An interview with Brianna Frakes

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Brianna Frakes to discuss her early historical inspirations and her work on the Norfolk Race Riot of 1866. Dr. Frakes is a grant writer at American Battlefield Trust, teacher for the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, and Gettysburg College MA Program.

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

BF: I grew up outside of Philadelphia, so visiting historical sites like Valley Forge and Brandywine as a youngster was always fun. My family attended a Civil War reenactment when I was 8 years old, and it really changed my life. I caught the history bug! The ability to engage with reenactors and experience living history left a big impression on me, and I never looked back and was all about pursuing history and historical learning. I was fortunate throughout my middle and high school education to have several influential history teachers who were just great at their jobs. They were so passionate about the field and stoked that interest in me and really encouraged me to learn history. They were, in large part, one of the main reasons I wanted to become a history teacher.

I attended Gettysburg College for my undergraduate studies, and it was the perfect place for someone like me to study history and education. Having the battlefield right there and seeing how my professors used it as an outdoor classroom furthered my desire to become a historian and a teacher. I’m grateful to my family for introducing me to history and to the excellent teachers I’ve had throughout my education who helped me develop that interest into a real passion and career.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

BF: My area of specialty is the Civil War era. Ever since my family trip to a Gettysburg reenactment, I’ve been in love with Civil War history. While we were there, a reenactor pulled me onto his horse and explained the entire reenacting camp to me. I have no memory of what he said, but it ignited a love of history in me and is a feeling I’ve never been able to shake. I study the Civil War era because it is such a rich period in American history that has incredible depth to it and so much intrigue and complexity.

My particular interest is in how Americans came to understand the Civil War and what it meant for them and their lives.

BF: I study this thread primarily through social and military lenses and explore how they overlap with each other and in what ways. I think it is fascinating to recover the stories of people from the past who thought deeply about this great conflict and tried fashioning solutions to the problems that stemmed from it. These people were not famous or in positions of power, but they had opinions and stories that are worthy of telling. I always tell my students that most of us won’t become famous celebrities or presidents, but we still have thoughts and opinions and when we are the people of the past those sentiments deserve to be resurrected so future generations can best understand us and our times.

ED: Tell us a bit more about the Norfolk Race Riot of 1866. Why should every student know about this tragic event?

BF: My dissertation examined the critical port city of Norfolk, Virginia, during the Civil War and early Reconstruction years, and argued that it experienced during wartime many of the issues that would come to plague Reconstruction. It was a fascinating place to study because it was captured by the Union military early in the war (May 1862) and was under occupation until Virginia was admitted back into the Union as a state in 1870. The white civilians in Norfolk were largely pro-Confederate, but there also were white Southern Unionists and a substantial African American population (and a politically active one, too). Add the Union Army to the mix with those three groups and it created a rather tense dynamic. This exploded in a violent episode on April 16, 1866, where African Americans in Norfolk paraded throughout the city in celebration of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

The 1866 Norfolk Race Riot

BF: White civilians objected to this parade and attempted to disrupt it by throwing bricks and bottles at its participants. This quickly escalated as gunfire erupted, dispersing the crowds. Things escalated further as former Confederates then donned their gray uniforms and marched throughout the city in formation, shooting at African Americans and the Union soldiers who attempted to subdue them. Dozens of people were shot and several killed before order was restored. Grant ordered a congressional inquiry into this riot roughly a month later. The testimony offers great insight into the incredibly challenging on-the-ground reality of the immediate post-Civil War years, especially with race relations and military occupation. As an Upper South state, students don’t tend to think of Virginia as a place where race riots occur (compared to the Deep South), but this incident reveals that African Americans and the Union occupying forces were up against considerable forces who were determined to prevent further social and racial changes in their society. (Photo of Norfolk, Virginia, 1864)

ED: Can you share your favorite primary source that you uncovered during your research?

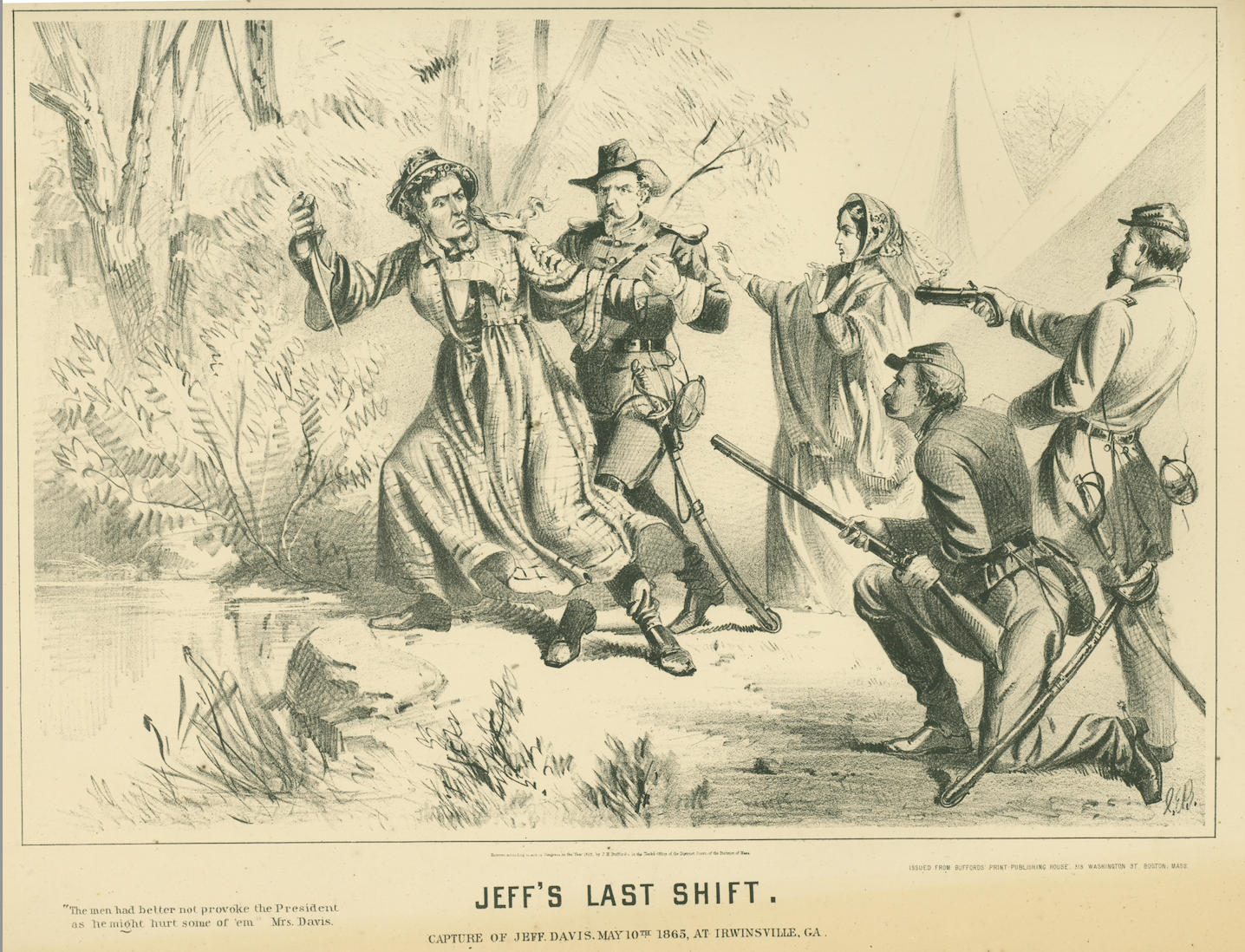

BF: I love primary sources and how they can capture a moment in time. My all-time favorite primary source actually comes from research I did as an undergraduate. My senior thesis examined Northern public opinion of Jefferson Davis in the immediate post-war years and what the Northern populace wanted the government to do with him. Thousands of people wrote to President Andrew Johnson offering their thoughts and suggestions on what the federal government should do, from executing him to pardoning him to putting Davis in a cage, parading him around, and charging people money to see him to help pay down the national debt.

One man from Wisconsin offered to construct the gallows from which to hang Davis and included a sketch with his letter. This man carefully selected the types of wood he wanted to use for each part, writing that each piece represented the great Union men who fought and died in the war. It was a surprising find and intrigued me how this person had thought deeply enough about this to write a letter in painstaking detail and offer his services free of charge if the federal government would execute Davis. The letter was powerful on its own, but combined with the sketch really made an impression. I don’t know what came of the author or if Johnson ever read the letter, but I am glad it’s preserved to offer that snapshot of the real feelings and tensions at the Civil War’s end.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

My research has illuminated how seriously Civil War Americans took the concept of Union and genuinely wanted to preserve the republic.

BF: Of course, the ideas of how exactly to do so existed on a fairly large spectrum and were difficult to reconcile, eventually leading to war itself. My research and the people I’ve studied revealed to me that the founding principles were in many ways integral to the way they viewed their life and their world. What constituted freedom and who could participate in American democracy and to what extent, I found, drove people’s thoughts and actions in small and big ways throughout the Civil War era.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

BF: The amazing thing about the Civil War is that so many people are interested in it for so many different reasons. Unlike other areas of history, the Civil War continues to fascinate people and has incredible relevance to us today as a society. I think the tendency to simplify history and have its complex issues fit into neat boxes is a disservice to students studying all history but especially American history.

For me, one thing I wish every student knew about American history is that, just like them, the people of the past were complex beings and don’t always neatly fit into prescribed categories.

BF: We’re fortunate to have such a wealth of materials from the past and its people and can learn so much from them, sometimes things that people at the time did not even know. I think the Civil War is a great period of history to explore those complexities and the choices people made given their circumstances.

ED: Thanks so much for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).