Slave catchers all!

How the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 helped bring about the Civil War. Adam Gibson stared into the barrel of the slave catcher’s pistol: a free Black man living in 1850s Philadelphia, Gibson was a prime target.

“Forces in operation which must inevitably work”

Adam Gibson stared into the barrel of the slave catcher’s pistol: a free Black man living in 1850s Philadelphia, Gibson was a prime target.

For decades, slave catchers, as well as slaveholders and professional kidnappers had prowled the streets of the city, assaulting Black Americans by any means to enslave them. And while black and white Pennsylvania abolitionists, especially those living in Philadelphia, fought tooth and nail to protect the Black community, even persuading state officials to pass “liberty laws,” that placed hefty fines on kidnappers, slave catchers, and even slaveholders, the recent passage of the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 rendered all their efforts obsolete.

Thus, Gibson may not have been the slightest surprised when the notorious slave catcher George Alberti, Jr. and his minions arrested him and dragged him to the Old Statehouse. Alberti suspected that Gibson was a fugitive from slavery named Emery Rice. Now with the power of the federal government behind him, the slave catcher had no qualms bringing Gibson before a federal judge and “returning” him to slavery. But how did the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act come about?

Everyone knows how freedom and slavery jostled for position during the founding of the United States. Several founders own enslaved people while affixing their names to a Declaration of Independence that pronounced “all men are created equal.” Debates over enslavement rocked the Constitutional Convention. The infamous Three-Fifths Compromise between the slaveholding states and the states that abolished slavery or passed gradual abolition laws apportioned extra representatives to the slaveholding states by counting three-fifths of the enslaved population and ushered in decades of southern dominance in Congress. Furthermore, slaveholders and their northern allies came to dominate the presidency: John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln represented the only non-slaveholding, non- “Doughface” (i.e., northerners with southern sympathies) presidents prior to the Civil War.

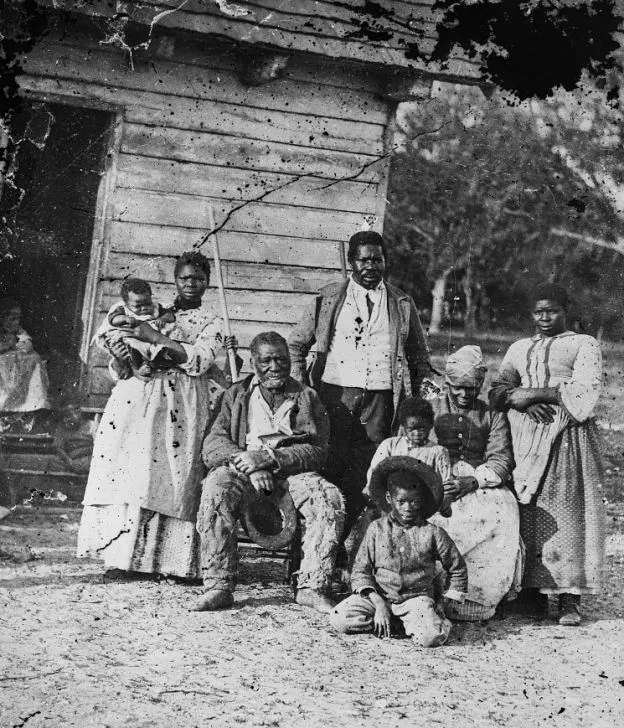

Black Americans living under slavery, especially those in Virginia and Maryland, took to heart the promises of the Declaration of Independence, which reflected their own inherent drive for freedom. Incidents of fugitives from slavery fleeing the south into states like Pennsylvania helped crystallize slaveholders’ resolve to protect and retrieve their so-called property.

The 1791 case of John Davis, a Black American kidnapped by three Virginians, further pressured the federal government to intervene in how best to handle the kidnappings of free Blacks as well as the “legal” retrieval of fugitives from justice. Davis’ kidnapping prompted Pennsylvania Governor Thomas Mifflin to request the extradition of Davis’ kidnappers from Virginia. However, Virginia Governor Beverly Randolph claimed that Davis was a runaway, and thus, refused to extradite the men. Mifflin asked President George Washington to resolve the matter.

Washington soon encouraged Congress to pass a law regarding extraditing kidnappers and retrieving fugitives from slavery.

Despite a constitutional clause stipulating that escaped persons “held to service of labor,” (i.e., criminals, indentured servants, and most importantly, fugitives from slavery) be “delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labor may be due,” Congress passed the first Fugitive Slave Act in 1793. This law stated that state and local governments must assist slaveholders in retrieving fugitives from slavery and more importantly, gave slaveholders and their “agents” (i.e., slave catchers) permission to search for and arrest Black Americans in the free states.

Further complicating matters, states like Pennsylvania had already passed gradual emancipation acts, as well as anti-kidnapping laws, to protect free Blacks living in their states. Black and white abolitionists in Pennsylvania immensely influenced the creation of what became known as “liberty laws.” In short, these state laws sought to prevent kidnappers, slaveholders, or slave catchers from kidnapping free Black Pennsylvanians and punished kidnappers with steep fines and jail time. Not only did these laws reflect the intertwined realities of Blacks fleeing southern slavery and the kidnapping of free Blacks throughout the North, but these laws also revealed how some Americans, namely Black and white abolitionists, strived to live up to the promises enshrined in the Declaration of Independence.

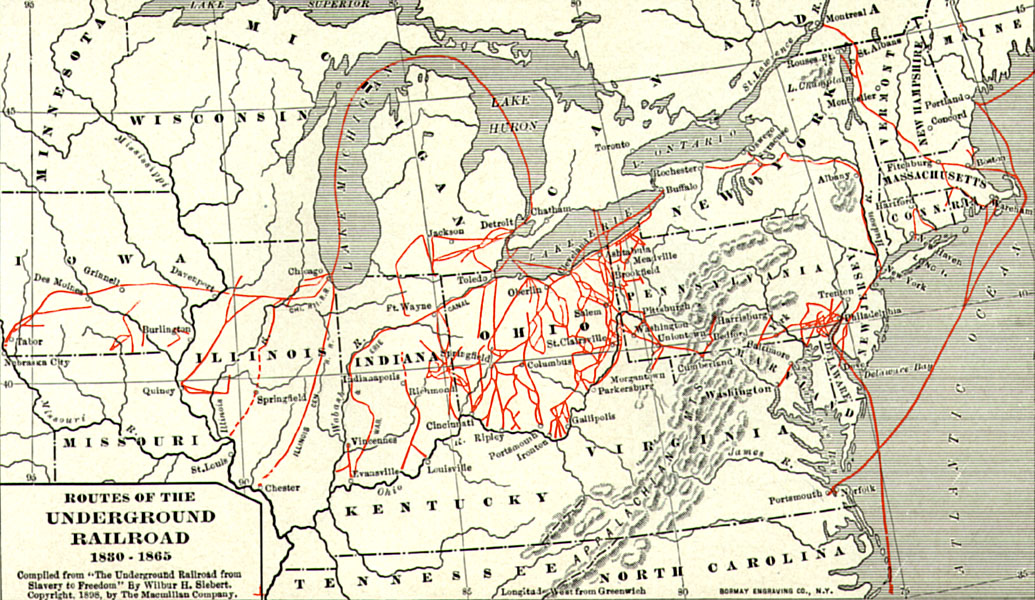

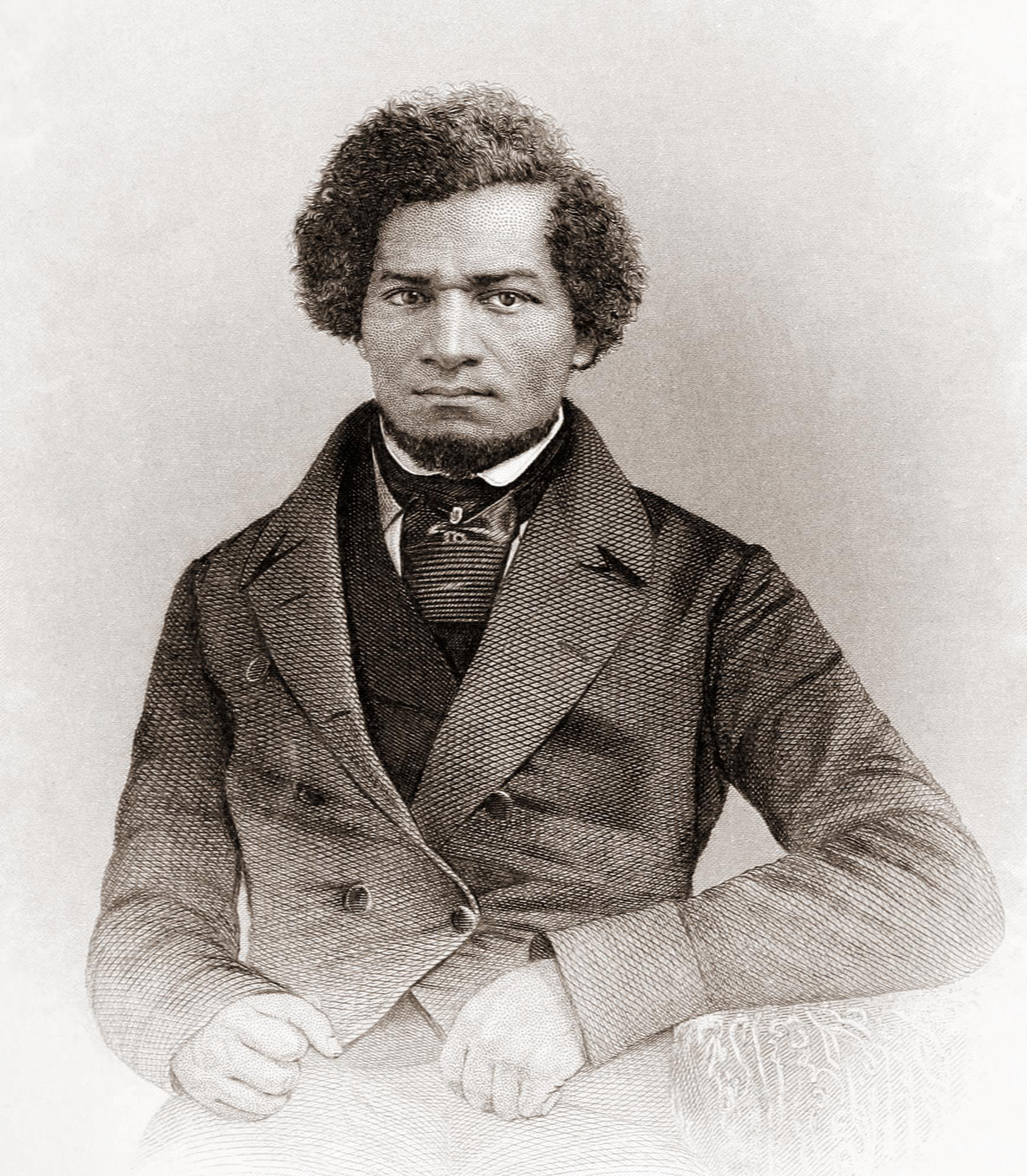

By 1850, a slew of northern states followed Pennsylvania’s lead and enacted their own liberty laws to the chagrin of slaveholders. Southerners believed they possessed the right to track and capture Black Americans throughout the Union and viewed northern state’s liberty laws as a threat to maintaining peaceful relationships within the Union. The rise of aggressive abolitionism and the national celebrity of Black Americans like Frederick Douglass as well as the ongoing public successes of the Underground Railroad further exacerbated slaveholders’ patience. Southern slaveholders (and some of their northern colleagues) believed that only federal legislation could solve the fugitive slave crisis, protect slave state interests, and save the Union.

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act fully immersed the federal government in the process of retrieving fugitives from slavery. Slaveholders and slavecatchers could now enlist the help of U.S. Marshals to retrieve fugitives from slavery anywhere in the Union. Federal commissioners and judges now possessed the authority to issue warrants to slaveholders and slave catchers, overriding state officials who might refuse to become involved in fugitive slave cases. Furthermore, slaveholders’ testimonies would be valid while the accused could not testify at all. If the court ruled in the favor the slaveholder, they then had the power to request that U.S. Marshals hire as many people as necessary to bring the enslaved back South.

Most importantly, anyone who interfered with the arrest of an accused fugitive faced a fine of $1,000 and up to six months in jail. In short, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act made all Americans, whether northern, southern, white, Black, male, or female, responsible for assisting slaveholders in their pursuit of fugitives from slavery.

Returning to the Gibson case, the presiding Federal Commissioner was Edward Ingraham, who for years represented slaveholders who came to Philadelphia in search of runaways. Since Gibson lacked the ability to defend himself in court, Ingraham sided with the slave catchers and ruled that he was in fact a runaway. The slave catchers hustled Gibson out of court and transported him to Maryland. There Gibson’s supposed owner told the slave catchers that while he recognized Gibson and did not how Gibson ended up in Philadelphia, “he was not his slave.” Gibson returned to Philadelphia triumphant, but no doubt shaken by the experience.

Gibson and other Black Americans faced the wrath of the Fugitive Slave Act throughout the 1850s. Black Americans and their white allies took increasingly desperate measures to protect themselves by planning and executing daring rescues, secreting runaways through the network of Underground Railroad stations, and even killing would-be slave catchers and slaveholders. The catastrophic consequences of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act exposed the inherent danger to all Americans who lived under the rule of law: Black Americans could be arrested and assaulted at will under the auspices of the federal government, and white Americans who sought to protect them faced the reality of fines and jail time. And while the number of abolitionists remained small throughout the decade, the fundamental inability of slaveholders and slave catchers to differentiate between free and runaway epitomized the paradox of freedom and slavery in the United States.

A catastrophic series of events throughout the 1850s further exposed the consequences of American slavery and freedom. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, Bleeding Kansas, the Dred Scott Decision, and the collapse of the Second Party System weakened the bonds of Union even further. The Republican Party soon emerged as a viable political party with a platform proclaiming the non-extension of slavery.

Fittingly, Republican Abraham Lincoln noted in his 1858 House Divided speech that the United States could no longer “endure, permanently half slave and half free.” Two years later the slave states would secede to protect the enslaved half of the nation.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 helped bring about the Civil War due largely to the actions of fugitive slaves and the response of northerners forced to be complicit in a system they despised. Instead of treating slavery as an abstract system confined to the southern states, the act gradually revealed to northerners how slaveholders would stop at nothing to retrieve their so-called property, northern liberty laws and “all men created equal” be damned. And while many northerners would stop short of considering themselves abolitionists, the rise of the Republican Party and its antislavery extension underpinnings spoke to northerner’s desire to dash the hopes of territorial aggrandizement concocted by slaveholders.

During the dark rumblings of the early 1850s, the most famous fugitive from slavery, Frederick Douglass, stated how even he “did not despair” of his country. Instead, he knew that forming a “more perfect Union” required “forces in operation which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery.” In a way, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 represented the beginning of the end for American slavery, as the actions and inspiration of those who fought against enslavement would prove decisive in reshaping and helping realize American freedom.

This post was also featured on RealClear History.

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).