An interview with Professor Peter Porsche

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Miller Fellow Peter Porsche to discuss abolitionism, engaged citizenship, and the inspiration he draws from the American past. Dr. Porsche is a lecturer at Baylor University.

History is a vital resource

ED: Why did you become an American historian?

PP: Growing up in southeastern Pennsylvania, my parents took our family to the Valley Forge, Harpers Ferry, and Gettysburg National Parks on an almost yearly basis. These annual explorations of key locations, associated with the American Revolution and Civil War respectively, sparked my interest in American history and my desire to understand more about the significance of the events which took place at these sites. Ultimately, that interest led me to become a historian.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

PP: My research interests lie in the intersection of American Race and Religion with special attention to how these factors shaped debates about and access to US citizenship and its attendant privileges and immunities during the nineteenth century.

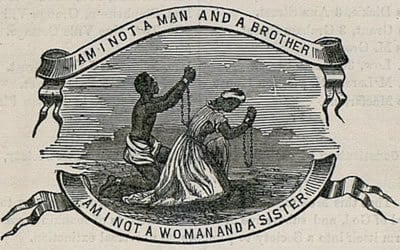

As a person of faith, who believes the Bible teaches the equality of humanity based on all individuals being created in the image of God, my interest in this topic goes back to my youth when I sought to better understand or unravel the inconsistency of a nation shaped by the Bible and egalitarian principles yet deeply committed to the dehumanizing institution of chattel slavery.

Later, as a graduate student, I became fascinated with exploring the individuals involved in the political wing of the nineteenth-century abolitionist movement and the tactics they employed to create a more egalitarian society.

ED: What has your research taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

In brief, it has taught me that these principles, including representative government and individual equality, are contagious and worth fighting to preserve.

ED: Describe your favorite research “rabbit hole,” and the results of that quest.

PP: I am especially interested in the effects of agitation for equal citizenship made by black and white activists during the nineteenth century and how a small biracial group of political and evangelical pre-Civil War abolitionists turned postwar civil rights advocates pushed for equality and colorblind citizenship.

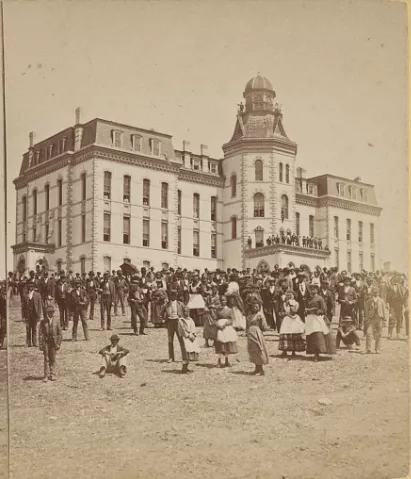

This interest has led me to spend countless hours with documents from the American Missionary Association (AMA) Archives at Tulane University. The AMA was one of the most radical and racially progressive groups of the nineteenth century. It was primarily led by Congregationalists and comprised of both men and women, black and white, who pursued abolition in the years before the Civil War and sought to establish an egalitarian society post-emancipation. This group believed the keys to building an egalitarian society were securing colorblind citizenship and establishing biracial institutions, namely churches and schools.

The AMA spent hundreds of thousands of dollars planting churches in the postwar South and received the majority of Freedmen’s Bureau’s funds to build primary schools and universities in Washington DC, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Within these archives are thousands of letters written between the AMA’s home office in New York City and missionaries, teachers, military officers, and elected officials describing conditions across the postwar South and efforts to further the organization’s mission.

From this research “rabbit hole,” I’ve been able to gain a better understanding of the difficulties the AMA experienced in trying to achieve its goals, in particular, how the limited resources of the AMA, postwar violence, white supremacy, lack of powerful allies, and freed people’s own humble vision of postwar American society combined to limit the attainment of their lofty goals.

The first of their kind

ED: What strategies did black and white political activists employ to create a more equal society? PP: My first book project focuses on post-emancipation Washington DC. There, black and white political activists employed a variety of strategies to create a more egalitarian society including petitioning Congress, challenging discrimination through the court system, establishing communities for freed people, and building institutions such as First Congregational Church and Howard University, the capital’s first two intentionally interracial institutions:

PP: The study of American history reveals that although these principles were initially unequally applied, they have inspired successive generations of Americans who have pursued them to full inclusion within the body politic.

Personally, I have found inspiration in the leadership of President Abraham Lincoln. In his Gettysburg Address, he began by describing America as a nation “. . . conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” And yet the struggle to attain those principles had cost hundreds of thousands of lives and remained unfinished.

He concluded by calling upon those gathered to continue the work. “It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced . . . that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” At a time when America’s founding principles appear under unique threat, dedication to Lincoln’s goal of a government of, by, and for the people remains a noble pursuit.

ED: What’s one thing you wish that every student knew about American history?

PP: In a time when history is increasingly politicized and weaponized, I want my students to come away from my history courses with an understanding that American history should not be seen or used as a weapon, but rather as a vital resource.

History helps [students] understand the complexities of the past and prepares them for civic engagement by equipping them to become educated, responsible, engaged, and empathetic citizens.

ED: Thank you for your time and thoughtful insights, we will continue to follow your work!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Historian and Editorial Manager. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).