may not have been entirely comfortable with Jackson’s dueling, drinking, slaveholding, and controversial marriage, they saw him as an orthodox Christian, which was preferable to a Unitarian president.

ED: Do you see any parallels between how 19th and 21st-century Americans grapple with the political fracturing of American Christianity?

DG: There are striking similarities in how politically active Christians navigate candidates today and in the past. Just as some now claim Trump is God’s anointed, there was a comparable fervor among those who viewed Jackson as a providential figure. Or how some parts of the media hyped up Hilary Clinton’s Methodism in the same way others hyped up Jackson’s churchgoing. Similarly, many devout Christians today wrestle with supporting candidates like Harris or Trump, struggling to reconcile their political choices with unwavering pro-life convictions—much like 19th-century Christians grappled with their own moral and ethical dilemmas when backing political leaders who were slaveholders. While the specific issues may differ, from slavery to abortion, the broader challenges remain.

Then as now, some Christians struggle to find a candidate who aligns with their godly ideals.

DG: Others are willing to overlook flaws in pursuit of certain policies. Some even attribute near-messianic qualities to their preferred candidate. Meanwhile, there are those who opt out of politics entirely, believing it to be a corrupting force that distracts from higher, spiritual callings. If I have learned anything, it is that the command to “render unto Caesar” becomes much more complicated when you have a say in choosing who Caesar will be.

ED: Describe why American Catholics were attracted to the Democratic Party during the 19th century.

DG: There was no single reason for Catholic support of the Democratic Party, and historians have highlighted several of the most obvious factors. These include the party’s supportive stance toward white immigrants, its advocacy for religious freedom, and its tolerance compared to the more evangelical, nativist flavor that later developed out of the Whig Party. But one aspect less frequently discussed is Jackson’s personal connections to Catholicism. While not Catholic himself, Jackson was of Scots-Irish descent, which led many Irish Catholic immigrants to view him as a kindred spirit, a fellow “son of the smock.” Additionally, Jackson’s defense of New Orleans, a predominantly Catholic city, held significant symbolic value for Catholic Americans. Lastly, Jackson made history by appointing the first Roman Catholic to the Supreme Court: Roger B. Taney.

ED: Tell us about your next project.

DG: My next project explores the colonial period through the lens of magic and witchcraft. While I share the fascination many historians have with the Salem witch trials, I’m equally frustrated by the disproportionate focus they receive—especially when it comes to New England. My goal is to craft a more comprehensive history of witchcraft and magic in the colonies, one that extends far beyond New England and doesn’t conclude with 1692. The real work begins next year during my visiting fellowship at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford University. It feels daunting at times because it is so much bigger than anything I have worked on before, but I am incredibly excited to take it on.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

DG: The debate over whether America is fundamentally a people or an idea has been ongoing for generations.

The more I study the nation’s founding, the more I am convinced that America is, at its core, an idea.

DG: While nations have always been subject to criticism, the critiques of America from outsiders, visitors, as well as its citizens during its early years are striking. They focus intensely on America’s ideals, particularly liberty, and often hold the nation to account for those very principles. There is something hauntingly beautiful about that: a country being challenged by the standards it set for itself. I think that is why pieces of writings like Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and King’s I Have A Dream are so effective. They recall our past as they face their current crisis. Growing up in Australia, we studied Australian history somewhat out of a sense of duty and historical appreciation. But I do not really think it informed our identity all that much. But in the United States, history feels deeply intertwined with our past, present, and future, making the study of it not just an academic exercise, but a part of the nation’s ongoing story. As a historian, it raises the stakes for your historical engagement, but it also humbles you. This is why I love the phrase “the American experiment.” Experiments are messy and rarely go perfectly the first time around. But we keep at it in hope of forming “a more perfect union.”

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

DG: I could give lots of emotional answers, but I am going to just swing for the fences and say I wish more people knew about Martin Van Buren! If you want to understand so much of how our politics became the way they are, for better and for worse, you need to learn about Van Buren.

ED: Thank you for your insights and time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Manager of the History Initiative. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).