An interview with Professor Nora Slonimsky

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Scholar Nora Slonimsky to discuss her work and new book, The Engine of Free Expression: Copyrighting the State in Early America. Dr. Slonimsky is Gardiner Associate Professor of History at Iona University and the Director of the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies.

Recently, Dr. Slonimsky was awarded an honorable mention for the Anne Fleming Prize. The prize is awarded every other year to the author or authors of the best article (see below) published in the previous two years in either Law and History Review or Enterprise and Society on the relation of law and business/economy in any region or historical period.

ED: What inspired you to become an American historian?

NS: The very short answer is historical fiction! I’ve shared a bit about this experience before, but essentially, I was inspired to become a historian by A Proud Taste for Scarlet and Miniver by the inimitable E.L. Konigsberg. I spent a lot of time as a child at the Met Cloisters in northern Manhattan, and so picked up a copy at an elementary school scholastic book fair because the cover reminded me of the unicorn tapestries.

That book fair kicked off several years of reading (or more accurately, inhaling) as much historical fiction as I could: Ellis Peters, Steven Saylor, and Sharon Kay Penman were my absolute favorites. Within a few years I wanted more details, more context (although I doubt I knew that word yet!) and to read the character’s ‘real words,’ whether they were Cicero’s speeches or Catullus’s poems or the frustrating lack (for both my 12-year-old and 37-year-old selves) of Eleanor of Aquitaine’s own words. I began to realize that I loved reading fiction and primary sources together and that a job existed where I could do both.

While this addresses the historian part of the question, I haven’t yet mentioned the ‘American’ part. The idea of becoming a professional historian came to me when I was an undergraduate at Binghamton University, first in a class where I first read Elizabeth Eisenstein’s The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe and then in “Oral Histories of the Black Experience” with Professor Anne Bailey.

While I’ve been so fortunate to have tremendous teachers throughout my education, it was those two experiences that, while each quite unique from the other, made me realize that I was fundamentally interested in histories of how people communicate, of how they express themselves.

It wasn’t, however, until I was in a master’s program in American studies at the CUNY Graduate Center –at the time I was still unsure if I was better suited to pursue a PhD in history or literature— that I figured out the questions I was most interested in around book history and intellectual and creative labor were most directly suited for study in North America and the Atlantic world. I have a lot of friends and colleagues who had experiences in which their regional or geographic interest drove their specialization, but for me, it was my thematic interest that led to my geographic/regional focus.

ED: Your new book, The Engine of Free Expression: Copyrighting the State in Early America, tackles the issue of intellectual property in early America. What led you to write this book, and what is your central thesis?

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor on the framers

NS: As a first-year graduate student broadly interested in copyright, I read an article that referenced the case of Harper and Row v. The Nation, where the Court deliberated whether or not The Nation, the long-standing magazine, was allowed to print an excerpt of former president Gerald Ford’s memoir. In A Time To Heal, Ford shared for the first time his logic for pardoning Richard Nixon a decade earlier. The Nation argued that it was essential information for the American public whereas Ford’s publisher, Harper and Row, held that it was protected, personal expression. Siding with Harper and Row in her majority opinion, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor argued that the excerpt went beyond fair use, stating that the “framers intended copyright itself to be the engine of free expression.” But did they?

NS: Unaware that the framers had thought much about copyright at all, that question set me on the path for what became Copyrighting the State. Over the course of my research, I became more broadly interested in how people understood copyright, well before there were legal structures, enforceable or not, and how their understanding related to other circumstances in early America.

The central thesis of Copyrighting the State is that over the course of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, copyright was both a tool and product of state formation. Beginning in the colonial period, developing at the state level, and then expanding under federalism, I argue that there was a process of “copyrighting the state,” during which writers and others involved in the making of textual property pushed for institutional recognition of their labor. That push, in turn, legitimized those in positions of authority, strengthening the claims of the writer and the government simultaneously.

ED: Describe your favorite primary source that you encountered while writing your book.

NS: Oh, that is a tough question! Every artifact I draw upon in Copyrighting the State is included because I think it is an integral piece of evidence to understanding the relationship between government and copyright.

Put another way, each source is a piece of the puzzle. When you put all of these seemingly separate issues and circumstances together, a picture emerges showing how copyright, for better and for worse, became a part of our national political economy.

NS: With that in mind, rather than mentioning my favorite source per se, I’d rather focus on the one I found most illustrative of that process.

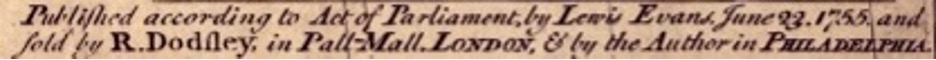

Because Copyrighting the State spans more than a hundred years, each chapter has a source that speaks to a unique moment in the process. But, going all the way back to my initial dissertation research, there is a source that stands out as a eureka moment! Lewis Evans’s A General Map of the Middle British Colonies, In North America, first printed in 1755 in Philadelphia and then a year later in London, is one of the more studied images of the eighteenth century, and was quite a hit when published.

For my purposes, though, I was struck by an easy-to-miss statement in the bottom right-hand corner of the map, a publication line that effectively served as one of the earliest copyright notices in North America, centuries before the now-ubiquitous c-in-circle symbol was introduced. What makes this copyright notice so cool (and if you’re interested, I published an article on it last year in the Law and History Review), is that it illustrates that well before formal legislation emerged, writers and artists and scientists had complex and contradictory emerging ideas about textual property and the place of their work in broader questions about empire, sovereignty, rights, and knowledge.

ED: Reflecting on our current moment, how do you see the rise of AI changing how we conceive of intellectual property?

NS: The relationship between AI and IP is a fascinating one. Two important caveats: first, I think the impact of AI on intellectual property depends on the type of AI and the type of IP. For example, patents and trademarks and their relevance to AI in medicine and public health, might function very differently than copyright and communication.

Second, I think it’s important to note that the relationship between AI and copyright is an evolving one, and things might look different in six months, a year, and so on. With that said, at this current moment, I don’t think AI will have a fundamental impact on how we understand copyright as a form of intellectual property. Rather than seeing change, I’ve been quite struck at how enduring the issues around AI and IP are.

A few weeks ago, I was catching up with a friend and colleague, Zvi Rosen, who is a copyright attorney and professor at Southern Illinois University, and we were having this very conversation. Zvi raised the excellent point that, for those involved in copyright practices, for example Barbara Ringer, the first woman-register of copyrights, AI is neither a new issue nor a surprising one.

Going back to the 1960s, the US copyright office, for example, was focused on computer, or what we can broadly describe as machine learning, creatorship. They drew a distinction between expressions created by a human being, with assistance from technology, and expressions originating from that technology itself. In many of the current circumstances, the Author’s Guild letter, for example, or The New York Times lawsuit against Open AI and Microsoft, it seems fairly evident that the resulting expressions rely on the works of others rather than creating a new expression.

This harkens back to a much earlier historical context, centuries before US copyright law. With the advent of the printing press, another machine with monumental impact, there was also a tension between the origin of the expression (the writer) and those that reproduced it (the printer and the press). As formal copyright laws emerged, another, albeit blurry, metric for what could be copyrighted was whether a text contained statements, ideas, or facts, which are not protected, as opposed to the interpretation or expression of an idea or a fact. In our moment, the question remains whether AI is creating a new, unique expression, or compiling the words of others, and while I can’t predict how courts will decide, there is a fair amount of precedent.

ED: Explain how the growth of digital humanities has influenced how you conduct research and “do” history.

NS: The influence of digital humanities on how I “do” history is two-fold, and foundational to how I approach the different threads of being a historian. Both by preference and by subject matter (early American copyright is a topic often more studied by legal, literary, and bibliographic scholars than historians) all my history work, from scholarship and teaching to administration and public engagement, is interdisciplinary.

Digital humanities are inherently inter- and multi-disciplinary, modeling how such a wide range of expertise, methodologies, and questions can be studied and applied collaboratively. It is the collaborative nature of digital humanities, built upon its interdisciplinarity, that has also greatly influenced how I approach not only my research but each aspect of my job. It is such a privilege to conduct research, whether that is in archives or laboratories, and generate knowledge that in turn can be shared with as broad a public as possible! It can, at times though, be a bit isolating: you’re on your own quite a lot.

In today’s environment, where academia and the humanities specifically are facing so many material challenges, I feel very fortunate to be able to do this work, and as a result, community is that much more important. Not only do I incorporate digital humanities methods, like data visualization or GIS mapping, into my research, I also rely heavily on this dual ethos of interdisciplinarity and collaboration in my classes and in my other work as director of the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies.

For example, last year, we launched a minor program in Digital Humanities and Public History, and it’s been tremendous to see the ways in which students benefit, not only through specific methodological training, but greater media and information literacy, civic engagement, and experiential learning by interning with community partners at historic sites, museums, and digital collections.

Another example is an edited collection organized by the ITPS, American Revolutions in the Digital Age, which seeks to put digital humanities and history of the late eighteenth-century founding era directly in conversation with each other. Edited by Mark Boonshoft, Ben Wright, and myself, it’s coming out in August of 2024 with Cornell University Press, and will be available via open-access, so you can download it for free!

ED: How have your experiences teaching undergraduates inspired your research?

NS: My research and teaching are so entirely intertwined that I would find it difficult to disentangle them! Undergraduate scholars are the best possible audience for test driving your work: if a part of your project stands out to them as exciting or compelling, then you know you have something, and if there are other parts that are confusing, unclear, or don’t make sense, then you need to improve it.

Since I started at Iona, there are two classes specifically that have also generated new research in and of itself. While the themes of each course came out of my broad scholarly interests, copyright and the age of revolutions, respectively, “From Hamilton to Mickey Mouse: Intellectual Property and the Politics of Innovation in American History” and “The Age of Revolutions and Historical Memory,” have given me countless opportunities to both broaden my knowledge of the relevant subjects and hone my specific scholarly and pedagogical interpretations.

For example, because each class intentionally spans a broad chronology, considering changes in intellectual property practices and in how we remember the American, French, and Haitian revolutions up until the present day, I am especially fortunate to learn from my students and how they view these themes in their own day to day lives.

NS: As a result, we are all collaborating and learning from each other. I’ve always been inclined to time-jump, if you will, and see connections across pretty vast chronological gaps (if the answers to the other questions weren’t a giveaway), and I’ve found greater confidence in making those links more explicitly in my published work thanks to my students. My students’ willingness to think creatively and expansively has also inspired a totally new aspect of my research in history, pedagogy, and scholarship of teaching and learning. In each of these courses, I implemented an “un-essay” final assignments, which encouraged students to apply their historical knowledge to contemporary media and formats.

I was then able to publish about our practices with the unessay in Teaching History: A Journal of Methods. In this case, my undergraduate students were directly responsible for a new aspect of my research!

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

The early history of the United States is a rich and complex period for studying copyright, and I’ve found that it often intersects, at times quite deliberately, with several founding-era concerns about freedom of speech and of the press, economic regulation, political and proprietary rights, and the Enlightenment emphasis on education, learning, and civic duty. Put another way, copyright is deeply intertwined with those principles, it’s not a neutral institution or practice, and so experiences similar successes when the principles are realized and failures, particularly involving equality and equitable treatment for all, when those principles fall short.

NS: If I had to pick one singular example of what copyright has illustrated for me about those founding principles and history, I would say it is the critical importance of accurate, authentic expression based on legitimate evidence. There was a deep concern in that critical period about mis- and disinformation, and what that lack of truth or accountability could mean for democracy. Many of the writers I study frequently viewed reprinting, piracy, or unauthorized publication of their work as a form of misinformation.

Part of this was certainly commercial – like any other form of labor, writers need to be paid for their work – but it was also linked to this fear that a reprinted issue could misrepresent or get wrong what the writer intended, and thus create or contribute to confusion or misinform the reader. As media landscapes rapidly change and how we absorb expression changes all the time, this seems like an enduring and important concern.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

NS: It’s complicated! The history of the United States is a balance between unique and meaningful achievements and immense challenges. You have these extraordinary principles, going all the way back to independence, that emphasize values like individual and collective rights, autonomy, equality, education, learning, respect, and so many others, that have ensured tremendous contributions, from peaceful elections to public libraries to national parks, and so many other aspects of our civic society.

And there are several examples where those principles have invoked tremendous good. Yet to study those histories without recognizing the ways in which the United States government and society has fallen short of the founding-era principles, excluding and harming many communities, individuals, and the environment along the way, from slavery to segregation, the denial of Indigenous sovereignty, barriers to suffrage, safety, and gender-equity, is not only dishonest, but also undermines those very principles.

Ultimately, one thing I wish every student knew about American history is its capacity for change. There are hard historical realities that impact our present-day in a myriad of ways. But much like interdisciplinary and collaborative historical work, from my perspective, one of the most significant through-lines across different historical moments is the ability, as cliché as it might sound, to work collectively to build upon and realize those powerful principles for all.

ED: Thank you for your time and insights!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).