Remembering the courage of an American pioneer

Amelia Earhart pilot gazes up at the sky, wincing in anticipation. Remembering the indomitable courage of an American pioneer.

Because I want to.

Her eyes scan the majestic, cloud-covered horizon as a dozen or so residents of Lae, Papua New Guinea, assemble in front of her aircraft to see her off. Soon thereafter the navigator lends the pilot a hand, and with a quick tug, lifts her onto the wing. Gingerly, she trots up the slope of the wing, throwing one leg over the hatch, and descends into the cockpit. Within minutes, the plane takes off down the runaway.

Those were the final moments of Amelia Earhart captured on film.

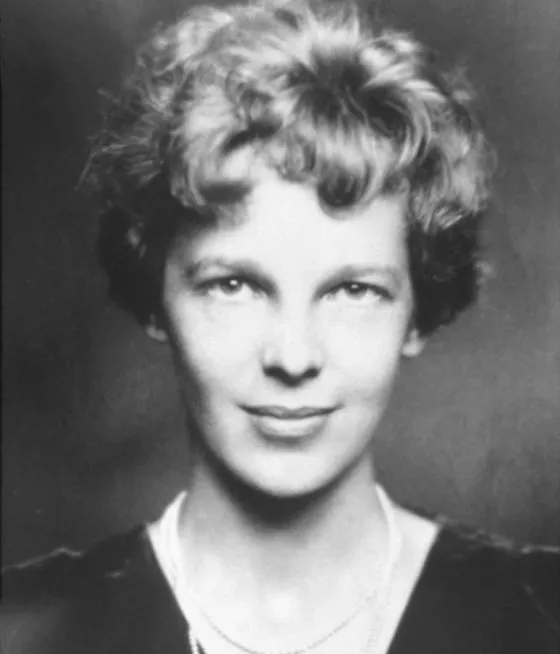

Amelia Earhart was born on July 24th, 1897, in Atchison, Kansas. A rambunctious child, she flouted social conventions from a young age, playing basketball, roughhousing, exploring the woods by her home, climbing trees, and hunting. The little girl with auburn hair never failed to stand out as an ambitious, sometimes impatient, individual.

At age seven Earhart saw a rollercoaster at the World’s Fair in Saint Louis, Missouri, which Inspired her to create one of her own in her backyard. The feeling she felt speeding down the makeshift greased-up track, soaring into the open air, and completing her first flight with a rough, improvised landing, became the metaphorical pebble one tosses into a pond, generating bigger and bigger waves that augured her eventual love and life of flight.

At age 10 she saw an airplane for the first time at the Iowa State Fair. Later, she said of the experience that the airplane was “a thing of rusty wire and wood and looked not at all interesting.” This memory stuck with her as she longed for an escape that her tempestuous home life failed to offer her. Earhart’s father, Samuel, held a job as a legal representative for various railroads, and the Earhart family moved often, from Kansas to Iowa to Minnesota. Her mother, Amy, tired with her husband’s drinking and income insecurity, left him and took their daughters to Chicago, where Amelia attended six different schools in four years.

Did you know?

After graduating high school, Amelia enrolled in auto repair courses and briefly attended Columbia University. With the outbreak of the Great War, she served as a Red Cross nurse’s aide at a Canadian military hospital in Toronto. In 1918 she attended her first flying exhibition, later recalling how one stunt pilot dove toward Amelia, thinking she would “scramble.” Earhart held her ground as the plane roared by her and thus began her lifelong love affair with aviation.

When the war ended, Earhart moved to California to live with her parents, who had by this time reunited. In 1920, she took her first plane ride. This became another revelatory moment in her life, as she said later that she knew that she“had to fly” – in other words, she must learn to fly as a pilot herself. She began flying lessons with the noted aviator Anita “Neta” Snook, and over the course of six months worked a variety of jobs in order to purchase her first airplane at age twenty-five, a yellow Kinner Airster Biplane she nicknamed “The Canary.”

The remaining decade and a half of Earhart’s life was a whirlwind of achievements, each headier than the last: between 1922 and 1937, she set seven women’s speed and distance records, and became the first woman to fly an autogiro (a hybrid of a helicopter and propellor plane), the first woman to fly solo and nonstop across the United States (1931), and the first person to fly solo from Honolulu, Hawaii to the mainland United States (1935).

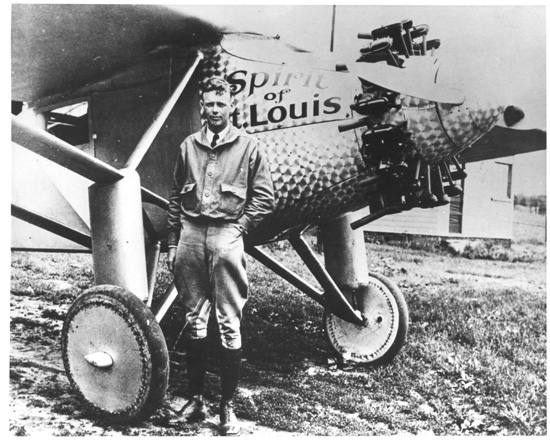

Despite these accomplishments, Earhart’s most famous flights occurred in 1928 and 1932. Charles Lindbergh’s iconic first-ever transatlantic flight in 1927 put Earhart in the spotlight, owing both to her rising fame as an aviator as well as the support she received from her publicist and soon-to-be husband, George Putnam.

However, rather than pilot the plane herself, Earhart was a passenger – in her words, “I was just baggage, like a sack of potatoes” – while two men, Wilmer Stultz and Louis Gordon, flew the plane. The plane left Newfoundland on June 17th, 1928, and though hampered by poor visibility and icy conditions, landed safely in Wales to a cheering crowd. Railey was one of the first to congratulate Earhart, who smiled and told him, “maybe someday I’ll try it alone.”

By this point, Earhart had become an international celebrity whose ambition knew no bounds. With her husband’s publishing company and public relations finesse, she wrote a bestselling account of the 1928 flight titled 20 Hrs., 40 Min. She also embarked on a two-year lecture tour, often speaking in multiple cities in a single day, all the while urging Americans to reckon with assertive, intelligent women such as herself:

Twenty years ago the idea that woman could learn to drive automobiles was considered preposterous. The eternal bogies, feminine nerves and physical weakness, were advanced as final and conclusive arguments when all others failed…if anything, virtually all of woman’s experience and training has been of the sort to give her nerves of iron. No man could endure for a half hour what is just part of a day’s work to a woman…

She became the Aviation Editor of Cosmopolitan, launched a short-lived fashion house in Macy’s with clothes that she designed, served as the first female vice president of the Boston chapter of the National Aeronautic Association, and helped found the Ninety-Nines, the first organization for women aviators.

By 1932 she made good on her words to Railey and became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic. Yet this flight was not without its hurdles: as in 1928, she flew through cloudy and icy conditions, but this time, the plane also developed a fuel leak during the trip and her altimeter failed. In danger of crashing, she landed on the first piece of land in sight, which was a small pasture in Northern Ireland. This endeavor earned her the Distinguished Flying Cross from Congress for “heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in an aerial flight.” In 1933, she visited the White House, where she met President Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the latter of whom became one of Earhart’s biggest supporters.

During this time, she continued lecturing both in-person and over the radio to promote her book and act as a spokesperson for women’s equality. Her most famous speech, “A Woman’s Place in Science,” (1935), linked technological and scientific processes to liberation for American women.

Earhart used her platform as a role model and public figure to meet and encourage women. Aviation, writing, and public speaking, she explained, gave her the “opportunity to know women everywhere who share my conviction there is so much women can do in the modern world and should be permitted to do irrespective of their sex.”

In 1935, Earhart set her sights on her most ambitious project yet: “a circumnavigation of the globe as near its waistline as could be.” When asked by reporters and fans why she wanted to become the first woman to travel fly around the world, she always replied, “Because I want to.” A woman who led by example, she found great satisfaction showing that women could “do things by themselves if given the chance.”

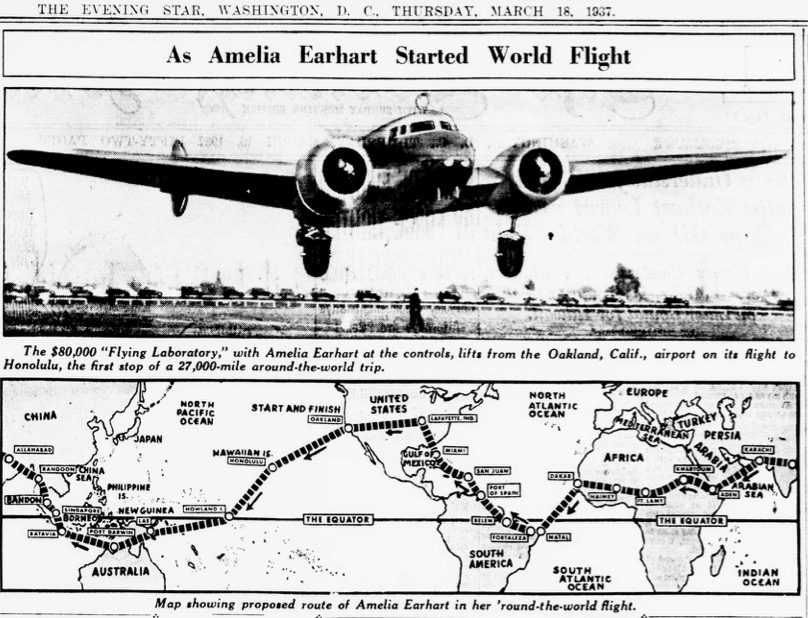

Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, went to work preparing for their world trip. Flying a sleek silver Lockheed Electra, the pair would travel east to west, from Oakland, California to Honolulu before crossing the rest of the Pacific Ocean and landing on Howland Island, a small atoll halfway between Hawaii and Australia. The first leg of the journey hit a snag: in Honolulu, they suffered what aviators call a “ground-loop” (i.e., the uncontrolled rotating of the aircraft while still on the ground) while taking off, which resulted not only in damage to the plane’s underbelly but also led to a complete overhaul of the world trip.

The second attempt began on June 1st, 1937, when Earhart and Noonan decided to fly west to east. Perhaps to save time and conserve fuel, Earhart ditched the stronger radio antenna recommended by Lockheed in favor of a lighter, though weaker, antenna that had trouble sending or receiving messages in inclement weather. She also removed all nonessential items, including the parachutes.

In hindsight, these neglectful actions may have resulted in a successful circumnavigation. However, as biographer her Doris L. Richargued, such neglect by Earhart reflected a character flaw that plagued her throughout her life: impatience. Even more foreboding, Amelia told a friend before takeoff, “I have a feeling that there is just one more flight in my system.”

Over the course of the next month, the pair flew from Miami, Florida, down through South America, crossed the Atlantic to Africa, and then toward India and Southeast Asia. The trip sounds nothing short of superhuman, especially given the technology of the day: on average they flew seven hours per day (and three days flew more than 13 hours) and logged over 180 hours in-air by the time they touched down on Lae airstrip in Papua New Guinea. By that time the pair suffered from “extreme pilot fatigue,” and Earhart appeared gaunt in the last photos taken of her.

The 1,000-foot unpaved runway at Lae served as the final departure point for Earhart. On July 2nd, 1937, Earhart and Noonan prepared for the most difficult (and longest) leg of the trip, 2,500-miles with a minimum flight time of 17 hours to Howland Island. Making matters worse, the weather forecast consisted of overcast conditions, formidable headwinds, and sporadic squalls. After posing for pictures with locals and being filmed for publicity (and posterity), the pair boarded their Electra and took off. Ten hours later, Earhart and Noonan lost radio contact with the United States Coast Guard cutter stationed at Howland Island. Their bodies and plane were never recovered.

What happened on Earhart’s fateful last flight? Some experts posit that the underbelly of the Electra scraped the gravel runway on takeoff, ripping off invaluable radio antennae. Once in the air, radio communication became fragmented, which led to confusion between the plane and the Coast Guard. Factoring in extreme plot fatigue, unforgiving weather, and barely enough fuel to reach Howland Island in the first place, many believe that Earhart and Noonan crashed into the Pacific near their destination. After numerous searches across the decades, we still do not know what happened in those final, fateful minutes.

There’s still so much to learn and appreciate about the life of Amelia Earhart. Her tragic disappearance aside, the virtues of her character shine through more than any of her achievements. Earhart’s fundamental virtue rested in her courage, which as Aristotle reminds us, lies between cowardice and foolhardiness. While her impatience may have doomed the trip, this impatience paid off in other moments of her life and thus need not overshadow the prudential courage she displayed promoting women’s equality and dazzling the world as an aviation pioneer. She lived her life on her own terms through an inexhaustible self-confidence that ought to give all of us the courage to soar above our circumstances.

In her own words, “Courage is the price that life exacts for granting peace, the soul that knows it not, knows no release from little things.”

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Editorial Officer. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).